For years, the p53 protein has been investigated by laboratories around the world for its well-characterized tumor suppression activity in human cancer, revealing a host of unanswered questions around the biology and molecular mechanisms underlying mutant p53 and how they promote various forms of cancer. A new study led by Mount Sinai and other prominent institutions with expertise in oncology is taking a much different approach than past efforts, one that could finally unravel some of the fundamental mysteries around the oncogenic activity of p53 and the TP53 gene that encodes it.

“Many labs have done different experiments around p53, each focused on one mutation,” says James Manfredi, PhD, Professor of Oncological Sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and one of the leaders of the study. “What we’re doing is bringing together a multidisciplinary team of experts who study p53 from different perspectives to look at a large number of different mutations, and we’re doing it with a breadth and depth not previously possible."

James Manfredi, PhD, Professor of Oncological Sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, is one of the leaders of the study examining p53 mutation from a multidisciplinary approach, leveraging expertise spanning genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, functional genomics, organismal biology, and clinical oncology.

“We expect this seminal research to produce novel new insights into the behavior of p53 mutant cancers and identify allele-specific mechanisms for developing important new therapies,” adds Dr. Manfredi. “Through this work, we hope to finally bring some clarity where confusion has prevailed.”

A Collaborative Effort

The study, powered by a National Institutes of Health grant awarded in August 2025, consists of four separate projects led by scientists from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Institute, Columbia University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the Mount Sinai Tisch Cancer Center. The teams—with expertise spanning genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, functional genomics, organismal biology, and clinical oncology—coordinate on research, building on output from each other through a core capability known as the Epigenomics Shared Research Core. This Mount Sinai-managed Core provides sequencing and bioinformatics support to facilitate the generation and interpretation of large data sets. The specialized expertise of the Core ensures each project is using the most state-of-the-art approaches to generate and interpret its data.

Researchers from each project have agreed to focus on two types of cancer: pancreatic cancer and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. “We drew some early criticism for trying to tackle too many cancer types,” acknowledges Dr. Manfredi, “so we narrowed it down to two cancers that exhibit very high mutation rates.” Within that construct, the teams are using the same mouse models and human cell lines to elucidate the mechanisms that allow tumor-derived mutant p53 proteins to enhance cancer invasion and metastasis. The four projects are:

Project 1, under the direction of Scott Lowe, PhD, Chair of Cancer Biology and the Genomics Program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; and Francisco Sánchez-Rivera, PhD, Assistant Professor of Biology at the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT, is performing high-throughput cellular and molecular phenotyping of mutant TP53 alleles to determine their variation.

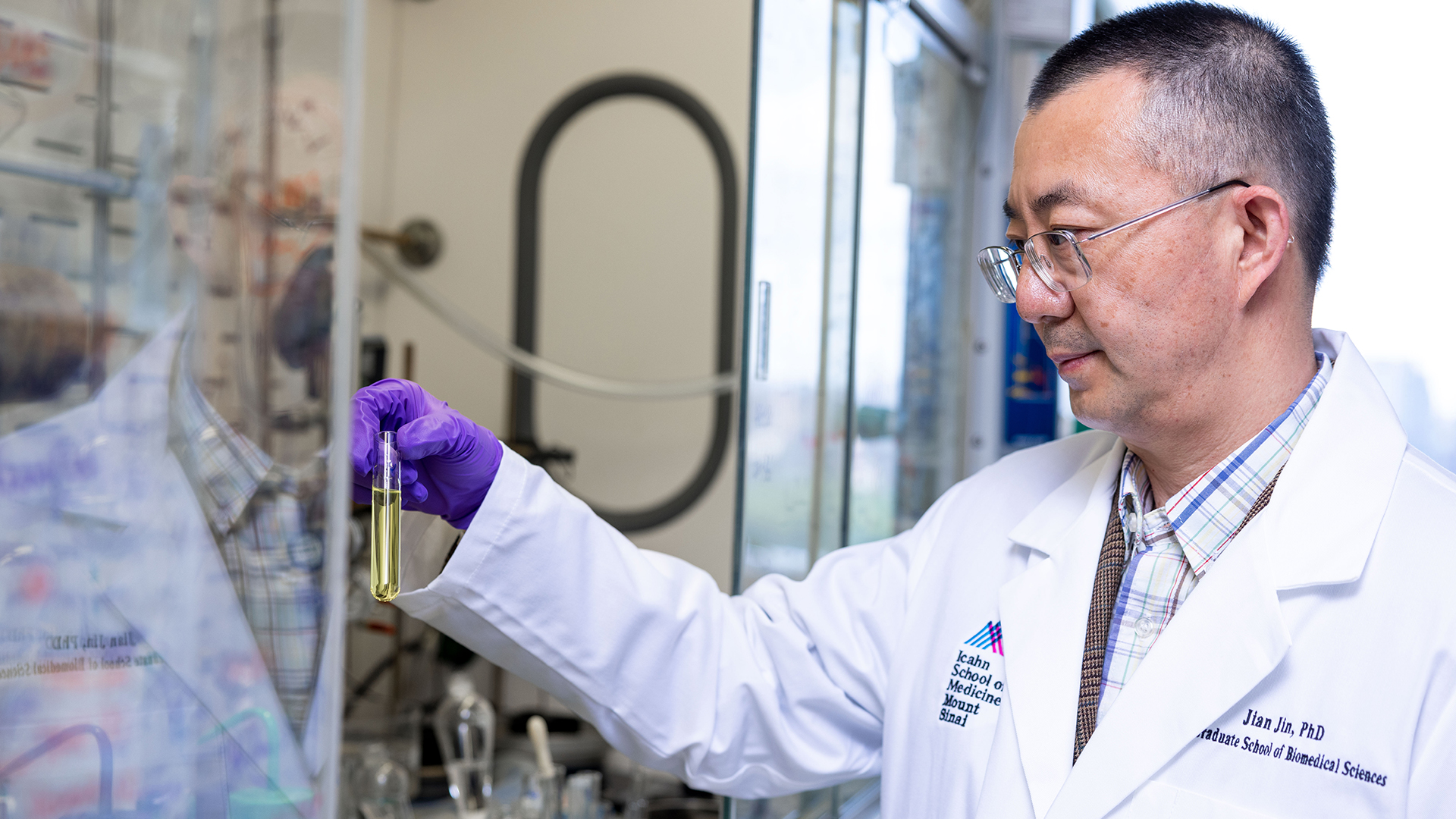

Project 2, led by Wei Gu, PhD, Professor of Pathology and Cell Biology at Columbia University; and Jian Jin, PhD, Director of the Mount Sinai Center for Therapeutic Discovery, is investigating BACH1 as a novel interacting protein and key mediator of a tumor-derived p53 mutation known as 175H, which is present in 5 percent of all tumors.

Project 3, led by Anil Rustgi, PhD, Director of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center at Columbia University; and Carol Prives, PhD, Professor of Biology at Columbia, is working to define the biological roles of mutant p53 and Mdm2, a protein that acts as a negative regulator and potent inhibitor of p53, in promoting cancer invasion and metastasis.

Project 4, led by Dr. Manfredi and team co-leader Emily Bernstein, PhD, Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Oncological Sciences at Mount Sinai, is focused on the role of p53 as a transcription factor in determining cell fate decisions and their impact on tumor suppression in vivo. Dr. Manfredi’s laboratory was among the first to perform detailed p53 studies around epigenomics in vivo and to provide fresh insights into the basis of tissue-specific radiosensitivity. Dr. Bernstein’s research has deciphered the underlying mechanisms of chromatin in cancer. She also heads up the Epigenomics Shared Research Core that provides cutting-edge technology and analyses of the extremely large data sets to be generated by each project.

Understanding TP53 And Mutant p53

TP53 mutation is a key distinguishing feature of tumor cells, but the mechanisms by which potential pro-oncologic “gain-of-function” mutations impact cancer progression remain enigmatic, notes Dr. Manfredi. “We believe our multimodal and systemic approach can now build on past research by these teams to produce critical new information and therapeutic approaches that will be relevant across many cancer types,” he says.

Mutation of the TP53 cancer suppressor gene occurs in more than half of all cancers and poses significant challenges. The p53 protein is a transcription factor that binds in a sequence-specific manner to the DNA of cells and activates or represses target genes to maintain genomic stability. Scientists know that a mutated TP53 gene loses its binding ability and thus impairs to varying degrees the tumor suppressor function of p53. This phenomenon is also known as “loss-of-function,” resulting in uncontrolled growth, division, and spread of cancerous cells.

TP53 gene mutation occurs in more than half of all cancer types.

Researchers have often focused on loss-of-function events of the tumor suppression gene.

The Mount Sinai multi-institutional study presents a unique angle: gain-of-function.

Understanding gain-of-function is a step toward viable targets for intervention.

While laboratories over the years have been largely focused on loss-of-function events in tumorigenesis, emerging research has suggested that mutant p53 proteins may also have acquired gain-of-function activities. These include inducing resistance to cancer drugs, promoting metastasis, and inhibiting apoptosis of cancer cells.

Focusing on p53’s gain-of-function traits holds enormous potential for scientific breakthroughs, beginning with cancer diagnosis and, eventually, treatment. “It’s pretty easy nowadays to drug an oncogene, but loss-of-function raises the difficult question: what exactly do you drug?” says Dr. Manfredi. “What we find so exciting about gain-of-function is that suddenly you have a viable target for intervention. If we as scientists can first understand how the mutant p53 is gaining this metastatic ability, we could potentially develop a drug to block or inhibit it.”

The multi-institution p53 study is specifically designed to tackle some of the fundamental issues and questions surrounding gain-of-function. Those include providing proof of principle that the activity even exists and, if so, how to categorize the mutants as either gain-of-function or loss-of-function. The team expects to have preliminary results within the year, offering fresh insights on the mechanism of action of specific mutants, setting the stage for large-scale screening to allow for their classification, with implications for patient prognosis.

“At the very least, we could make great strides in prognosis because we could now advise clinicians to check the p53 mutation of the tumor,” says Dr. Manfredi. “And if its gene signature indicates gain-of-function, it will probably require more aggressive treatment. If it involves loss-of-function, however, the treatment and outcome are going to be much different. Either way, the implications for patients are huge.”

Featured

James Manfredi, PhD

Professor of Oncological Sciences at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai