Global function metrics such as the Glasgow Outcome Scale - Extended are the gold standard for classifying clinical trial outcomes among patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). However, the resulting classifications are oversimplistic, failing to account for heterogenous long-term outcomes observed among these patients. Mount Sinai researchers have partnered with other institutions to address this challenge through a new study that identifies TBI phenotypes.

Published online in Brain Communications in June 2025, the study developed and validated four distinct phenotypes among a well-characterized cohort of individuals with chronic TBI, says Raj Kumar, PhD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Rehabilitation and Human Performance, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“The prevailing wisdom among clinicians has been that if you have seen one brain injury, you have seen one brain injury. Each patient is unique and we cannot assume every patient follows the same linear course of recovery,” says Dr. Kumar. While there is data to support that brain injuries are heterogenous and distinct, there hasn’t been a systematic way toward that approach.

Raj Kumar, PhD, MPH, Assistant Professor, Rehabilitation and Human Performance, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, is devising a new way to classify brain injury based on clustered phenotypes. Although physicians and researchers believe that brain injuries are heterogenous and distinct, there hasn't been a systematic way to back that approach; Dr. Kumar's study adds evidence to this method.

“Our clustered phenotypes capture the full spectrum of recovery: while we recognize each patient’s recovery path is unique, patterns of similarity do emerge when you look at large datasets, and distinct subgroups can serve as a useful starting point for interventions,” he says.

A Comprehensive, Multimodal Study

The prospective study enrolled participants from the Late Effects of Traumatic Brain Injury (LETBI) study, a multicenter initiative for identifying the clinical signatures of TBI pathology. The LETBI study follows patients older than age 18 with varying forms of TBI—including chronic, complicated, and mild to severe—all the way to autopsy. LETBI participants undergo extensive neuropsychological, physical, motor, and mood tests and self-reported assessments spanning more than clinical measures, in addition to neuroimaging.

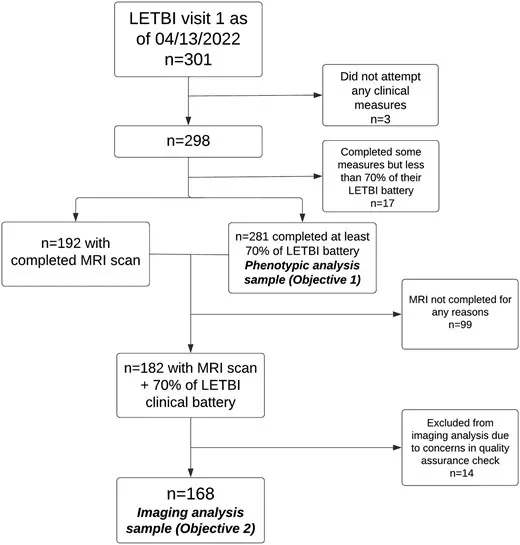

For the phenotype study, Dr. Kumar and the research team enrolled 281 LETBI participants who had completed at least 70 percent of their clinical assessment. Using unsupervised machine learning, the team performed a 70-30 split of training (n = 195) and validation (n = 86) to identify clusters of individuals with similar profiles or symptoms.

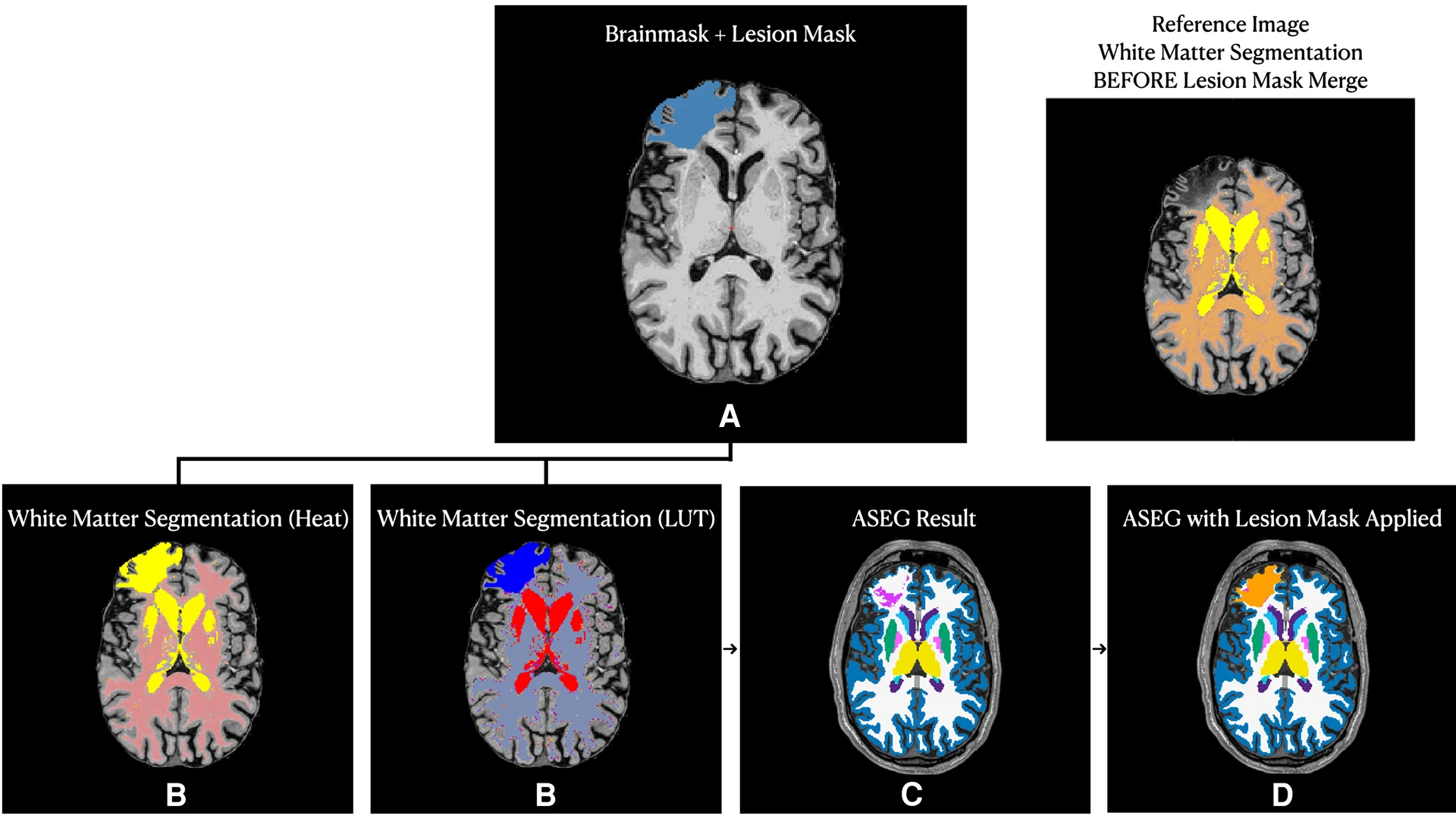

A schematic of the phenotype study, which enrolled participants from the Late Effects of Traumatic Brain Injury (LETBI) study.

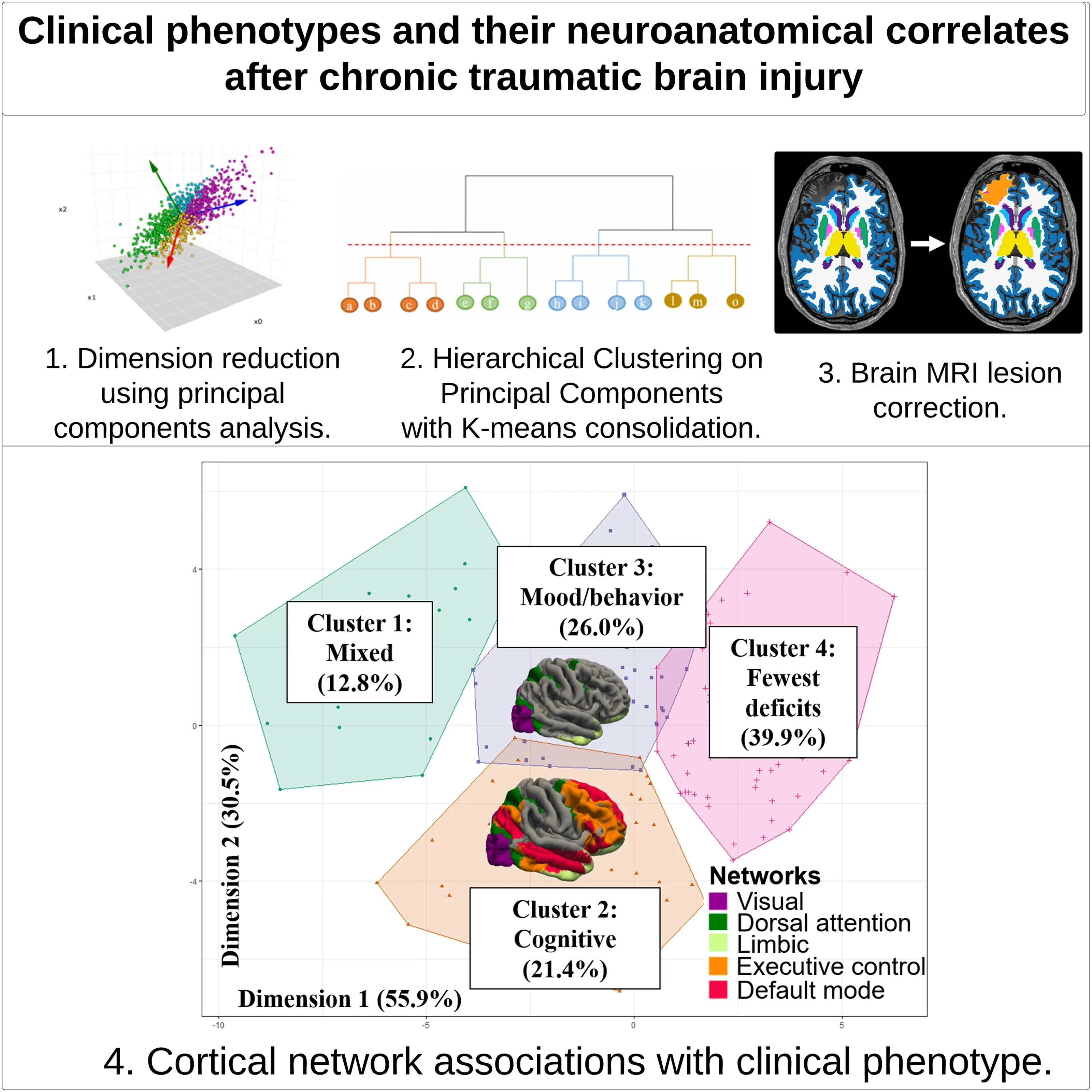

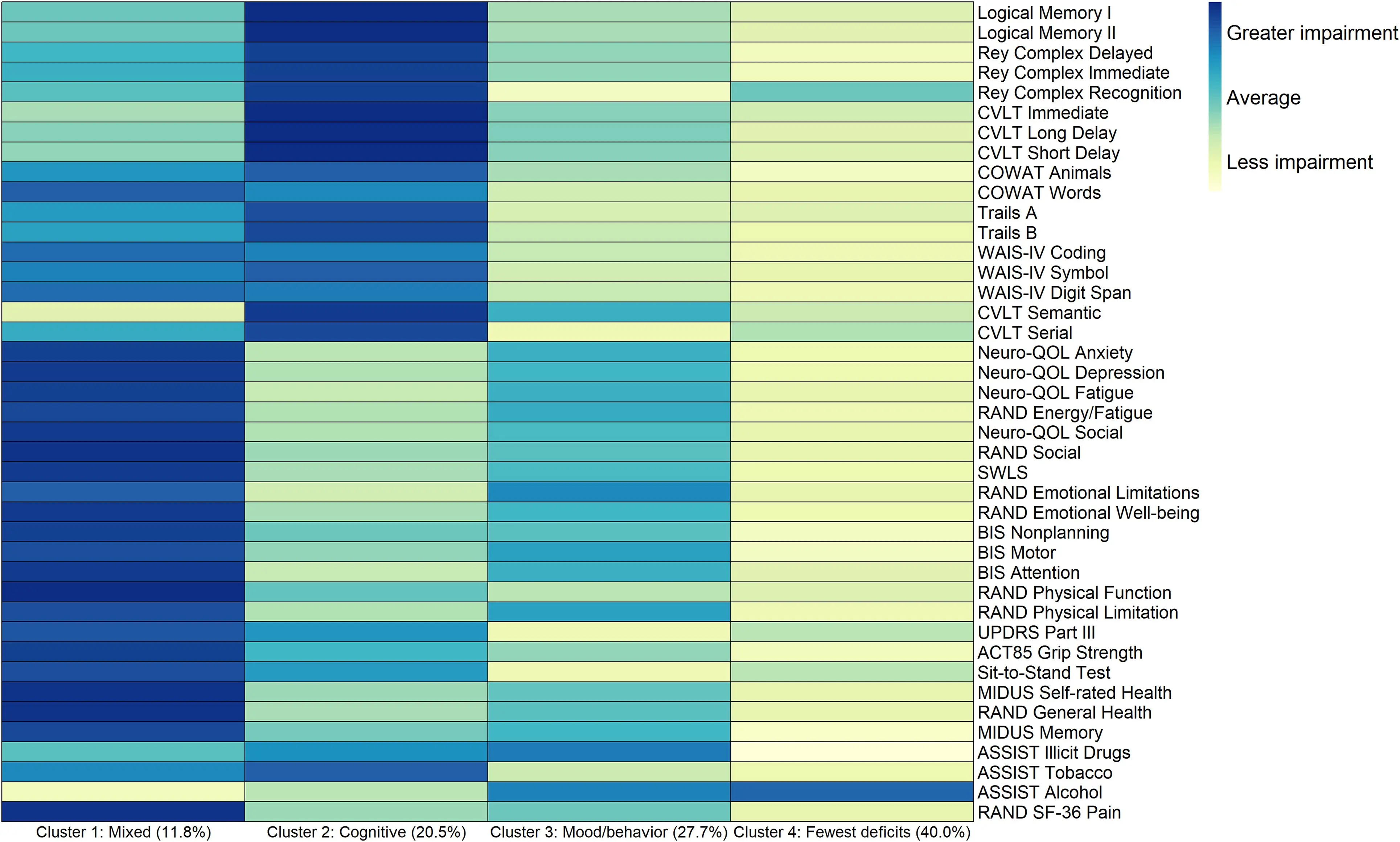

The team used hierarchical clustering on principal components with k-means consolidation to identify clusters, or phenotypes, with shared clinical features, and conducted a secondary objective of investigating differences in brain volume in seven cortical networks across clinical phenotypes in the participants with brain MRI data. The team observed four phenotypes: mixed cognitive and mood/behavioral deficits, predominant cognitive deficits, predominant mood/behavioral deficits, and few deficits across domains—a subgroup of individuals whose cognitive and mood/behavioral symptoms were much lower on average.

The research team identified four clusters or phenotypes: mixed cognitive and mood/behavioral deficits; predominant cognitive deficits; predominant mood/behavioral deficits; and few deficits across domains—a subgroup of individuals whose cognitive and mood/behavioral symptoms were much lower on average.

“Although there have been other phenotype studies, they have not looked this comprehensively across the 40+ symptoms that could be associated with TBI,” Dr. Kumar says. “Clustering provides a novel approach to classification that helps legitimize the uniqueness of recovery among individuals while creating a starting point to consider targeted interventions.”

Correlation With Biomarkers

Dr. Kumar and his colleagues subsequently evaluated objective neuroanatomical correlates of their clusters using magnetic resonance imaging data from a subset of 168 patients, analyzing brain volumes in seven brain-mapped cortical networks across the four phenotypes.

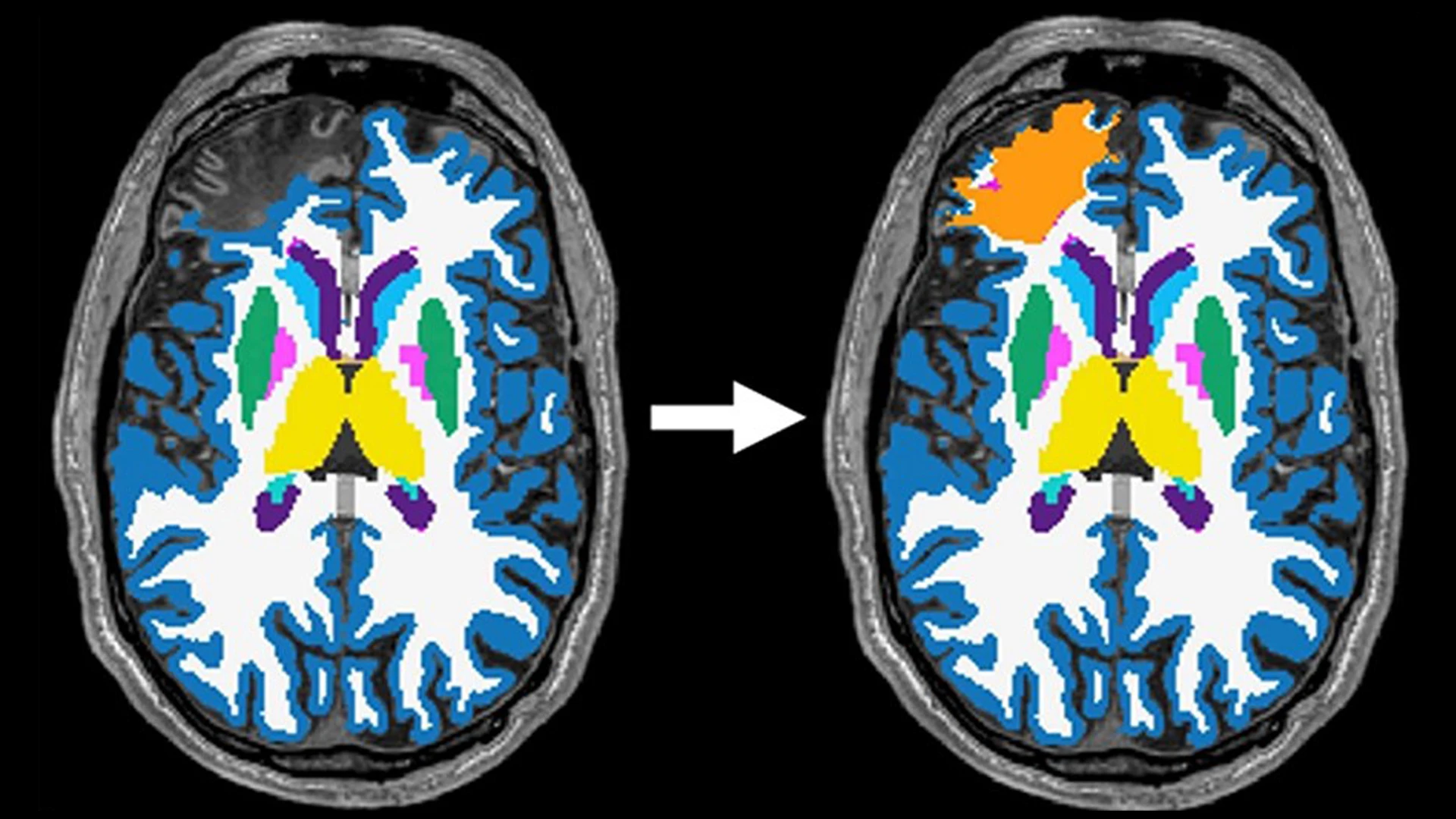

This necessitated developing an innovative lesion correction methodology to enable brain volume estimations among patients with large cortical lesions who would otherwise be excluded—a huge innovation in the field of TBI research, according to Dr. Kumar.

“Large brain lesions are quite common after significant TBI, and most off-the-shelf imaging software cannot handle these lesions to accurately calculate brain volumes from MRIs,” says Dr. Kumar. “Our LETBI investigator team, led by our collaborator Dr. Brian Edlow and his lab at Harvard, developed a way to accurately calculate volumes for these participants with lesions so we could include them in this analysis, which lessens the likelihood of a biased sample.”

Cortical lesions can be a common feature of traumatic brain injury. However, as cortical lesions can lead to inaccurate surface renderings in automated segmentation pipelines, patients with large lesions could be excluded from studies, which can contribute to non-random missingness bias and limits the generalizability of findings. In this phenotype study, the team applied a lesion-correction methodology, which screened all T1-weighted images for the presence of cortical lesions. Lesions that disrupted the cerebral cortex were traced by a study investigator, and multiple investigators confirmed that cortical lesion tracings covered the entire lesioned area and that the lesion boundary did not extend into ventricles. Investigators then merged cortical lesions with the initial white matter segmentation, generating a "lesion-corrected" white matter mask.

The team found the predominant and severe cognitive deficit phenotype was associated with lower cortical volumes in executive control, dorsal attention, limbic, default mode, and visual networks, compared to the phenotype of few deficits across domains. They also observed lower volumes in dorsal attention, limbic, and visual networks in the predominant mood/behavioral deficit phenotype than in the phenotype with few deficits.

“When you have volumes that are statistically significantly lower, it pushes the evidence in favor that what you are seeing in the clinical phenotype is not just noise; it is pathological,” says Dr. Kumar.

Unanswered Questions Fuel Further Study

Contrary to expectations, Dr. Kumar says the team did not observe major differences in brain volumes between the mixed global deficits phenotype and the phenotype with few deficits. This, he suggests, could be the result of the relatively small mixed global deficits sample size or it could mean individuals in this phenotype are more resilient. Furthermore, the apparent overlap in cortical network volumes that are depressed in the predominant cognitive and predominant mood phenotypes is of interest, suggesting there is no clear highly specific pathology linking networks to deficits.

A heat map characterizing average values of neurobehavioral measures by cluster assignment, where darker colors represent greater impairment and lighter colors represent less impairment. Individuals in cluster 1 had mixed trait deficits spanning across most multidimensional clinical measures. Persons in cluster 2 had predominant cognitive deficits, while those in cluster 3 predominantly had mood and behavioral deficits. Individuals in cluster 4 had the fewest cognitive, mood, neurobehavioral, and physical deficits in the sample.

Supported by another grant from the Department of Defense, researchers at the Brain Injury Research Center of Mount Sinai and national collaborators are conducting a similar study among veterans with TBI to see whether the same phenotypes are observed. They plan to complement this undertaking with further studies among other civilian cohorts.

“It could be that we find something different, which would not necessarily invalidate the findings of our study,” he says. “It could just be a different sample that differs from our LETBI cohort in meaningful ways.”

Regardless, Dr. Kumar believes having validated phenotypes will provide clinicians with invaluable insights on long-term heterogeneity in outcomes among people with TBI that complement global function metrics classifications.

“Normalizing phenotypes of brain injury can help influence the care these individuals seek, such as psychological therapies to supplement medical treatment,” Dr. Kumar says. Having more personalized interventions will ultimately facilitate improved outcomes among patients, he adds.

“My hope is not just that my research incrementally advances brain injury science but also makes a meaningful difference in the lives of people living with brain injury.”

Featured

Raj Kumar, PhD, MPH

Assistant Professor of Rehabilitation and Human Performance