For more than 50 years, traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been classified according to three broad descriptors: mild, moderate, and severe. Those categories are derived from the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), which fails to capture the severity or nuance of the injury, or the probable outcomes of treatment.

“We’ve been using a rather simplistic system to place humans into those three categories and believe we can now do better for our patients, provide more personalized care, and conduct more rigorous research,” says Kristen Dams-O’Connor, PhD, Jack Nash Professor in the Department of Rehabilitation and Human Performance at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

Kristen Dams-O’Connor, PhD, Director of the Brain Injury Research Center at Mount Sinai, is co-leading an international initiative to develop a more holistic and comprehensive way of conceptualizing traumatic brain injury (TBI) severity based on deeper clinical and biological phenotyping.

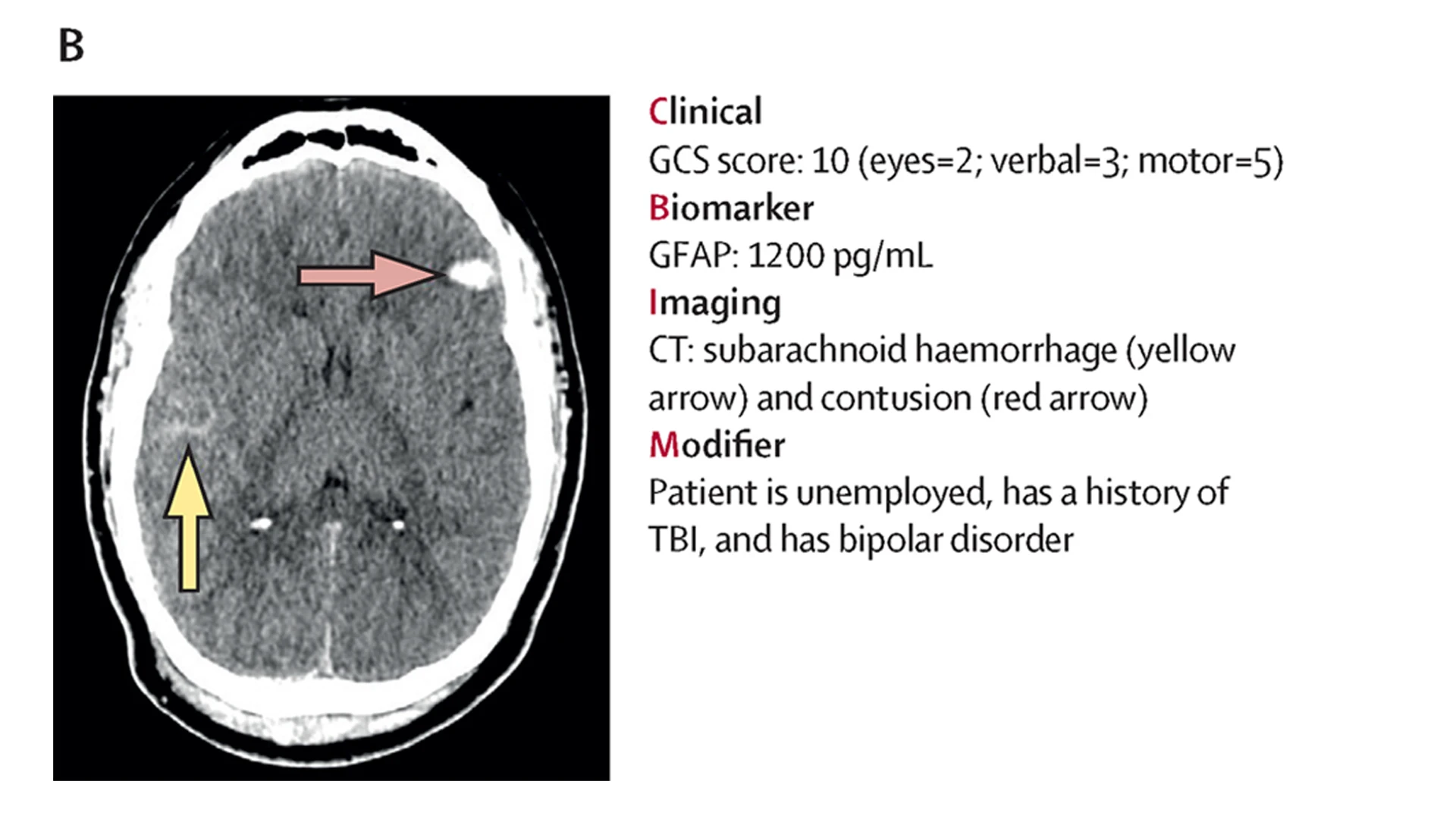

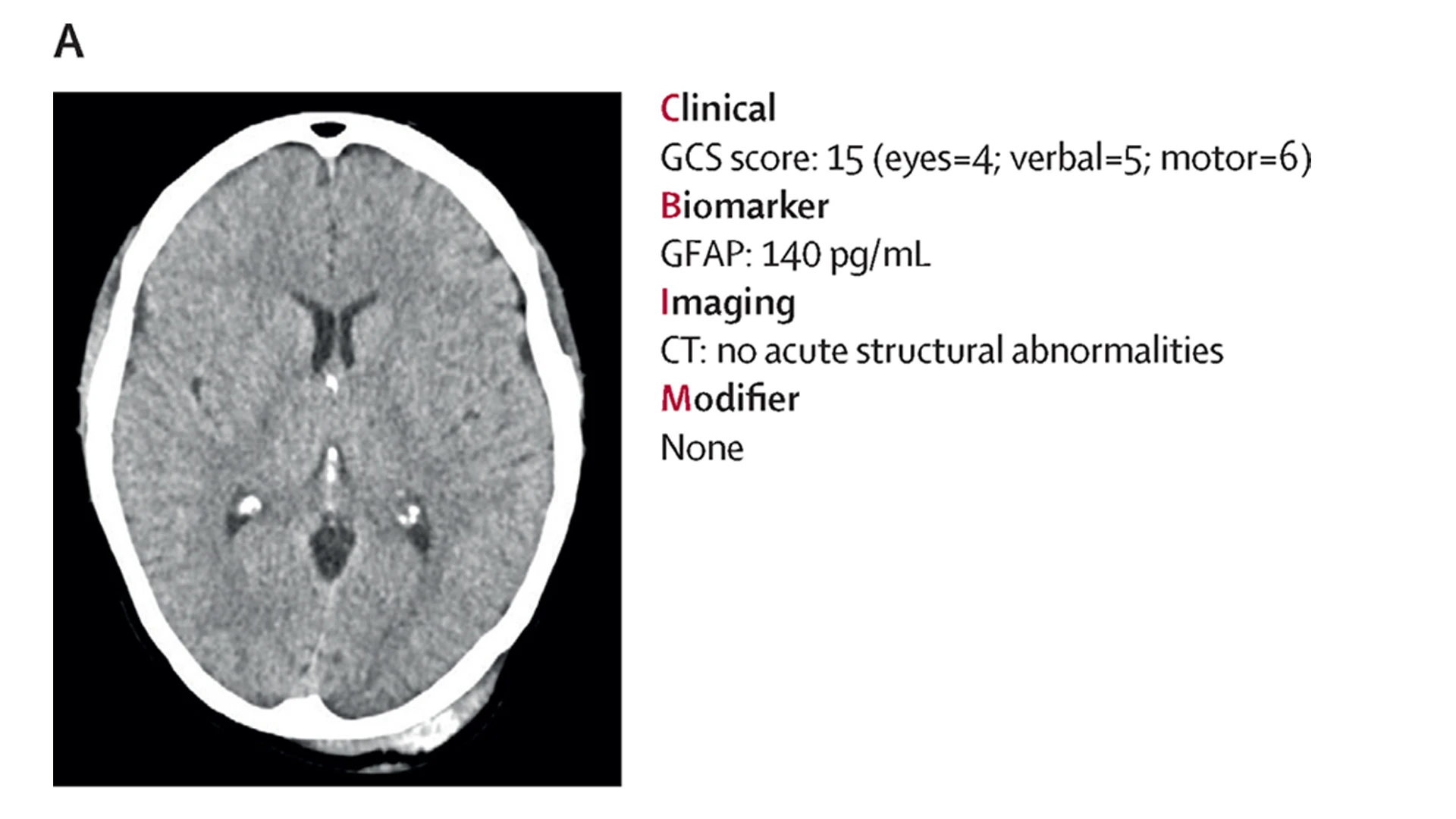

Dr. Dams-O’Connor, Director of the internationally recognized Brain Injury Research Center of Mount Sinai, is working with colleagues across the globe to take concrete action. She is co-leading an initiative, along with other experts in the field, to develop a clinical, biomarker, imaging, and modifier (CBI-M) framework for characterizing traumatic brain injury—a more holistic and comprehensive way of conceptualizing brain injury severity based on deeper clinical and biological phenotyping.

Primary manuscripts by the project’s six working groups were published in recent months, though actual implementation of the new TBI protocol will require a series of validation studies, a determination of its applicability beyond the acute phase of TBI, and strategies for integrating it into clinical practice.

A Revamp Long Overdue

An estimated 50 million people worldwide sustain a traumatic brain injury annually, with a cost to the global economy of around $400 billion. TBI has gotten increased attention in the United States, especially from the media, on head trauma sustained from high-impact sports such as football, although more common causes of isolated TBI include falls among older adults, motor vehicle accidents, and domestic violence.

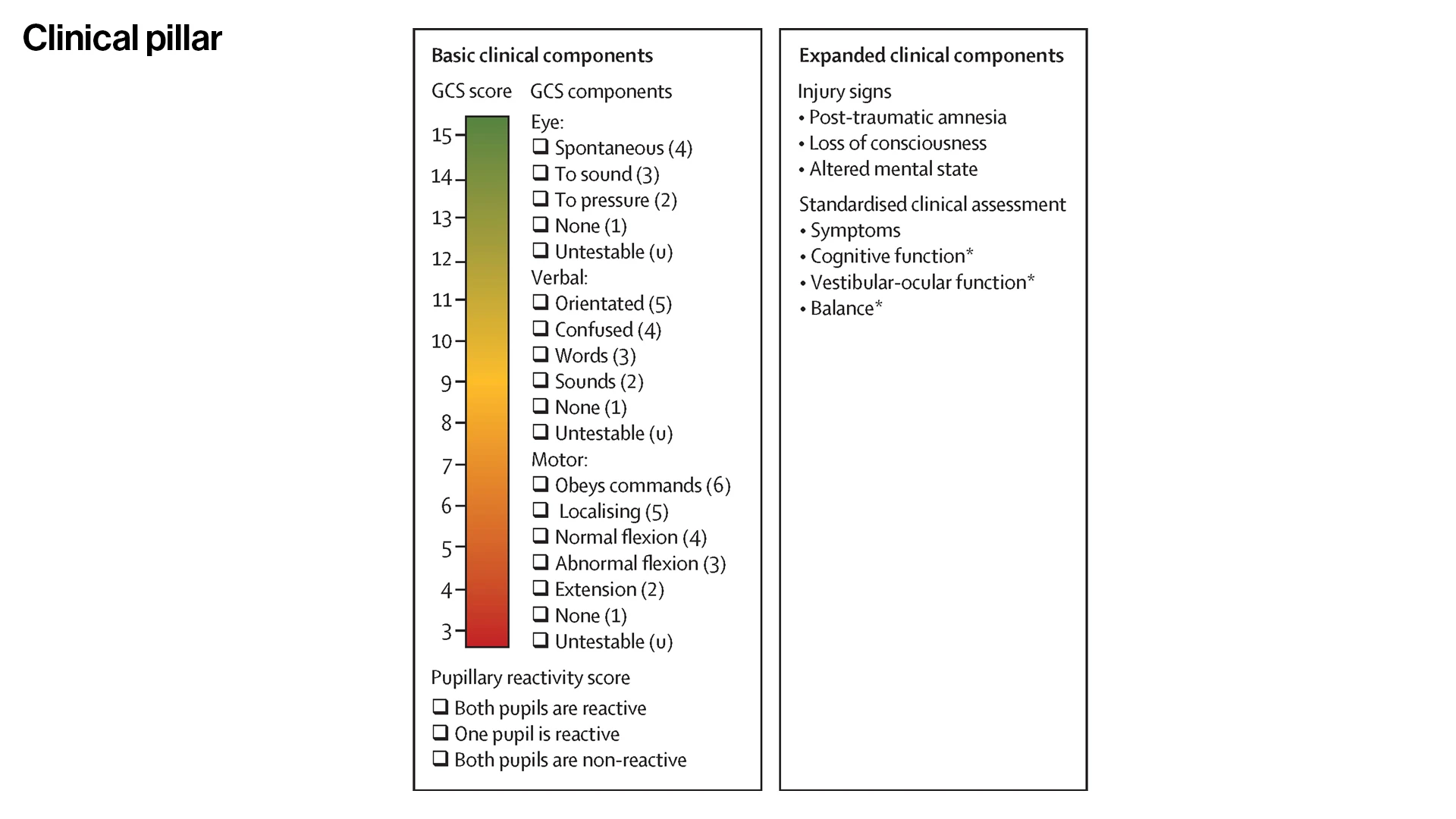

For such head injuries, the GCS has been used since 1974 to measure a person’s level of consciousness by evaluating three key factors: eye opening (scored 1-4), verbal response (scored 1-5), and motor response (scored 1-6). “Mild” is defined as a total score of 13-15; “moderate” as a total score of 9-12; and “severe” as a total score of 3-8.

However, the limitations of this system, as outlined by members of the global team in The Lancet in June 2025, can impact the care a person receives immediately following and years after a TBI.

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) has been used since the 1970s to assess the severity of brain injury.

The diagnostic tool classifies severity into three broad categories on a 15-point scale:

Mild (13-15), Moderate (9-12), and Severe (3-8).

The categorical system lacks nuance, is based on a single clinical parameter, and lacks biomarkers.

“Within the mild category, you could have someone who sustained a blow to the head with no loss of consciousness and a brief transient gap in memory,” says Dr. Dams-O’Connor, who leads multiple large-scale studies investigating the chronic health sequelae of TBI and leads the steering committee for the National Institutes of Health TBI Severity and Nomenclature Initiative. “And in the same category, you could have someone whose brain injury resulted in 20 minutes of unconsciousness and a small brain bleed. These are very different injuries. The range of treatment and recovery after a TBI is huge, and three broad categories don’t tell us enough about what an individual patient needs.”

The development of a more precise and widely applicable system was one of the main recommendations of the U.S. National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine 2022 Roadmap for Accelerating Progress in TBI. The National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke supported the TBI Severity Classification and Nomenclature Initiative to address this high-priority need in the field.

Dr. Dams-O’Connor worked with the Steering Committee to create six working groups of TBI experts and scientists, federal partners, and people living with a traumatic injury and their care partners. In all, 94 participants from 14 countries contributed to developing the newly proposed framework.

While GSC remains a foundational block of the proposed new classification system, developers worked diligently on a new multidimensional framework for improved characterization of TBI built on four “pillars,” each rooted in the latest science, technology, and clinical practice.

Clinical Pillar

Involves a clinical assessment of pupillary reactivity response based on one or both pupils. It also includes assessment of post-traumatic amnesia as an expanded clinical component, as well as evaluation of signs and symptoms such as duration of unconsciousness and/or altered mental state, cognitive function, vestibular-ocular function, and balance, as measured by validated clinical assessment tools, to refine prognosis and recommendations for follow-up care.

Biomarker Pillar

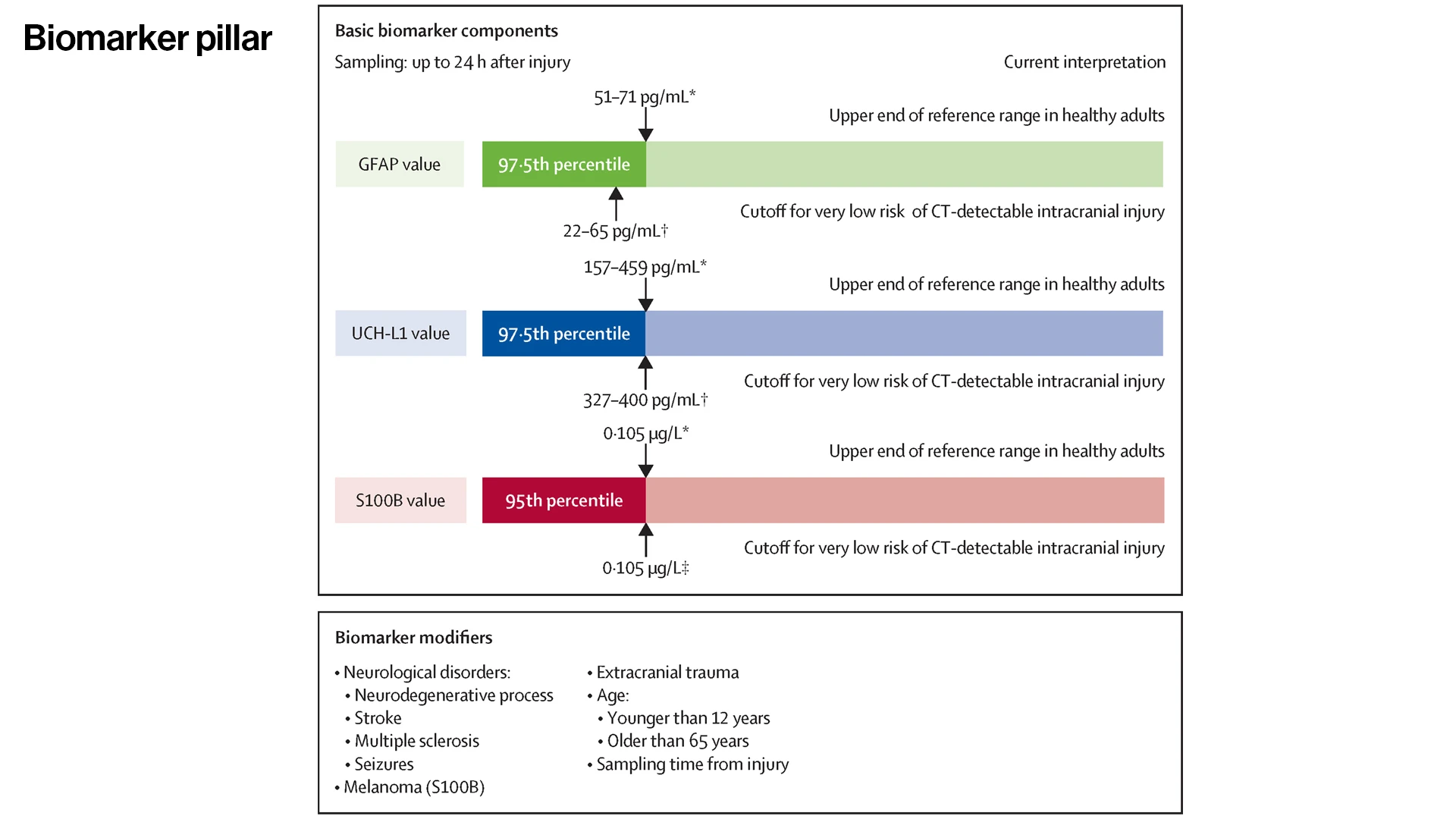

Blood biomarkers are an exciting new tool for informing triage, diagnosis, and treatment of TBI, providing a clinically accessible window into pathophysiology. Although biomarker assays for TBI are not yet in widespread use, developers of the new framework recommended acute post-TBI measurement of one or more of the following biomarkers: glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), and S100 calcium-binding protein B (S100-B). Both GFAP and UCH-L1 have been cleared by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) based on scientific evidence supporting their utility in TBI diagnosis and care management.

Imaging Pillar

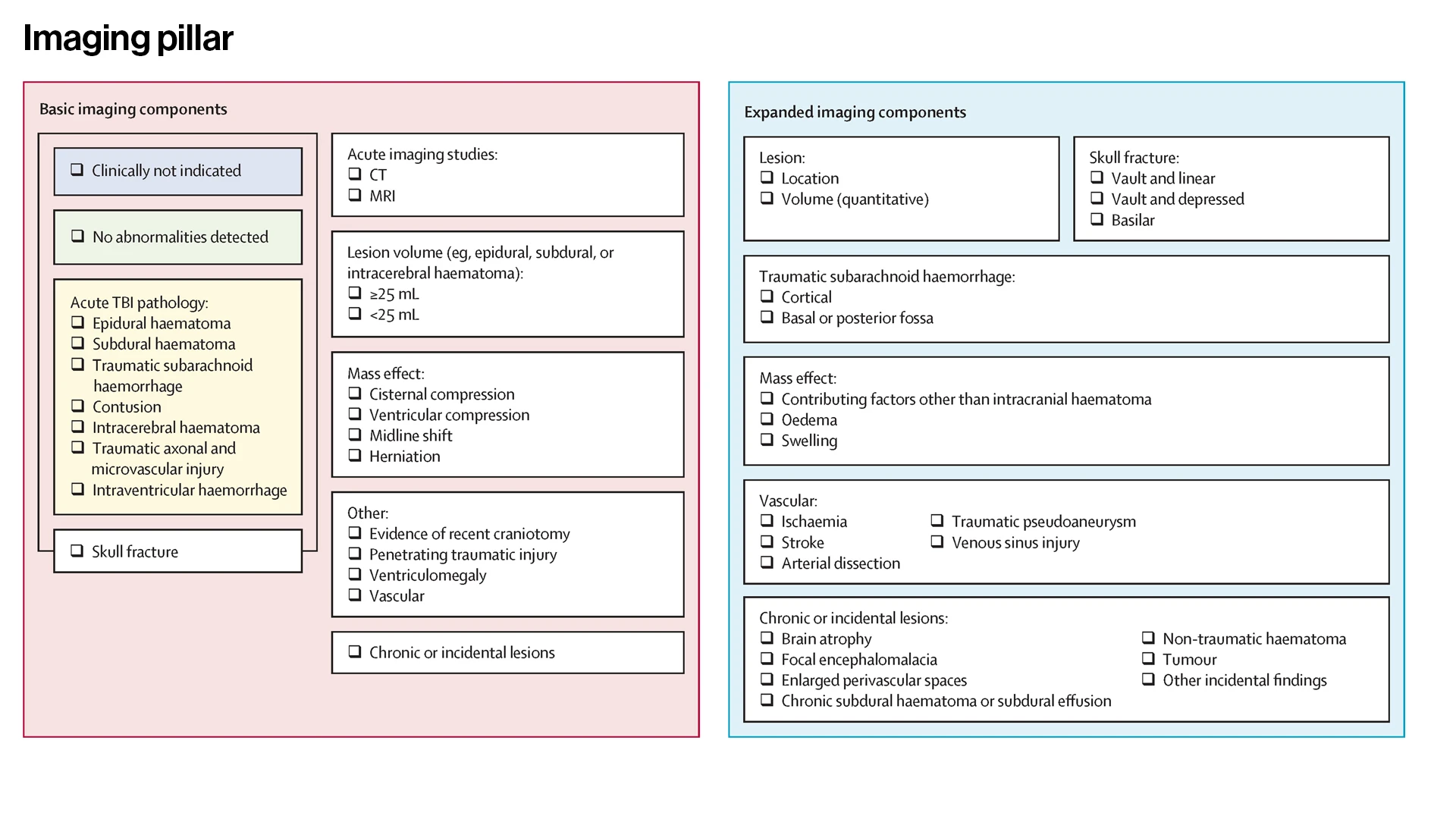

Because neuroimaging is an important source of information about degree and neuroanatomical location of brain injury, this working group focused on use of a computed tomography (CT) scan within the first 24 hours of injury. While its experts recognized that MRI is more sensitive than CT and can provide additional information such as diffusion metrics, they also knew that CT is the most commonly used and readily accessible imaging modality in acute care. Recommendations were also made for documentation of lesion volume, presence and sequelae of mass effect, and other common neuroimaging findings that can be informative for providing personalized care.

Modifier Pillar

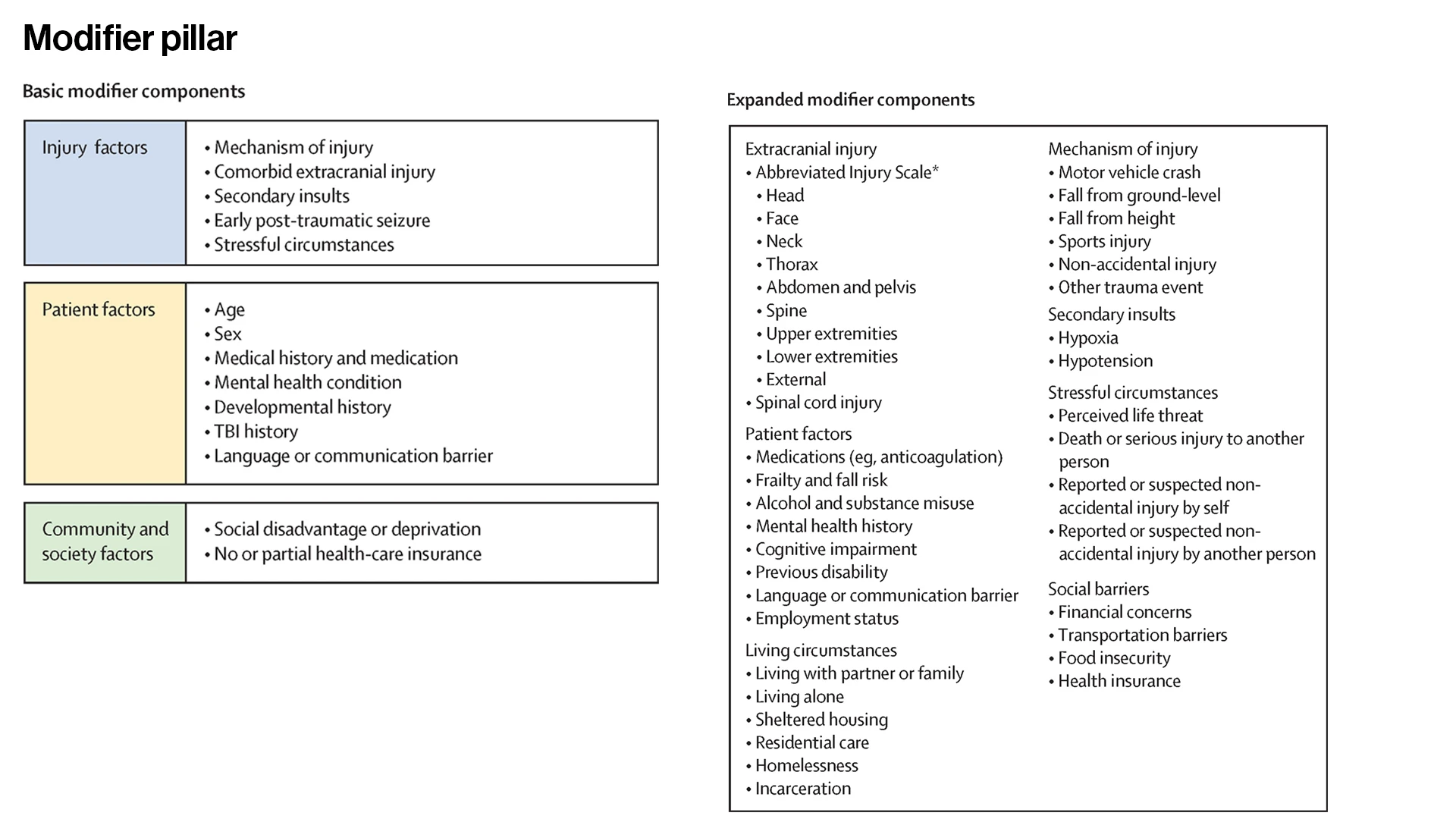

It is well established that the clinical presentation, recovery, and outcome following TBI can be influenced not only by biomechanical and physiological features of the injury, but by psychosocial and environmental factors that can modify the effects of the injury. Thus, this pillar includes injury-related factors, patient-related factors, and community and society-related factors. The latter is particularly novel for the field as it encourages consideration of things such as geographic location, cultural-linguistic background, and pre-injury mental health so the care teams can leverage strengths and identify and overcome potential barriers to optimize care and recovery.

Next Steps

In creating a new platform for classifying TBI, the working teams realized its vast potential to both aid patients and enable scientists to design clinical trials focused on the physiologically relevant features of TBI. According to Dr. Dams-O’Connor, components of the new framework are already being used as enrollment criteria for recently initiated clinical trials at Mount Sinai and other academic centers. Development of a pillar-based severity score and prognostic risk calculator to inform individualized care are further goals of researchers.

“We don’t present our framework as a finished product,” acknowledges Dr. Dams-O’Connor. “It still requires extensive field-testing and validation, but our hope is that the considerable work our teams have done will now pave the way for more breakthrough research that could potentially benefit the millions of people globally who experience a traumatic brain injury.”

Featured

Kristen Dams-O'Connor, PhD

Director of the Brain Injury Research Center