Mantu Gupta, MD, Professor of Urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Chair of Urology at Mount Sinai Morningside and Mount Sinai West, has known the answer to that question for years. Which is why he is leading the movement to set a new gold standard for the field through the use of flexible ureteroscopes untethered to wires, sheaths, and stents—and the severe discomfort they can cause patients.

“We shouldn’t keep doing things year after year just because that’s the way we were trained,” says Dr. Gupta, recognized globally for his advanced research and treatment of urinary stone disease. “We should constantly be looking for safer, less invasive ways to perform ureteroscopies that improve outcomes and minimize trauma and inflammation to the ureter for patients.”

Improvements in ureteroscopes made it possible for Dr. Gupta to transition to the new generation of flexible instruments while jettisoning guidewires, stents, sheaths, and even the standard use of fluoroscopy, which can pose serious health risks to physicians and other surgical suite personnel exposed to its ionizing radiation on a regular basis. While many of the new scopes are digital, Dr. Gupta opted for a fiber optic model with good visualization and a smaller tip (7.5 French) that fits into most ureters without the need for dilation.

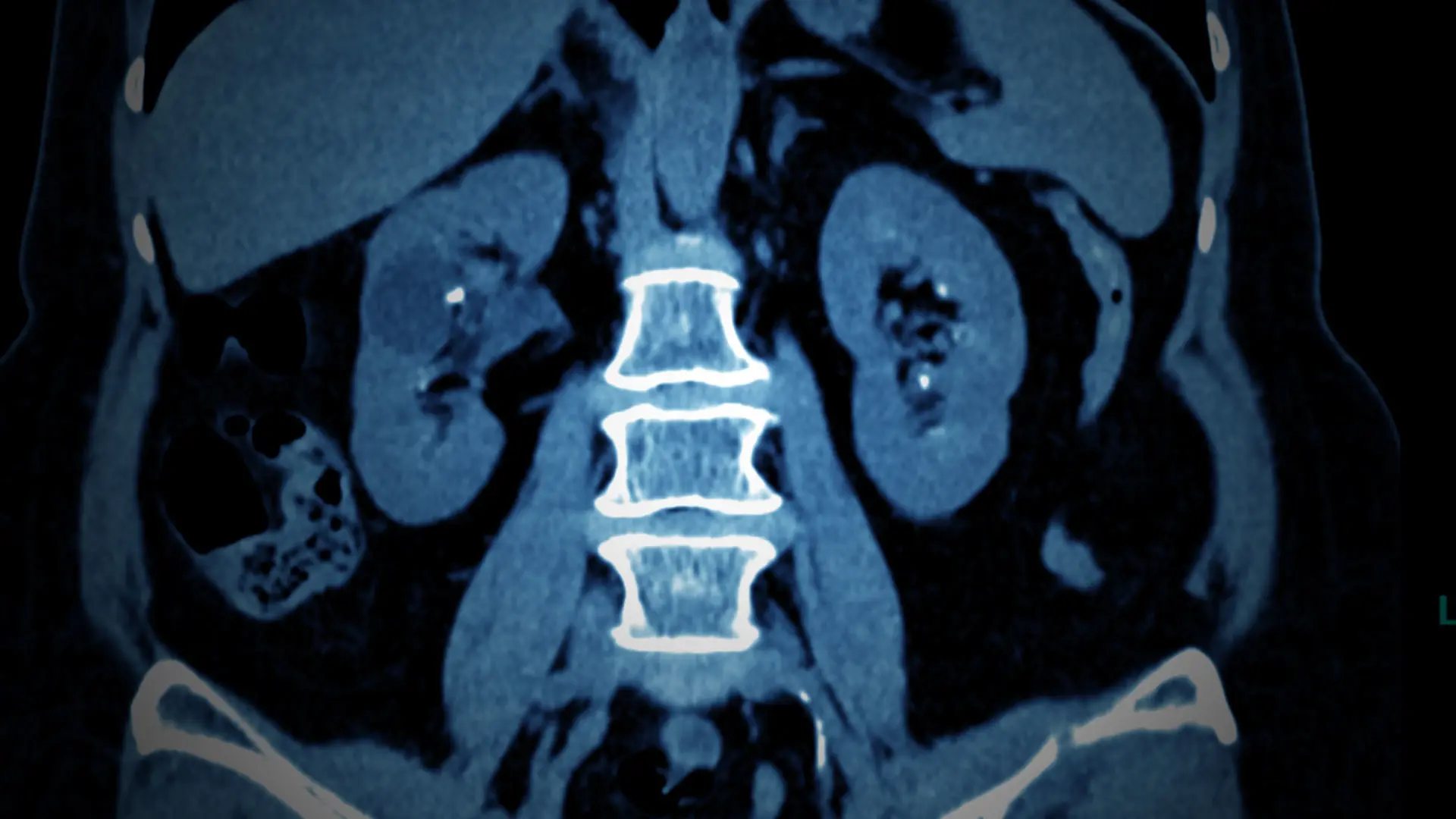

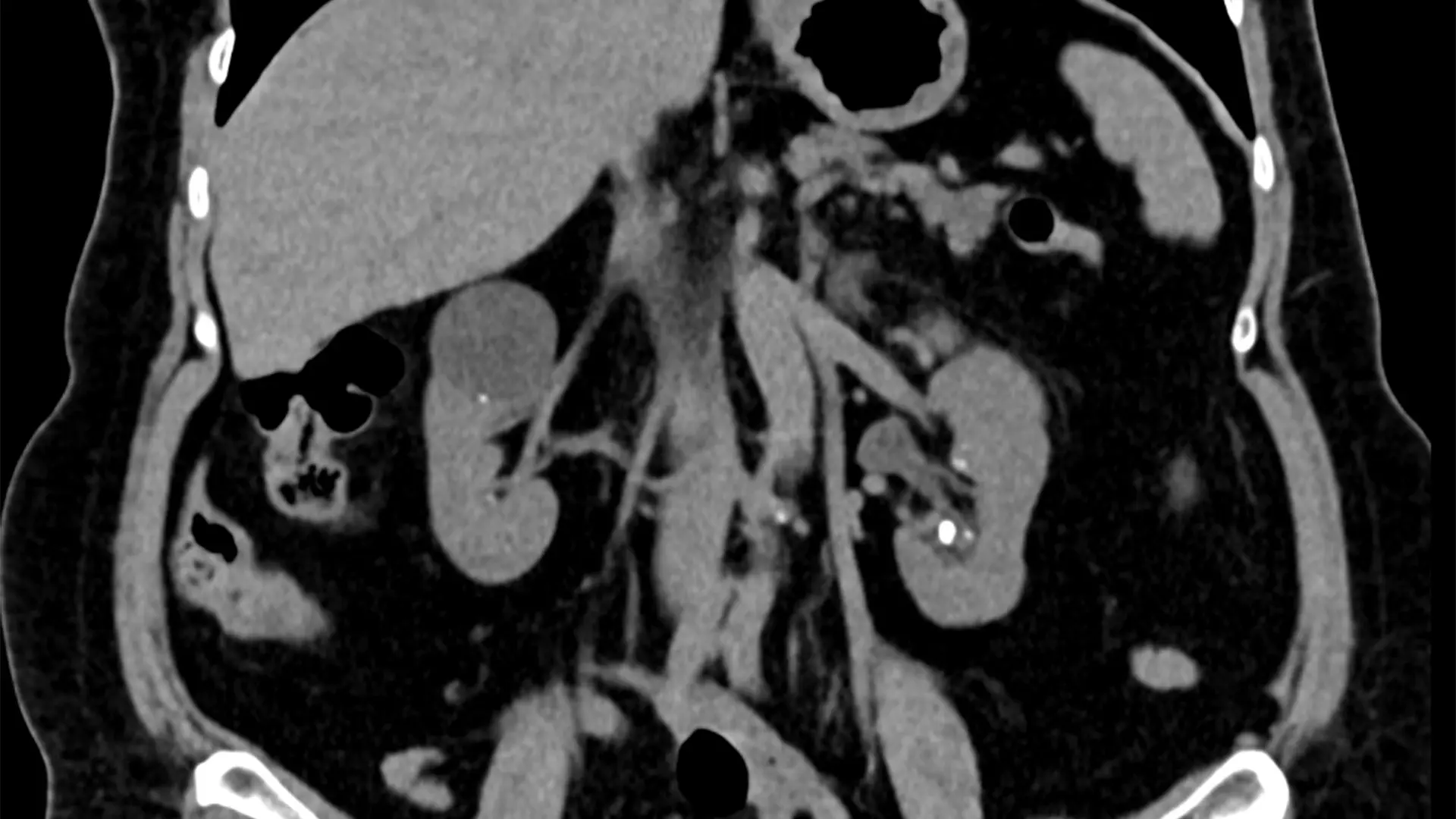

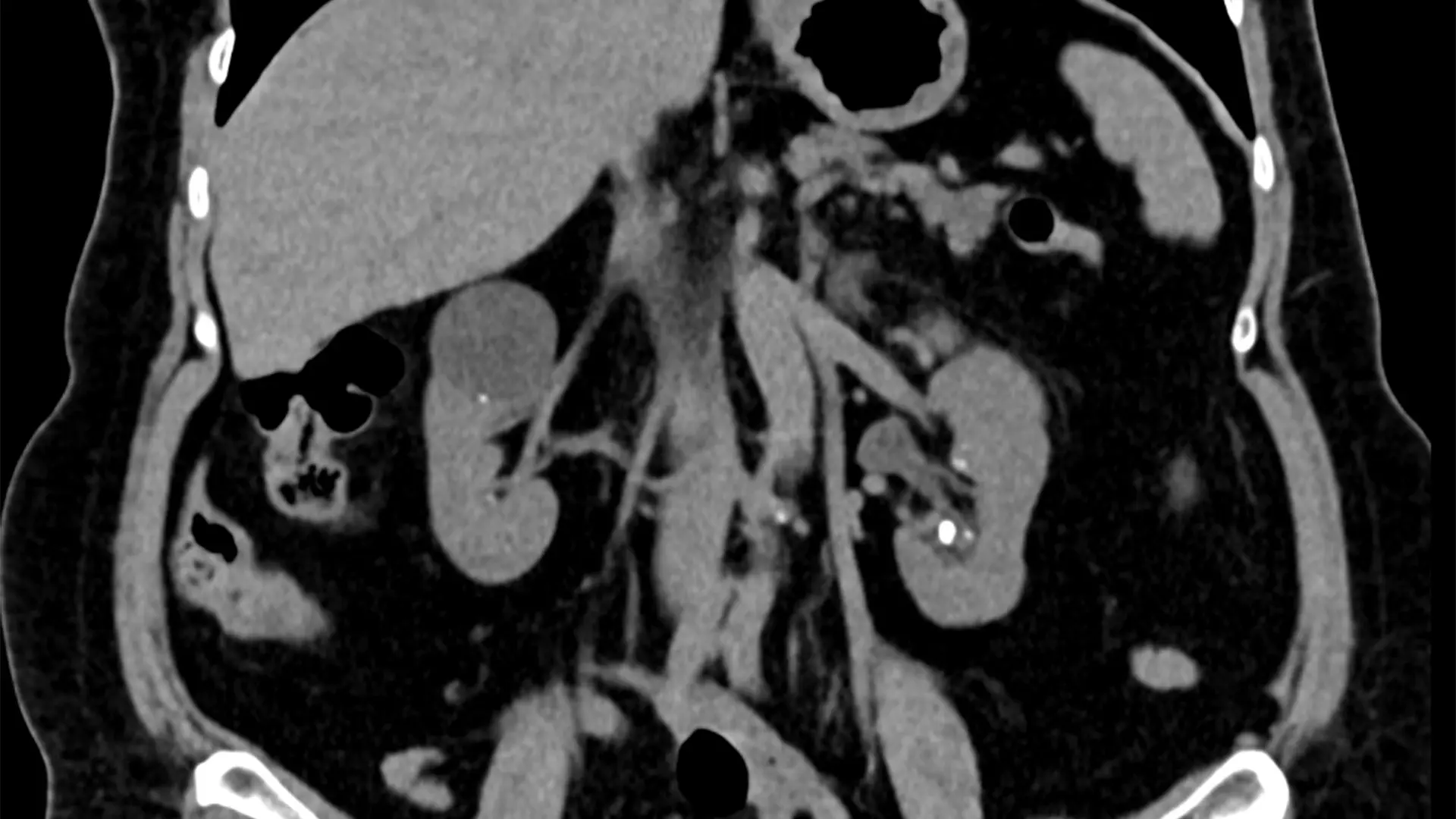

These are two images of a 70-year-old female with bilateral flank pain and more than 20 stones in each kidney was able to be treated with bilateral ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy without the use of guidewire, sheath, stent, or fluoroscopy with complete treatment of all stones.

“Because it has good rigidity and a very flexible tip it can be advanced more easily without the threat of breaking,” he says.

How do patients react to the stripped-down ureteroscopy procedure? “Those who have had kidney stones removed in the past have told me the new technique made a miraculous difference for them,” says Dr. Gupta, who is also Director of the Mount Sinai Kidney Stone Center.

The reasons are clear. Stents left in the ureter after surgery to ensure proper kidney drainage are particularly uncomfortable for patients, often leading to pain in the groin, bladder, and kidney areas, as well as frequent urgency and burning upon urination. “Some patients say the pain of the stent is worse than the pain of the stone,” says Dr. Gupta.

Insertion of guidewires can also cause distress to the ureter, especially in cases where the patient has a hematuria with an underlying malignancy. Nor are sheaths, which are typically wider than the ureter, patient-friendly since they can cause significant tears in the ureter, potentially leading to strictures and other complications.

If there is any downside to the new technique, also known as “no-touch,” it’s the learning curve required for its effective use by physicians.

Mantu Gupta, MD, Site Chair of Urology at Mount Sinai West and Mount Sinai Morningside, and Professor of Urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, is leading the movement to set a new gold standard for the field through the use of flexible ureteroscopes.

“The flexible ureteroscope is a long, thin, and relatively floppy instrument that deflects at the tip, so it takes a good amount of learning and practice to maneuver and twist it properly to get it into the ureter at the right angle without using a wire,” Dr. Gupta says. Nonetheless, he calls the procedure “perfectly teachable” and is confident the number of physicians routinely using it will grow significantly beyond the current handful once it gains traction in resident training programs, and once those urologists bring it into their private practices.

Forthcoming clinical studies on the safety and effectiveness of the technique, several of which Dr. Gupta has underway at Mount Sinai, will provide a springboard for accelerated growth, he firmly believes.

“Once urologists start to see the overwhelming advantages the procedure offers their patients, it will catch on across the country,” he says. “Another compelling reason is since we’re not using wires, stents, sheaths, and fluoroscopy, we’ll be eliminating a sizable cost to the health care system.”

A 70-year-old female with bilateral flank pain and more than 20 stones in each kidney was able to be treated with bilateral ureteroscopy and laser lithotripsy without the use of guidewire, sheath, stent, or fluoroscopy with complete treatment of all stones.

Here are two images of the renal stones.