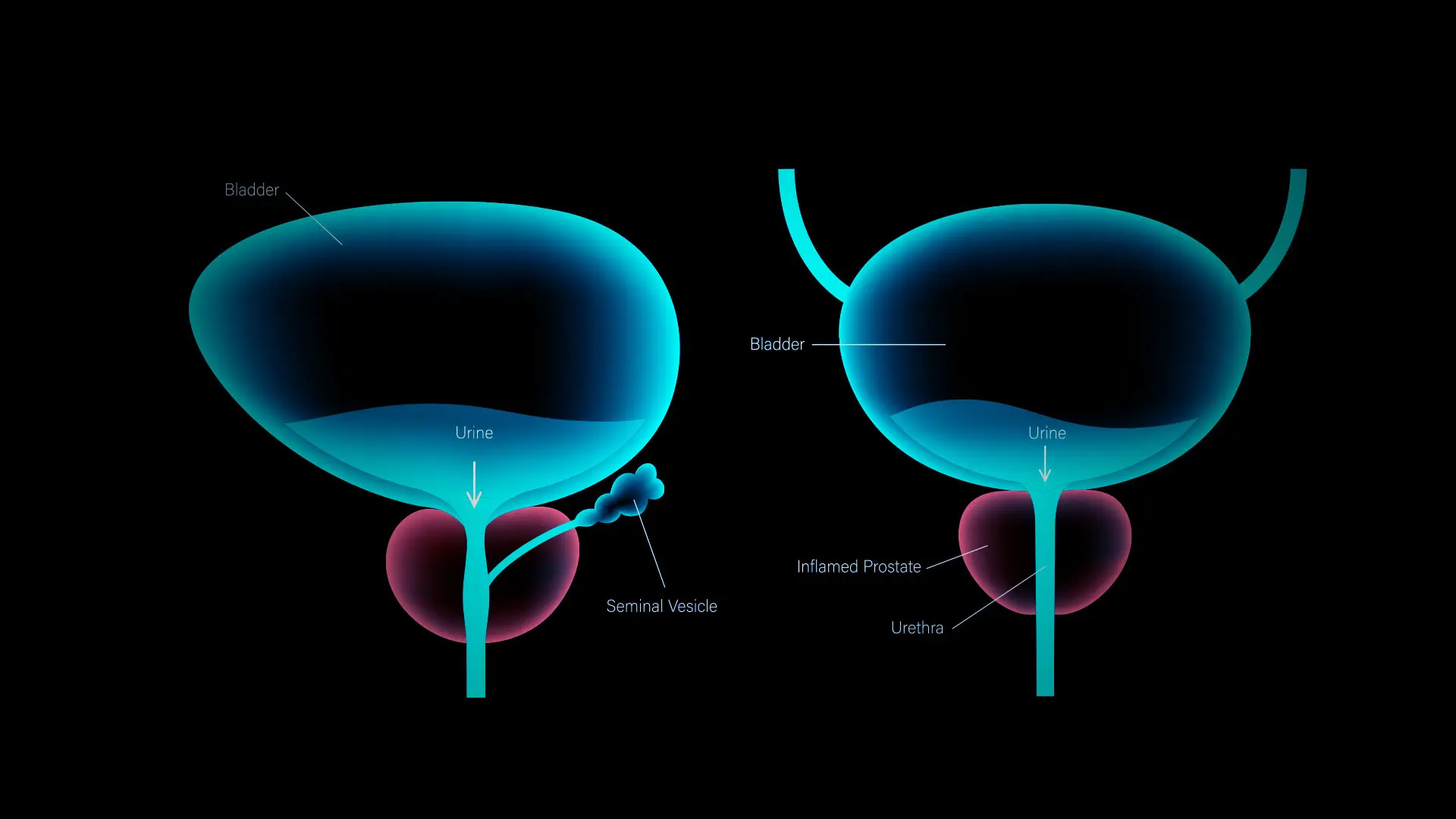

As the family of technologies for treating benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) continues to grow, the key to successful outcomes for male patients may well rest on a rather simple tenet: better diagnostic acumen.

That guidance from Steven Kaplan, MD, FACS, is being put to practical use by the Professor of Urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Director of the Men’s Wellness Program to determine which procedures—such as Aquablation® therapy, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), or prostatic urethral lift (PUL)—are most appropriate given the size and configuration of the problem prostate.

“The right diagnosis will make it much more likely that we choose the best therapy and therefore get not only a good result, but a durable one,” says Dr. Kaplan, who also serves as Chair of Research for the American Urological Association. “The problem is that as urologists we sometimes don’t listen closely enough to what our patients are telling us and jump to the conclusion that the problem is the prostate or overactive bladder when, in fact, it’s not.”

Steven Kaplan, MD, FACS, Professor of Urology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Director of the Men’s Wellness Program

A careful assessment that includes a medical history, physical examination, and, in some cases, invasive imaging can provide the evidence needed to select which type of surgery—or perhaps no surgery—is most suitable for a patient, he adds.

Dr. Kaplan is one of the leading users of Aquablation in the United States, a new technology that is proving to be a game changer in some practices by reducing the time it takes to treat BPH from 60 to 90 minutes to roughly eight minutes, with consistently good results. But even this advanced technology can fail, he explains, if the prostate is not judged to be of optimal size.

“We’ve found that if the prostate is too small, Aquablation may amount to overkill,” he says, “and that the technique is better suited to prostates that are too large for standard technologies such as TURP.”

As his caseload of Aquablation therapy approaches 175 patients to date, Dr. Kaplan acknowledges he is using the learning curve to modify and tweak the procedure. For example, if the prostate is too large—270 grams is the biggest he has treated—he may do some trimming of the organ prior to the procedure to ensure compatibility with the Aquablation instrumentation. Or he may partner with his colleagues in invasive radiology to shrink the prostate through embolization several weeks prior to surgery to make it more manageable for Aquablation therapy.

Mount Sinai was one of the first institutions to acquire Aquablation technology, and Dr. Kaplan ranks among its three most prolific users in the country. A minimally invasive procedure, Aquablation combines a camera, ultrasound imaging, and a computer-controlled, heat-free waterjet to enable efficient, precise removal of prostate tissue. Enhanced visualization through ultrasound allows for better targeting of areas that need treating, thus allowing for preservation of ejaculation and sexual function for patients, as well as for faster healing.

Dr. Kaplan is teaching the cutting-edge technique to residents and fellows, an effort that could expand to practitioners outside Mount Sinai as it continues to evolve as a center of excellence for the robot-assisted transurethral procedure.

“I’m using my own learning experience,” he says, “to instruct others and to improve Aquablation therapy to make it as safe and effective as possible for the growing numbers of patients who can clearly benefit from it.”