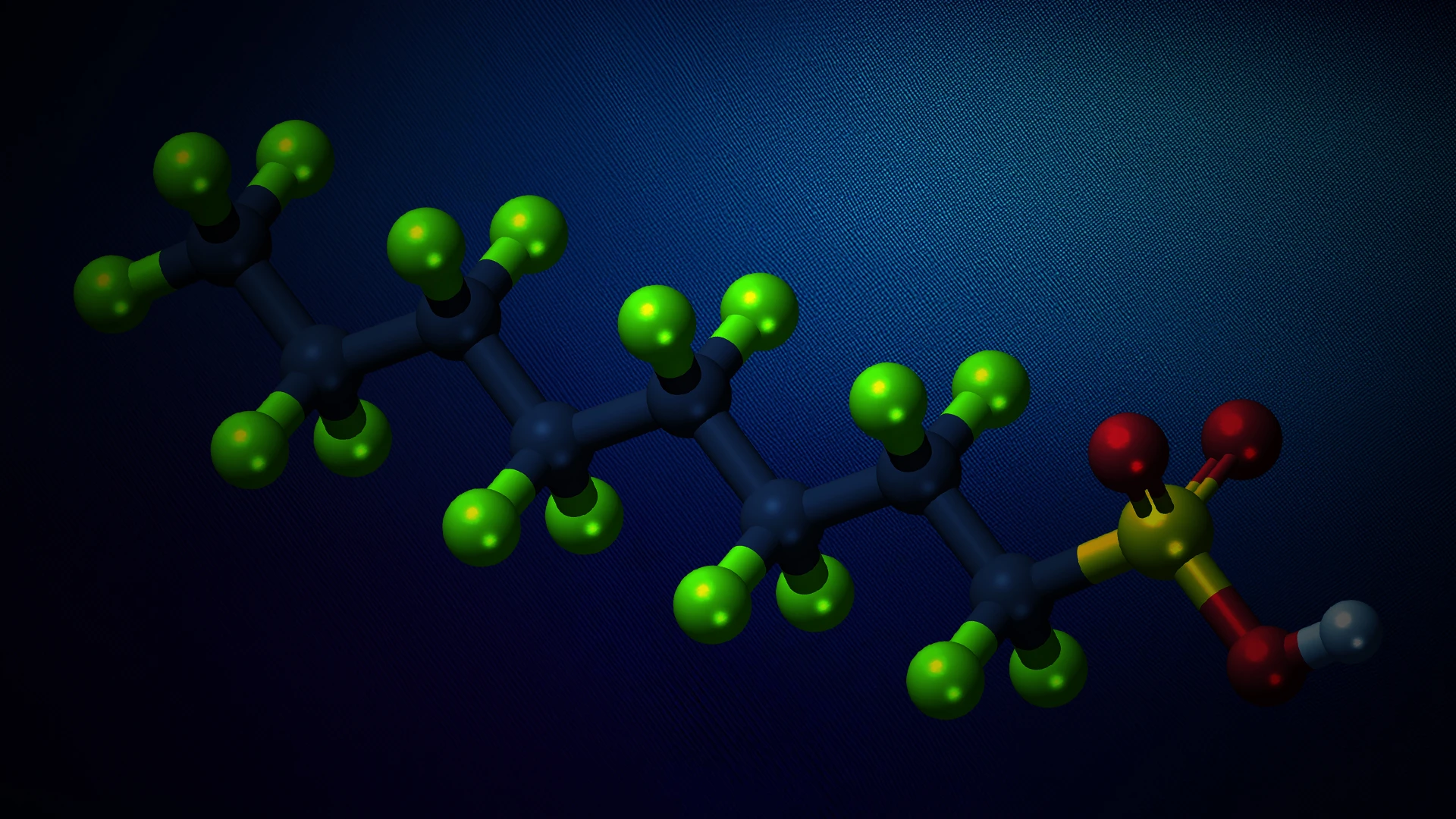

Work from a multidisciplinary group of Mount Sinai researchers is adding evidence to the conjecture that exposure to ubiquitous endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), such as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), can contribute to cancer risk. PFAS—found in everyday products such as nonstick cookware, clothing fabric, and plastic bottles—have been dubbed “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down easily and are found in soil, air, and water.

The research team was led by cancer epidemiologist Maaike van Gerwen, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, and exposome chemist Lauren Petrick, PhD, Professor of Environmental Medicine and Climate Science. Other team members included a thyroid cancer surgeon and a biostatistician.

While thyroid cancer diagnoses over the past decades have increased due to increased detection with imaging, that alone does not tell the whole story, says Maaike van Gerwen, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology (Head and Neck Surgery). Her team has found evidence that exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances might have led to increased cancer risk.

“We have a full spectrum of people who put their heads together, each coming from their own expertise to look at this very challenging area of research,” says Dr. van Gerwen.

Findings from their work were published in eBioMedicine in October 2023 and received a Team Science Award from the Institute for Translational Sciences (ConduITS) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Thyroid Cancer and PFAS Links

In the United States, thyroid cancer incidence increased by about 3.6 percent per year between 1974 and 2013. In 2024, there were an estimated 44,020 new cases of thyroid cancer and about 2,170 thyroid cancer deaths. Both were higher in women than men.

The increase in thyroid cancer diagnoses is partly due to increased detection with imaging, but not entirely. Other forces are likely at work, since the increases have been seen in younger people who don’t routinely undergo imaging, and, in some cases, the cancer is detected at advanced stages. If increased detection were the sole factor, the increase would mainly be of small tumors, Dr. van Gerwen notes.

Known risk factors for thyroid cancer include obesity and exposure to ionizing radiation. But recently, exposure PFAS have been increasingly recognized as health threats.

“The products work really well. It’s just that we figured out they’re not good for our health. Some were phased out beginning in the early 2000s, but those were replaced with new ones. There are thousands of different PFAS chemicals still in use, and we’re just beginning to try to understand their health effects,” Dr. van Gerwen says.

The study found that, in particular, for the PFAS called perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (n-PFOS), there was a 56 percent increase in the rate of thyroid cancer diagnosis per doubling of n-PFOS intensity, seen in the above data.

The study compared 88 people with thyroid cancer and 88 matched controls from a medical record-linked biobank housed at Mount Sinai. There was a significant rate increase (p=0.009) of 56 percent of thyroid cancer diagnosis with each doubling of a specific PFAS called perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (n-PFOS). Significant associations were also found for other PFAS.

Future Plans

The team is now moving forward with funding from the National Institutes of Health, Mount Sinai, and other sources to repeat this study in a much larger group of participants in the United States and Europe.

This work will include examining metabolic pathways in thyroid cancer to see if there are differences from healthy controls and to examine correlations with blood PFAS levels, as measured by liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry.

“Some of our team members developed methods to look at these metabolites in blood and see if there are peaks in certain metabolites of certain pathways. Then, we try to see if there's a link with these PFAS levels that we also found in blood. If we can identify pathways that link PFAS to cancer, we ultimately hope to identify these patients earlier and potentially intervene,” Dr. van Gerwen explains.

Another of the team’s projects involves collaboration with the Department of Defense (DoD) to examine PFAS in military personnel, since they have high occupational exposure to PFAS-containing chemicals, such as firefighting foam. The DoD considers such work high priority, she notes.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the European Union have also identified PFAS exposure as a potential health crisis. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) now recommends PFAS testing followed by thyroid function testing in patients with high PFAS exposure.

Until more data are available, Dr. van Gerwen advises that clinicians ask patients what they do for a living, to help determine if they might have higher-than-average PFAS exposure. “I think it would be great if clinicians can ask a little bit more about what people do in life. We know, for instance, that firefighters have a higher risk of thyroid cancer. This is potentially very valuable information, because if I know someone has a higher risk, I might be a bit more cautious in treating them.”

Featured

Maaike van Gerwen, MD, PhD

Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery

Lauren Petrick, PhD

Professor of Environmental Medicine and Climate Science