Mount Sinai neuroscientist Andrew Varga, MD, PhD, has long wanted to conduct a randomized controlled trial to explore the links between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). But the available funding options could not accommodate one.

“One of the problems with studying Alzheimer’s is that you generally need to track people for periods of time that are much longer than the five-year funding cycle that agencies will provide,” says Dr. Varga, Associate Professor of Medicine (Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“We came up with a solution. We proposed to do a clinical trial looking at some of the blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer’s as a proxy among cognitively normal people with the assumption that higher biomarker levels suggest greater risk for progression to the disease.”

The resulting study is known as Effects of Successful OSA Treatment on Memory and AD Biomarkers in Older Adults (ESSENTIAL). This multicenter, three-month randomized open-label study with two-year follow-up will assess whether patients who are successfully treated for obstructive sleep apnea demonstrate a slower decline in cognitive function and lower levels of plasma AD biomarkers (neurofilament light, amyloid beta, and phosphorylated tau) compared to those who are untreated.

The ESSENTIAL study builds on previous investigations into the links between OSA and AD involving Dr. Varga. He found that OSA is associated with an increase in amyloid and tau burden, and that self-reported OSA treatment delayed the onset of mild cognitive impairment by 11 years. He also found that even a brief withdrawal of acute positive airway pressure treatment results in significant overnight changes in AD biomarkers and an observed change in neurofilament light, a marker of neural injury, which is associated with increases in intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation.

“These findings suggest that apnea is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, and a clinical trial presents an opportunity to assign causality more specifically,” says Dr. Varga, who is one of three Principal Investigators for ESSENTIAL.

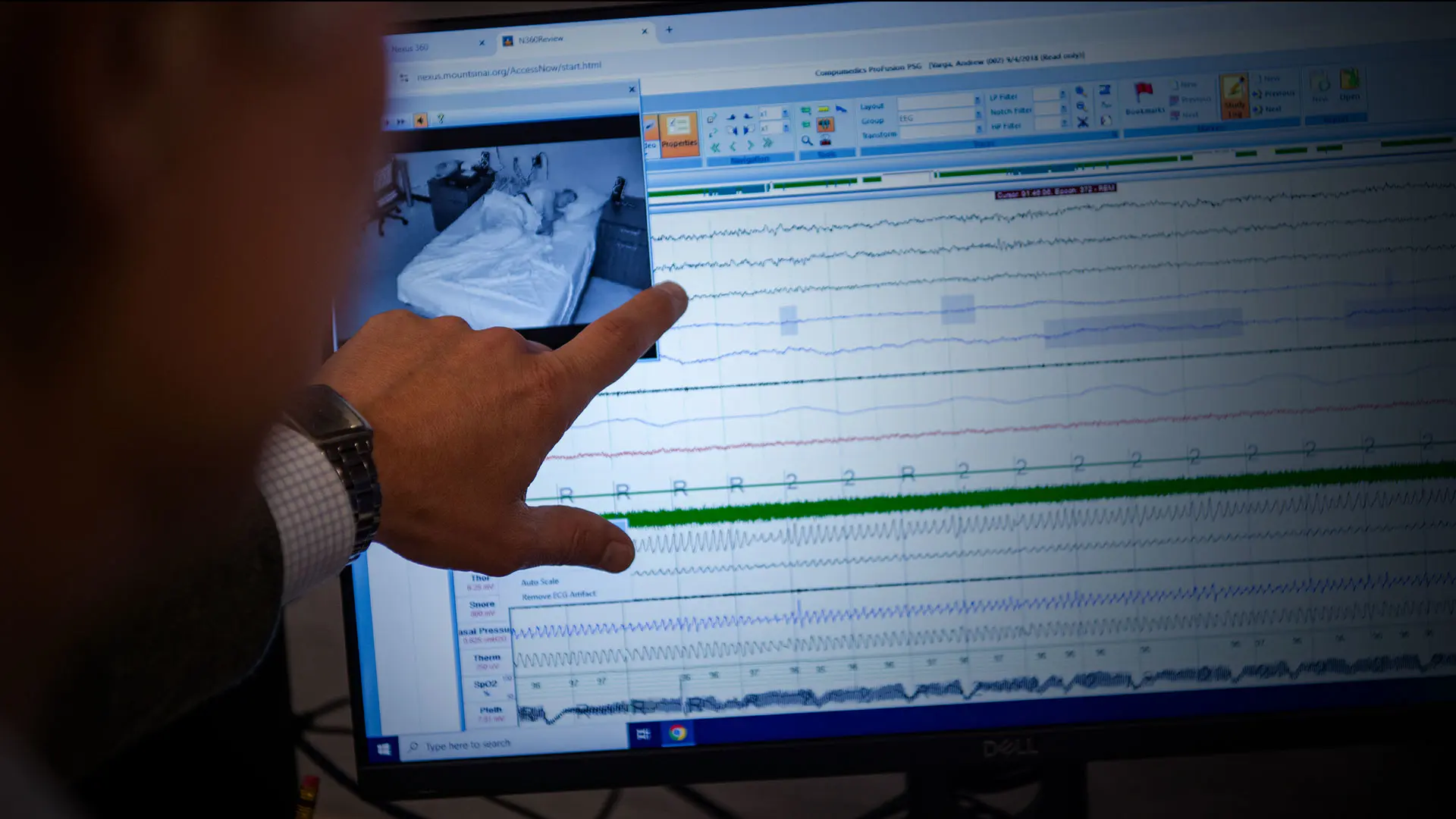

A Mount Sinai-led study will examine possible links between obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and Alzheimer's disease.

Dr. Varga, right, with Research Coordinator Daphne Valencia, hopes to address one of the key challenges of clinical studies involving patients with OSA.

The study will recruit 200 participants from sleep clinics at Mount Sinai, New York University, the University of Pittsburgh, and the University of Arizona. The study is open to cognitively normal older adults (telephone interview for cognitive status>29) between ages 55 and 85 who have been diagnosed with moderate to severe OSA. Participants also must not currently be receiving treatment for OSA, or not received treatment within the last six months, and be willing and able to undergo treatment.

Once recruited, participants will be randomized to a treatment group or a waitlist control group that will be offered treatment at the end of the three-month clinical trial. Dr. Varga says the treatment cohort will be offered a choice of therapeutic interventions—continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), oral appliance therapy, or positional therapy. Through this novel approach, he hopes to address one of the key challenges of conducting clinical studies among patients with OSA.

“Several prior clinical trials for the treatment of sleep apnea focused exclusively on treatment with CPAP and were negative,” Dr. Varga explains. “However, people in the CPAP treatment cohort either did not use their CPAP or used it for three to four hours despite sleeping seven to eight hours. By offering a choice of treatments, we can measure how well they use it and whether it is effective in lowering their sleep apnea hypopnea index in a meaningful way, such as improved memory and reduction of AD biomarkers.”

Dr. Varga says efficacy of therapy will be assessed based on “effective” apnea hypopnea index, which combines the reduction in OSA intensity with the average nightly duration on- and off-therapy. Assessments will include polysomnography, actigraphy (an assessment of patient movements done using wearable monitoring devices, such as an Apple Watch), cognitive evaluations, and blood draws at baseline and three months. All participants who were treated during, or began treatment at the conclusion of, the three-month trial will then be followed for up to 24 months. Changes observed in their AD biomarkers and cognition during that follow-up will be compared against those from a cohort of untreated controls consisting of study participants who declined treatment and non-randomized patients subsequently recruited from participating clinics.

“That follow-up is a sufficient duration for us to evaluate treatment-associated cognitive decline and changes in AD risk reflected in clinical biomarkers, even in preclinical AD,” Dr. Varga says. “The data will help inform a future, longer-lasting trial using decline to mild cognitive impairment and AD as outcomes.”

Recruitment for the ESSENTIAL study is underway at Mount Sinai, and Dr. Varga believes the outcomes could be beneficial for thousands of people with OSA. “For example, it could change the way these therapies are covered by insurers,” he says. “But I would love to see the medical community think differently about AD risk so there is more screening and more urgency to treat OSA beyond symptoms.”

From left: Sarah Chu, Research Coordinator; Sara Hishinuma, Research Coordinator; Saranya Ravi, Research Manager; Ms. Valencia; David Rapoport, MD, Professor of Medicine; Dr. Varga; Indu Ayapp, PhD, Professor of Medicine; Katarina Martillo, Research Coordinator; Lily Zhou, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow; Pasha Boulgakov, Data Scientist; Tom Tolbert, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine; Ankita Kumar, Research Coordinator; and Sajila Wickramaratne, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow