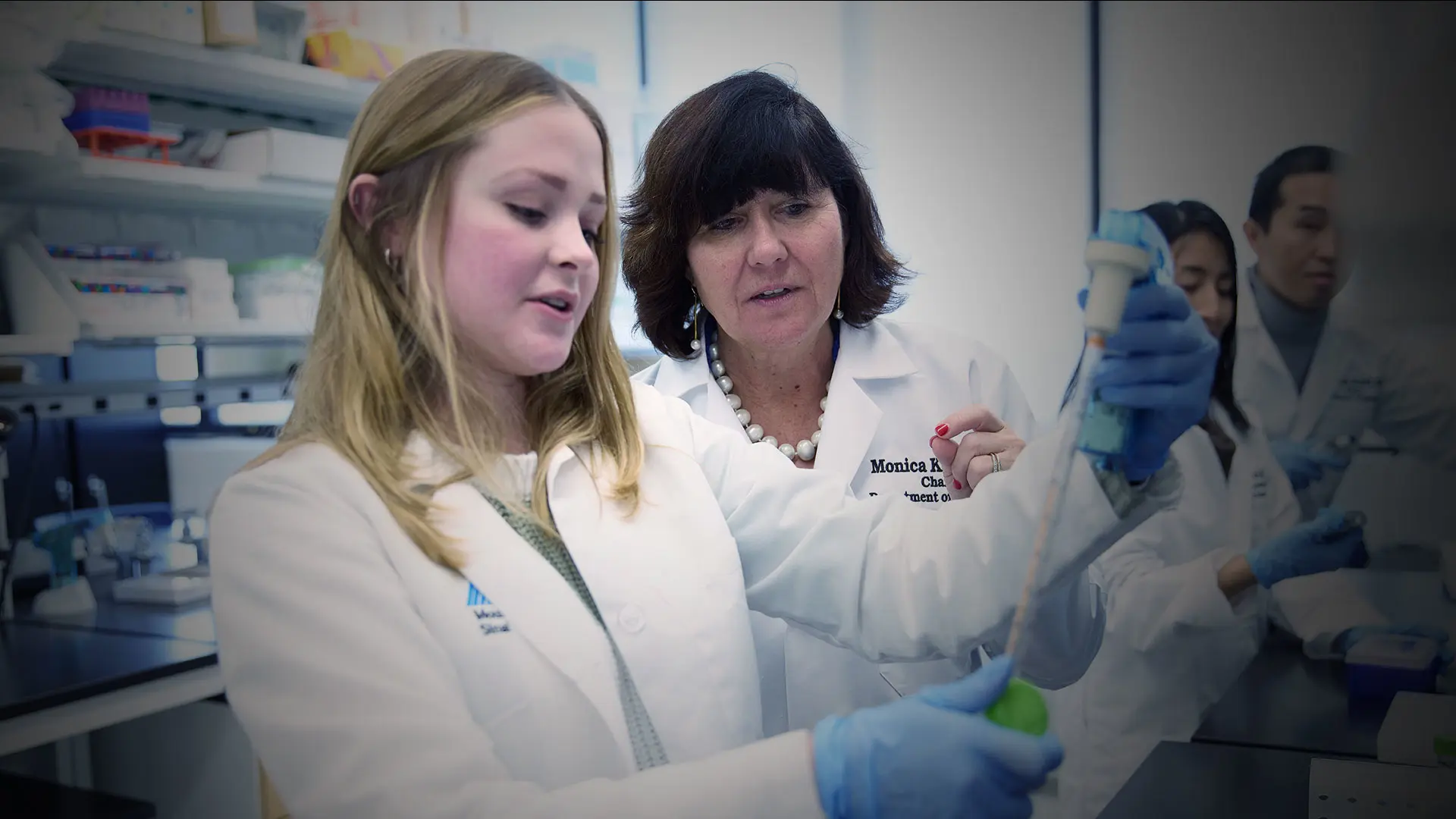

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, scientists observed a curious phenomenon in some patients with asthma: they seemed less susceptible to the rapidly spreading virus than those without the chronic respiratory condition. Among those investigators was Monica Kraft, MD, internationally known for her asthma research and, as of July 2022, the Murray M. Rosenberg Professor of Medicine and Chair of the Department of Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“When we looked at cases coming from Wuhan, China, and from Europe, we noticed comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which significantly enhanced the severity of the SARS-CoV-2 infection,” she recalls. “But there was no asthma among them, which we found very interesting. So we went to public databases where we could look at gene expression in asthma, then returned to our lab to culture airway epithelial cells from participants with allergic asthma and expose them to the kind of type 2 inflammation an asthmatic lung would experience.”

What Dr. Kraft and her team at the University of Arizona Health Services, where she was Deputy Director of the Asthma and Airways Disease Research Center at the time, discovered was quite revealing. They learned that certain proteins produced by patients with mild to moderate eosinophilic asthma downregulate the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor that allows SARS-CoV-2 entry to airway cells, resulting in a less severe course of the disease. In a review published in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the researchers reported that SARS-CoV-2 invades host cells using the ACE2 receptor with the assistance of transmembrane protease serine 2, which cleaves the SARS-CoV-2 protein, and that the co-expression is found in both the upper and lower airways.

“When we looked at cases coming from Wuhan, China, and from Europe we noticed comorbidities such as obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. ... But there was no asthma among them, which we found very interesting.”

- Monica Kraft, MD

The ACE2-inhibiting protein is interleukin-13 (IL-13), which is associated with robust eosinophilic type 2 inflammation that affects 50 to 60 percent of individuals with asthma. While much work remains to determine the exact mechanism, IL-13 is believed to have an underlying protective effect against infection by stimulating production of sticky mucus that effectively ensnares viruses before they can infect airway cells.

“Not only do cytokines such as IL-13 suppress viral entry by reducing expression and production of the ACE2 receptor, but we believe they actually cause a decrease in the number of ciliated airway epithelial cells, thus changing the phenotype of those cells away from being infectable,” explains Dr. Kraft. “We think this happens over time, but need to study this systematically to prove the hypothesis. This is not to say, however, that we should negate the importance of treating type 2 inflammation to improve asthma symptoms and reduce asthma attacks. Controlling type 2 airway inflammation with inhaled corticosteroids, systemic steroids, and biologics when they’re needed is critical to managing patients with eosinophilic asthma.”

Based on her rigorous studies to date, Dr. Kraft is now exploring whether the mechanisms of asthma-related inflammation confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Anecdotal evidence has shown that patients with more advanced type 2 inflammation seem to follow a less severe course, but little is known about where that threshold of severity lies. Past research by Dr. Kraft has reported that patients with more serious asthma (described as more frequent exacerbations with the need for more medications) were more likely to experience ICU admission or death as a result of COVID-19. These findings suggested to scientists there might be a threshold of asthma severity, or a phenotype indicated by the use of add-on therapy, for which the risk is most substantial.

As for therapeutic strategies, Dr. Kraft has made considerable progress with surfactant protein-A (SP-A), an important mediator of pulmonary immunity. In the case of asthma, SP-A assists in the resolution of allergic airway inflammation by promoting eosinophil clearance from lung tissue through apoptosis, or programmed cell death. “We’ve known for years that SP-A has antibacterial and antiviral properties,” she explains, “but now we know it has anti-inflammatory properties relevant to asthma.”

Building on that research, Dr. Kraft has designed a small peptide of SP-A for intended use as an inhaled therapeutic in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. That promising treatment, which recently received a $3.4 million small business grant from the National Institutes of Health for further development, is now scaling up through aerosol toxicology testing with the goal of bringing the project to the new drug application stage.

While her work with asthma and SARS-CoV-2 continues, Dr. Kraft has signaled a desire to significantly widen the investigative lens to encompass other globally active viruses such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus that can exacerbate asthma—though science has little knowledge of why.

“We need to create an even bigger picture of how the asthmatic lung handles viruses,” Dr. Kraft emphasizes, “and the research I’ve been doing for years in this field, complemented now by an amazingly gifted research team at Mount Sinai, will lead us, I’m sure, to new scientific and medical solutions for people with asthma.”

Featured

Monica Kraft, MD

Murray M. Rosenberg Professor of Medicine