Why can’t a tracheal transplant occur? Renowned otolaryngologist Eric M. Genden, MD, MHCA, FACS, had pondered that question since his days as a medical student.

For the past 30 years, Dr. Genden has searched for the answer—scouring the literature, rejecting scientific dogma, and gathering his own evidence about what goes wrong when surgeons try to replace and rebuild this notoriously tricky organ.

Without transplantation, patients with long-segment tracheal disease have either died or been forced to breathe through a hole in their neck. That changed on Wednesday, January 13, 2021, when a team of surgeons led by Dr. Genden conducted the first successful human tracheal transplant surgery. More than 50 specialists were involved in the historic operation, in which the team spent 18 hours harvesting trachea from a donor and then implanting it into the patient.

“This development will forever change the standard of care for organ transplantation. For the first time, we are able to offer a viable treatment option to patients with life-compromising long-segment tracheal defects,” explains Dr. Genden, who is the Isidore Friesner Professor and Chair of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery for Mount Sinai Health System and Professor of Neurosurgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “It is particularly timely that we were successful now given the growing number of patients with extensive tracheal damage following COVID-19 complications.”

The Process: Breathing Life Back Into the Trachea

There was no guide for tracheal transplantation. Surgeons had long thought that the complexity of the organ made it impossible to revascularize. However, based on years of anatomical studies, Dr. Genden was able to develop a reliable, reproducible, and technically straightforward blood flow protocol that utilized adjoining organs, structures, and blood vessels.

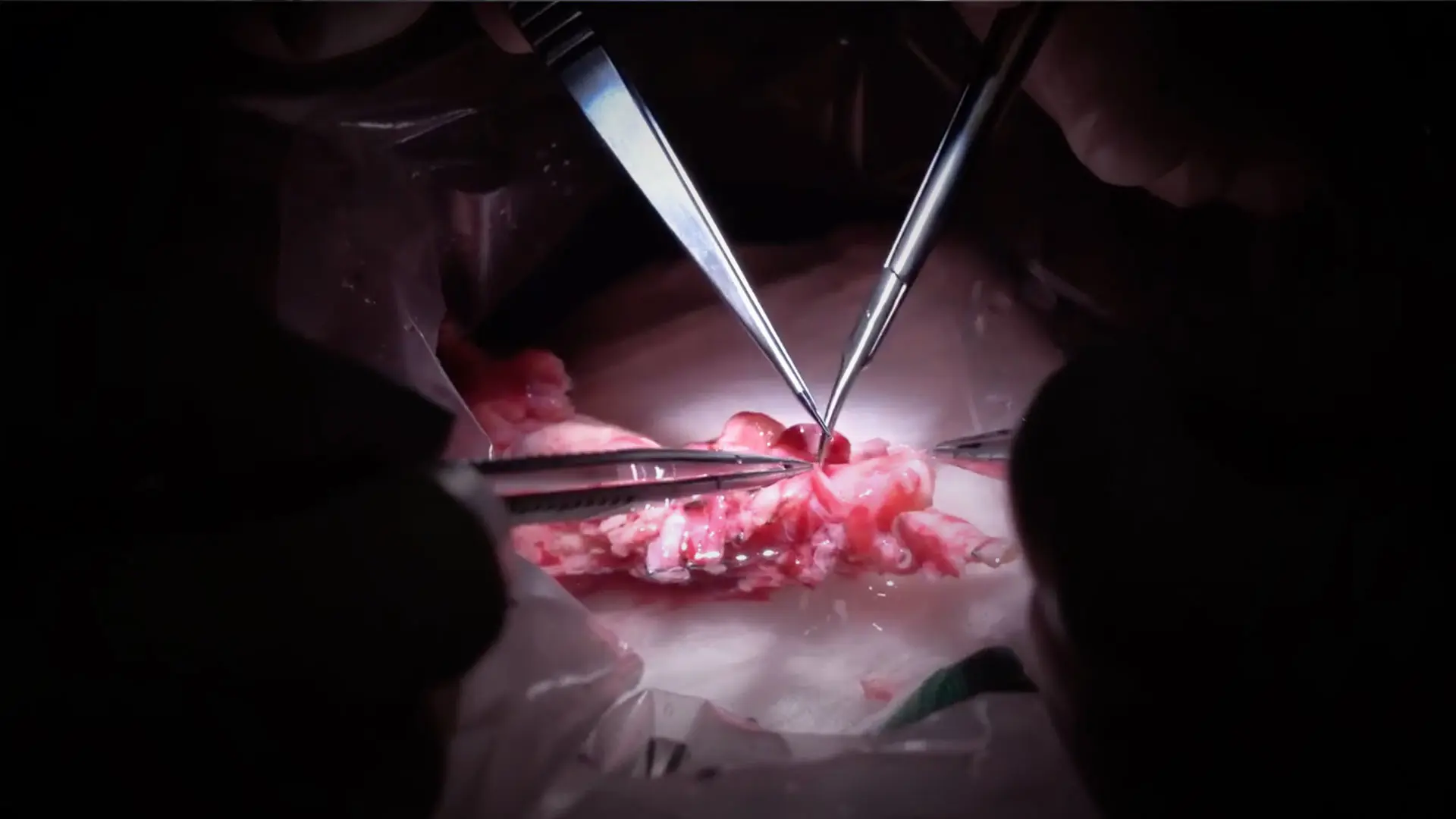

When the team dissected the donor, they took the full length of the trachea all the way from the cricoid cartilage down to the carina where it separates into the lungs. But the key to their success was bringing the entire thyroid, including both the superior and inferior thyroid vessels, as well as the esophagus and associated feeding arteries along with it. After the patient’s diseased trachea was resected, surgeons transplanted the donated system of organs.

The allograft vessels were dissected and prepared on a side table with a microscope. Then, using a series of microvascular anastomoses, they connected the small blood vessels that nourish the donor trachea with the recipient’s blood vessels. When the allograft was placed, it released the blood vessels and the new structure began to bleed, showing that the trachea was still very much alive.

“Seventy years of dictum went out the window the moment we saw the graft come alive. We proved that you can revascularize the trachea and breathe life back into it,” says Dr. Genden.

To reduce risks like hemorrhage and infection, the team had to work effectively and efficiently. “We had no guide for how well the graft would tolerate transplantation, so we worked very quickly,” describes Dr. Genden. “Ultimately, everything went smoothly because we assembled a strong team with extensive surgical expertise in organ transplantation and tracheal reconstruction.”

After thirty years of extensive research, Dr. Genden successfully conducted a procedure thought to be impossible. However, he contends that the best part was the patient’s reaction.

“This courageous woman who had been breathing through a tracheostomy was elated. She is now at home—smiling, laughing, and walking around for the first time in six years.”

The Immunology: Identifying a New Protocol

Knowing that organ rejection was a major risk, identifying a pre- and post-operative recipe for success was crucial. Dr. Genden drew upon Mount Sinai’s expertise with more than 10,000 transplant procedures to develop a brand-new immunology protocol that would work best for the recipient.

Prior to surgery, the patient was inducted with antithymocyte globulin. After the procedure, she remained intubated for six days and was treated with triple-therapy immunosuppression, which included tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and corticosteroids.

“The trachea has a lot of similarity to the intestines; they are hollow structures lined by mucus-producing epithelium that are very immunogenic,” explains Sander S. Florman, MD, the Charles Miller, MD Professor of Surgery and Director of the Recanati/Miller Transplantation Institute. “Based on this understanding, we came up with what we thought would be an appropriate immunosuppressive regimen.”

The Follow-Up: Monitoring the Healthy Graft

Narrow-band imaging and bronchoscopic biopsies were used regularly to monitor the graft. The recipient continued to show mucosal vascularization consistent with a healthy and well-perfused allograft, as well as viable epithelial lining with basal cell differentiation of ciliated epithelium.

Decades of science and experimentation laid the foundation for this surgical achievement. But paramount to its success was the long history of expertise in transplantation and spirit of collaboration that exists at Mount Sinai.

Dr. Genden is thankful for the role everyone played in this milestone. In particular, he acknowledges Samuel DeMaria, Jr., MD, Professor of Anesthesiology, Pain, and Perioperative Medicine; and Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, who was the procedure anesthesiologist; the entire Transplant Intensive Care Unit, who took care of a patient they had never seen before; Mount Sinai’s leadership; Dr. Florman, who trusted him to perform the procedure; and Amy Friedman, MD, Chief Medical Officer of LiveOn New York, who helped procure the donor.

“There are only a few centers around the world that have the depth and ability to do this. At Mount Sinai we have a long history of pushing the limits, being innovative, and helping patients who may not have an opportunity elsewhere,” added Dr. Florman. “Credit to Dr. Genden for having the conviction and determination to see his 30-year vision through from an animal model to the lab and finally a person. This extraordinary effort was the result of his vision, skills, and perseverance—as well as the strength and trust of this incredible patient.”

Featured

Eric M. Genden, MD, FACS

Professor and Chair Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery

Sander S. Florman, MD

Director Recanati/Miller Transplantation Institute