Groundbreaking work by Mount Sinai researchers have previously identified voltage-gated potassium channels (KCNQ) as novel targets for treating major depression disorder (MDD), as well as explored the use of ezogabine—a potassium channel opener—as a potential therapeutic in that class. Two new studies build on that work, identifying mechanisms that open the door for phenotyping patients.

Led by James Murrough, MD, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry, and Neuroscience, and Director of the Depression and Anxiety Center for Discovery and Treatment at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, the studies looked at the impact of KCNQ channel modulation on brain activity and connectivity among individuals with MDD and anhedonia, which has an estimated prevalence of 70 percent among people diagnosed with depression. These channels were first elucidated as a potential therapeutic target through mouse model neuroscience research conducted by the Friedman Brain Institute at Mount Sinai.

James Murrough, MD, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, was among the first researchers to explore the potential of the KCNQ channel as a novel target for treating major depression disorder. He recently published two papers elucidating the mechanistic foundations of the channel, as well as findings validating the pathway for eventual pharmaceutical development.

Dr. Murrough was the first researcher to investigate that potential through a double-blind randomized study published in the American Journal of Psychiatry in 2021. Although that study did not reach its primary neuroimaging endpoint, it did find that participants administered ezogabine, an anticonvulsant medicine for partial onset seizures, reported greater improvement in their symptoms and ability to experience pleasure than those administered a placebo.

“We are in an interesting space where clinical outcomes are still our gold standard,” says Dr. Murrough. “We are trying to move beyond that to a pathophysiology through neuroimaging and other biological measures, which was the aim of the complementary studies.”

Treatment Normalizes Brain Region Communication

The complementary studies involved secondary analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) from the treatment and control cohorts from Dr. Murrough’s 2021 study. One study, published in Biological Psychiatry in October 2025, investigated the potential of ezogabine to modulate the resting-state functional connectivity among the brain’s main reward regions and larger-scale brain networks such as the posterior cingulate cortex. This cortex is part of the default mode in the brain, which is thought to play a key role in internally directed thought and negative emotions.

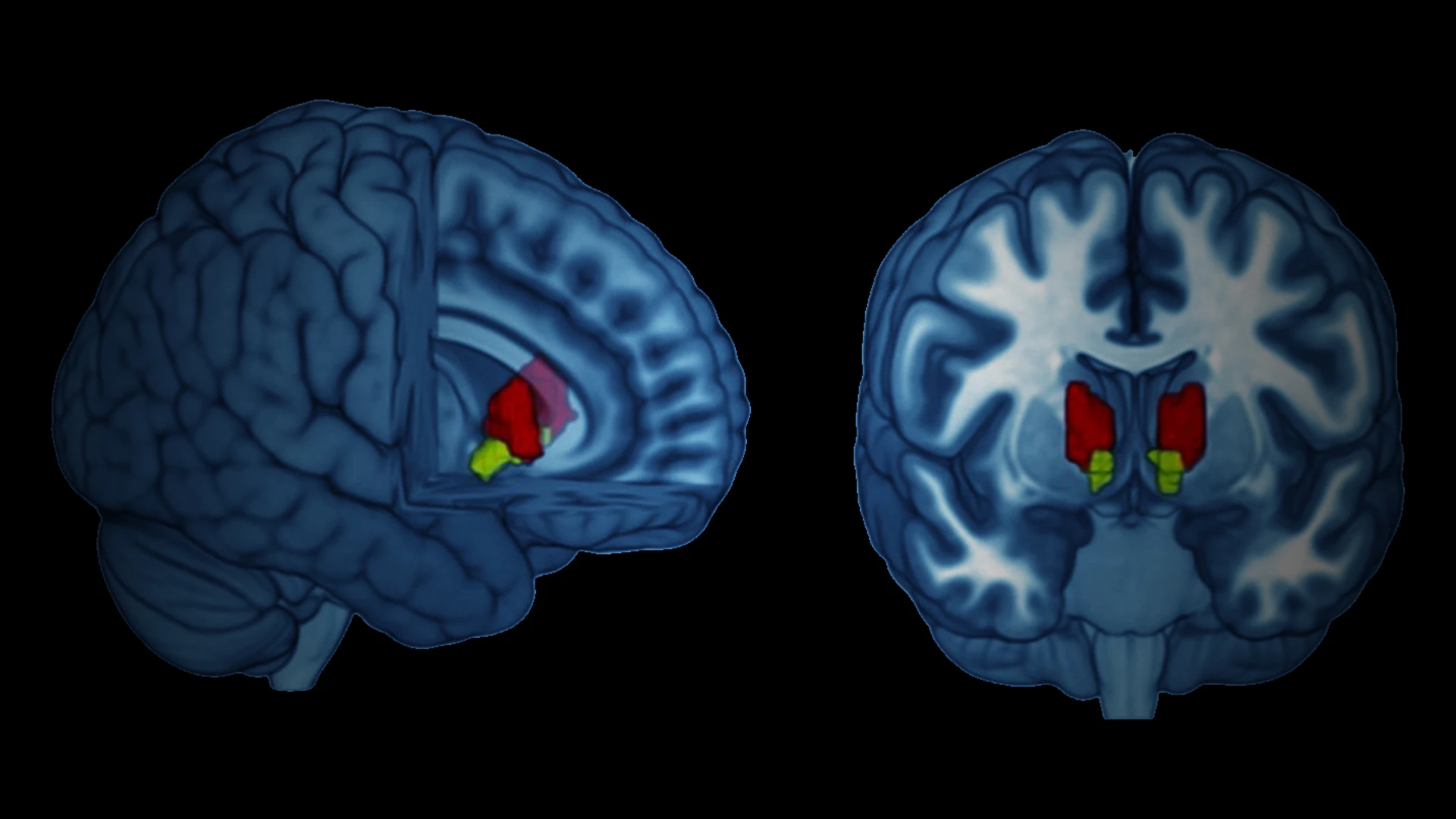

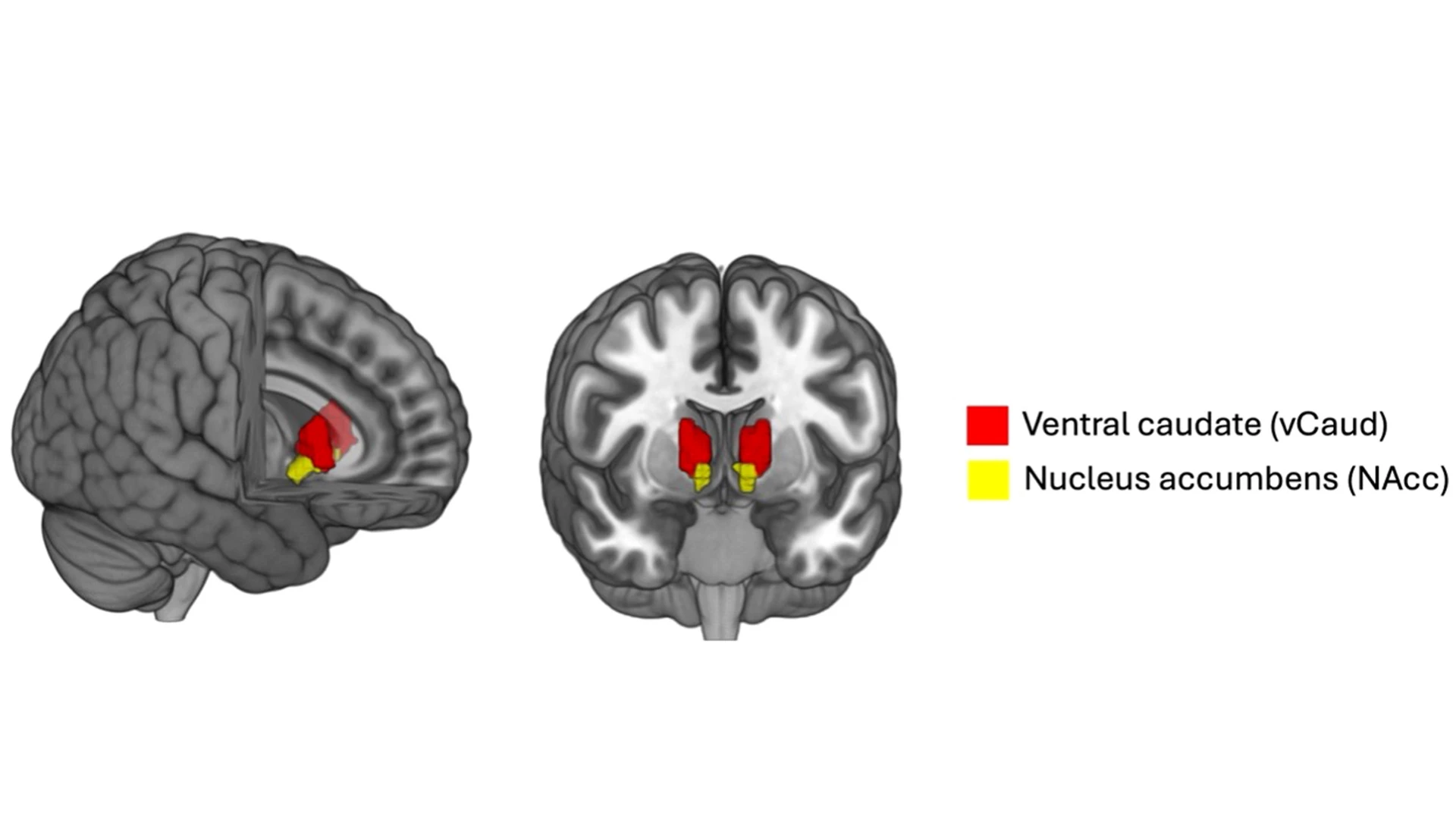

As part of the study, published in Biological Psychiatry, Dr. Murrough conducted MRI scans to assess ezogabine's ability to modulate the resting-state functional connectivity of the brain's reward regions, including the ventral caudate and nucleus accumbens. His team observed significantly reduced connectivity between the reward regions and the posterior cingulate cortex among individuals administered ezogabine compared with placebo.

Dr. Murrough and his colleagues observed significantly reduced connectivity between the reward regions and the posterior cingulate cortex among individuals administered ezogabine compared with placebo. Furthermore, improvements in both anhedonia and depressive syndromes among the treatment cohort compared with placebo were associated with decreased connectivity among the reward regions and the mid/posterior cingulate regions.

“That finding is significant because it suggests a mechanism by which the drugs that target the KCNQ channels may be therapeutic among individuals with depression,” Dr. Murrough says.

A Possible Mechanism Driving MDD Emerges

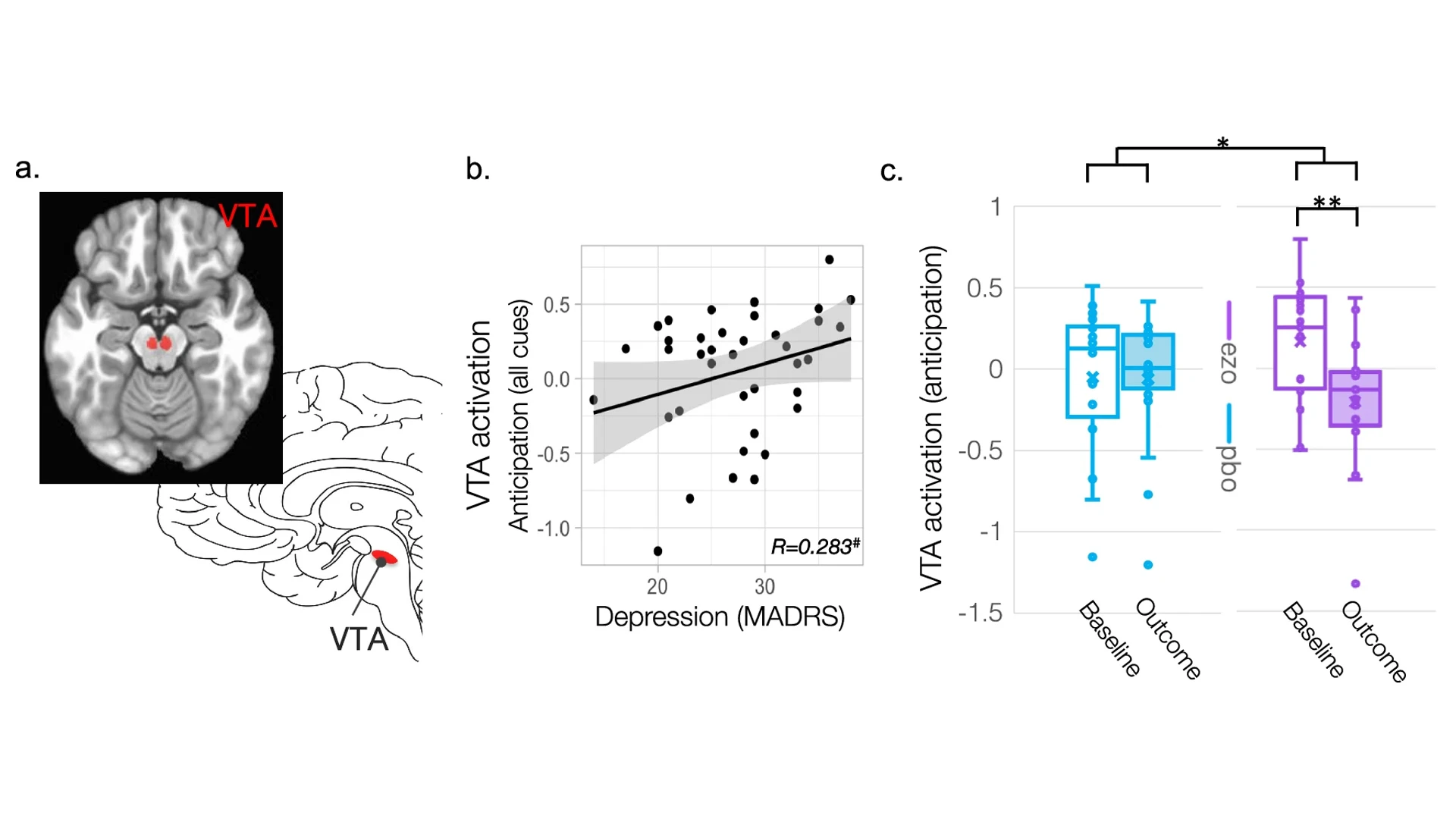

In a concurrent study published in Molecular Psychiatry in March 2025, Dr. Murrough and Laurel Morris, PhD, Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Mount Sinai and Associate Professor of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Oxford, UK, looked at functional MRIs completed during the resting states and during a rewards-based task. They were interested in the impact of ezogabine on the ventral tegmental area, which modulates the ventral striatum and is involved in the production of dopamine.

This area is abnormally overactive among mice models under stress, which is thought to disrupt their ability to detect reward in their environment. The team found that ezogabine normalized hyperactivity of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) among people with depression and anhedonia.

“What this suggests is that this very ancient part of the brain is overactive in depression and may have a role in the communication observed in the other study,” Dr. Murrough says.

A concurrent imaging study, published in Molecular Psychiatry, explored ezogabine's ability to affect the ventral tegmental area (VTA), shown in figure A. Among individuals with depression, higher VTA activation during anticipation was associated with more severe depressive symptoms, seen in figure B. The team also found that ezogabine normalized hyperactivity of the VTA among people with depression and anhedonia symptoms, compared to those administered placebo, seen in figure C.

Although these studies indicate that ezogabine may be an effective treatment for major depressive disorder, Dr. Murrough indicates it is unlikely to be approved for treating MDD by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This is because ezogabine has been gradually superseded by other therapeutic agents for treatment of partial onset seizures.

That unlikeliness to pass FDA muster, however, does not mean the end of the therapeutic target; several pharmaceutical companies are developing, or have indicated an interest in developing, next-generation KCNQ openers that could prove more effective in providing relief from symptoms. Dr. Murrough has completed a second clinical trial of one such candidate.

The validation that KCNQ is effective as a novel target for MDD is exciting for Dr. Murrough, but he has his sights set on the next stage of the research: opportunities for phenotyping patients through identification of the mechanisms involved in the brain region communication that contributes to MDD.

Having the ability to phenotype will facilitate better understanding of the efficacy of the next generation of therapeutic agents, and Dr. Murrough is contributing to that effort through studies that match treatments to subtypes, such as individuals with anhedonia.

“We envision a future where tools such as blood tests and brain scans will help determine the type of depression that patients have, and therefore how best to treat them,” he says. “I think that is going to be an integral part of the practice of psychiatry in the next 5 to 10 years.”

Featured

James Murrough, MD, PhD,

Director of the Depression and Anxiety Center