Developing a blueprint for tracheal transplantation has been three decades in the making. Ever since Eric M. Genden, MD, MHCA, FACS, lost a young patient with a large tracheal tumor as a medical student, he has made it his life’s work to someday give patients with nowhere to turn a viable option.

Dr. Genden, who is the Isidore Friesner Professor and Chair of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery for Mount Sinai Health System, has meticulously studied every failed attempt around the world. Small tracheal defects 5 cm or less in length could be repaired successfully. But when the surgeons tried to use reconstructive techniques—from plastic stents to stem cells—in long-segment defects, the procedure was fraught with complications and the outcome was often dire.

“Dating back one hundred years, extensive defects of the airway have been problematic. We saw this with diphtheria, polio, and now COVID-19. If you had a short segment you could cut it out and put it back together like a piece of pipe, but if you had a longer segment there was nothing you could do,” explains Dr. Genden.

Even though it was widely accepted throughout the field that tracheal transplantation simply was not possible, Dr. Genden refused to give up. He identified three key factors needed for a successful long-segment airway replacement. First, it had to be biologically integrated—rubber, plastic, or metal would never integrate into the tissue and would eventually lead to hemorrhage. Next, there needed to be functioning mucosa cilia inside the trachea to clean the lungs, so obstructions did not develop. Finally, the replacement had to be rigid enough to withstand the pressures of breathing or it would collapse.

“Nobody gave the trachea any respect—they thought it was just a tube. But all of the ways they tried to replace this tube ended with patients dying,” explains Dr. Genden. “In the end, we simply can't rebuild so much of what we are born with.”

Every one of the hundreds of articles he read identified the same roadblock: revascularizing the trachea. To address this, Dr. Genden—inspired by 19th-century anatomical drawings—began studying tracheal blood flow in animal models.

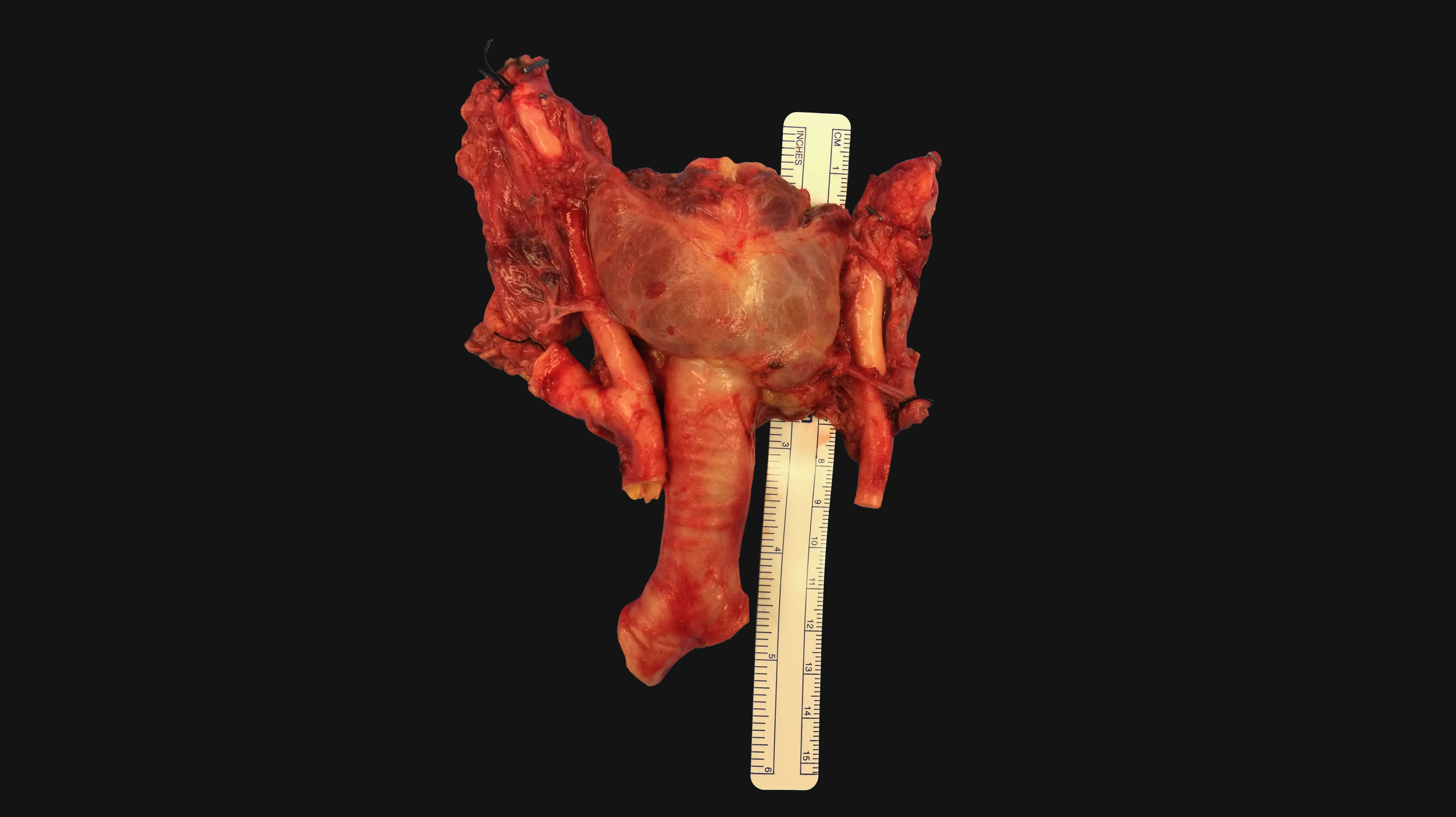

In 1990, with the support of a National Institutes of Health grant, Dr. Genden started a laboratory studying the immunology and biology of the trachea. The findings were transformative to his understanding of the procedure. Dr. Genden and his colleagues could get the trachea to survive, but since blood flows from the carotid arteries into the thyroid and then the trachea, the entire gland had to be transplanted too. They also found that the esophagus and trachea depended heavily on one another. If all of the organs were transplanted together, it might be just enough life support to keep the trachea alive.

Blood flow was only one piece of the puzzle. Dr. Genden also needed to understand the immunology behind the procedure. He began transplanting tiny tracheas into mouse models and studying the effects of immunosuppressants. He looked at what happened if the graft was rejected, died, or was put in backwards. Unlike other common transplants, such as the kidney or liver, the studies showed that the recipient’s own cells grew into the graft, so that it eventually became part of the subject.

As vascularized composite allografts (VCA) became widely accepted by state and federal authorities, a new doorway opened. Surgeons began transplanting multi-anatomic structures like the arm, voice box, or face.

Dr. Genden’s next step was to refine the technique in deceased donors. He tagged along with the transplant team, often in the middle of the night, to procure tracheas for study without intent to transplant.

Once he perfected the procedure, LiveOnNY, an organ and tissue bank serving the greater New York City area, agreed to transfer a donor to Mount Sinai when the time was right.

With only a half-day of notice, Mount Sinai mobilized an entire team ready to conduct a historic operation.

Featured

Eric M. Genden, MD, MHA, FACS

Professor and Chair of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery