Most men with advanced prostate cancer initially respond well to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) and androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSI), but many develop resistance, often within two or three years from initial treatment. At that point, the disease is incurable.

“Castration-resistant prostate cancer is a major health burden, and as the population ages, prostate cancer deaths are increasing every year,” says Goutam Chakraborty, PhD, Assistant Professor of Urology, and Oncological Sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and a member of the Center of Excellence for Prostate Cancer at the Mount Sinai Tisch Cancer Institute.

Physicians have recognized the importance of ADT—and the challenge of resistance to it—for decades. “But it has been a mystery why some patients respond well to androgen therapy for many years, while others develop resistance,” Dr. Chakraborty says. Now, he and his colleagues have uncovered important clues during research funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Goutam Chakraborty, PhD, left, and Prathiksha Prabhakaraalva , PhD, in the Chakraborty Lab

The work, published in Cell Reports, outlined the complex role of the protein BCL2 in driving the transition from castration/hormone-sensitive to treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Their findings point toward new directions for delaying or preventing ADT resistance in advanced prostate cancer.

BCL2 Drives Resistance to Androgen Deprivation Therapy

BCL2 is a known player in a variety of cancers. It has been recognized for its antiapoptotic activity, preventing cancer cells from undergoing programmed cell death. More than two decades ago, researchers identified high levels of BCL2 in men with prostate cancer who did not respond to ADT. But early attempts to block the protein in prostate cancer patients failed. Then, in 2020, the Food and Drug Administration approved a BCL2 inhibitor, venetoclax, for blood cancers. Dr. Chakraborty and his colleagues thought it was time for a fresh look.

“The role of BCL2 in prostate cancer had never been clearly explained,” Dr. Chakraborty says. “Was the overexpression of BCL2 a cause or a consequence of drug resistance? It was a chicken-or-egg question.”

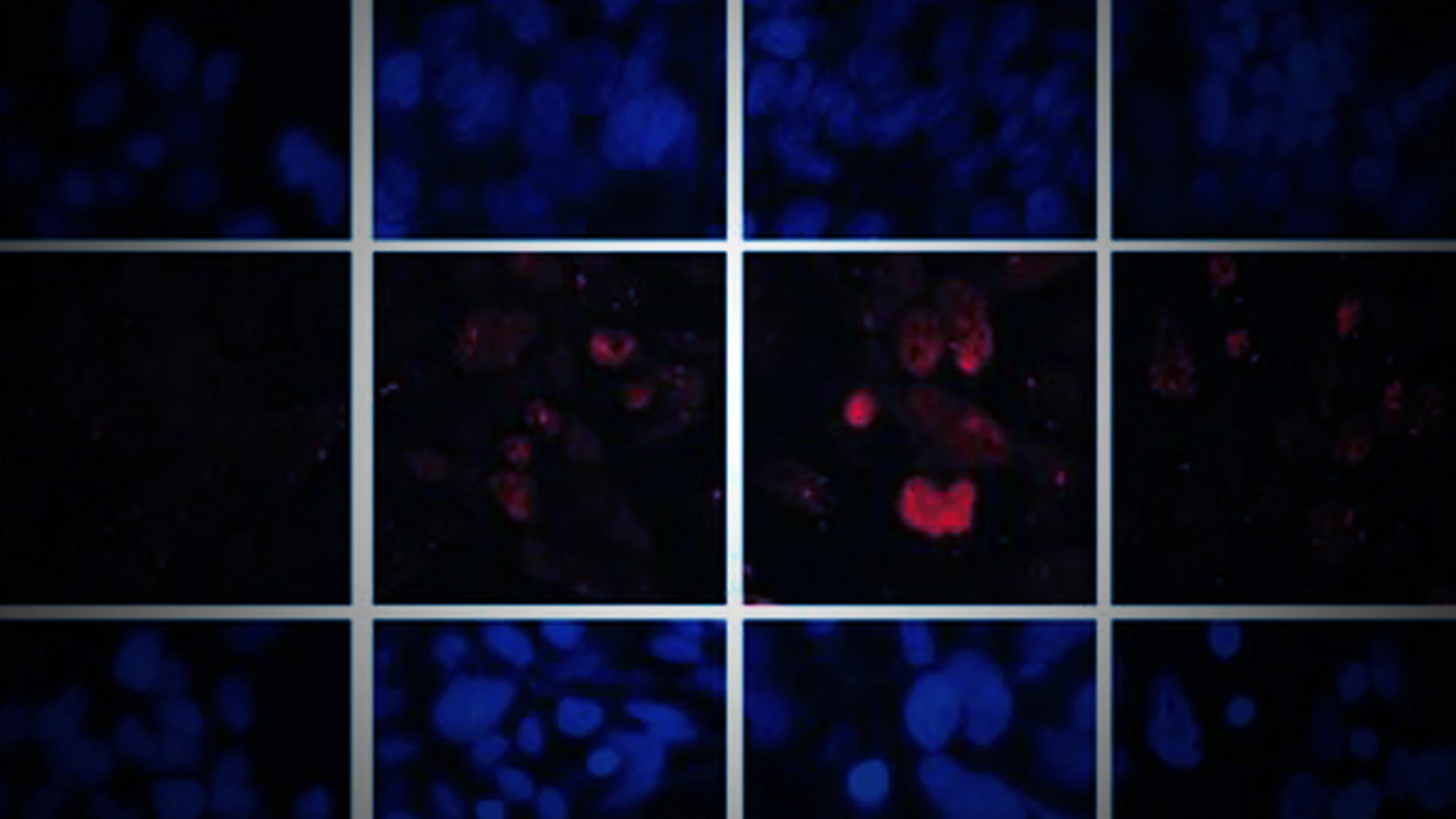

To answer it, researchers at the Chakraborty Lab turned to a combination of cell lines, patient-derived datasets, and mouse models to probe the role of BCL2 in early stage, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. They found an inverse relationship between BCL2 and androgen receptor activity: As androgen receptor activity is suppressed, BCL2 is upregulated. But the relationship was only present in the early life cycle of the cancer.

Unexpectedly, they found the role of BCL2 in prostate cancer was not only related to apoptosis. Instead, they discovered a complex feedback loop between BCL2, androgen signaling pathways, and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, which regulates cellular metabolism—specifically, lipid metabolism. “BCL2 was actually making the cancer cells more metabolically active, which makes them more aggressive and therapy resistant,” Dr. Chakraborty says.

Importantly, they found the feedback loop occurs in early stages of the disease, before the transition to castration resistance.

“Once the cells become castration resistant, ADT or ARSI does not induce BCL2,” Dr. Chakraborty says. “That’s why trials testing BCL2 inhibitors in castration-resistant prostate cancer were never successful. This interaction isn’t occurring in later stages of disease.”

But BCL2 may be implicated in other processes later in the disease course, the researchers found. In castration-resistant prostate cancer cells that overexpress BCL2, prolonged antiandrogen therapy increased cell plasticity and activated hedgehog signaling—both markers of aggressive disease, treatment resistance, and tumor cell plasticity.

“We started out thinking BCL2 was an antiapoptotic protein. But it seems to have other roles, including regulating cancer metabolism and driving early castration resistance—and, in later stages, regulating cell plasticity,” Dr. Chakraborty says.

Biomarkers and Clinical Trials: A New Focus on BCL2

With a new understanding of BCL2’s role, the team turned to venetoclax to inhibit it in castration-sensitive prostate cancer. In both cell lines and mouse models, the drug delayed the development of ADT resistance, particularly when combined with the androgen receptor signaling inhibitor enzalutamide. “When we combined the therapies, survival in mice almost doubled,” Dr. Chakraborty says.

In next steps, the team is pursuing a clinical trial to evaluate venetoclax or next-generation BCL2 inhibitors in patients with high BCL2 expression whose cancers are still sensitive to hormone therapy.

“Timing is critical. If patients have already stopped responding to antiandrogen therapy, this treatment is unlikely to be successful,” Dr. Chakraborty says. “But we hope that by giving the drug early, we can prevent the transition to castration resistance.”

In related work, the researchers are studying whether BCL2 might serve as an early biomarker for aggressive prostate cancer that is likely to evolve resistance to ADT, as well as a marker of cellular plasticity in advanced therapy-resistant disease. If so, high levels of BCL2 could indicate that a patient may benefit from more aggressive early therapy, for example, or identify which patients might benefit from more frequent monitoring after treatment to detect early recurrence.

In later stages of the disease, when BCL2 seems to be involved in cellular plasticity, BCL2 inhibitors might be beneficial alongside different treatments, such as PIK3-kinase inhibitors and hedgehog inhibitors. “BCL2 inhibitors may be useful in various stages of the cancer, but we’ll need to find the right drug combination for every stage,” Dr. Chakraborty says.

“We are still exploring the molecular mechanisms to understand BCL2’s role in these various signaling pathways,” Dr. Chakraborty says. “But if we can find new ways to prevent the transition to castration resistance, we could significantly affect the lives of people with prostate cancer.”