The failure of the existing system for detecting risk in people on the edge of suicide—relying on suicidal intent—is both stark and well-documented. Around 75 percent of those who took their lives explicitly denied suicidal intent at their last meeting with a health care professional, according to previous studies. Moreover, nearly 20 percent of people who died by suicide didn’t have a diagnosable mental disorder, which is another metric for detecting suicide risk.

Those points were driven powerfully home at the 2025 American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting in Los Angeles, where a panel of four men shared with the audience the tragic loss of their children from suicide. None of them had suicide risk detected in the aftermath of visits to psychiatrists.

Sitting by their side on stage was Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Galynker had assembled the panel as the centerpiece of his presentation on the Narrative Crisis Model (NCM) of Suicide, a dynamic new approach he and his team developed to better understand, assess, and treat the intricate, and often elusive, mental processes that result in suicide.

Igor Galynker, MD, PhD, Professor of Psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, presented the Narrative Crisis Model for detecting and preventing suicidality at the 2025 American Psychiatric Association Annual Meeting in Los Angeles. At the panel, Dr. Galynker invited four fathers who had lost children to suicide, each talking about how their children did not have suicide risk detected via the traditional methods used by psychiatrists. From left to right: Oliver Lignell; Lorence Miller, PhD; Frederick Miller, MD; Dr. Galynker; and Rob Masinter.

“The concept of suicide prevention based on self-reported suicide ideation is misleading and flawed,” says Dr. Galynker. “What’s urgently needed today are alternative suicide risk models that incorporate evidence-based, long- and short-term risk factors to conceptualize an individual’s progression to suicidal behavior. We believe the Narrative Crisis Model is that type of game-changer.”

A New Model With Therapeutic Steps

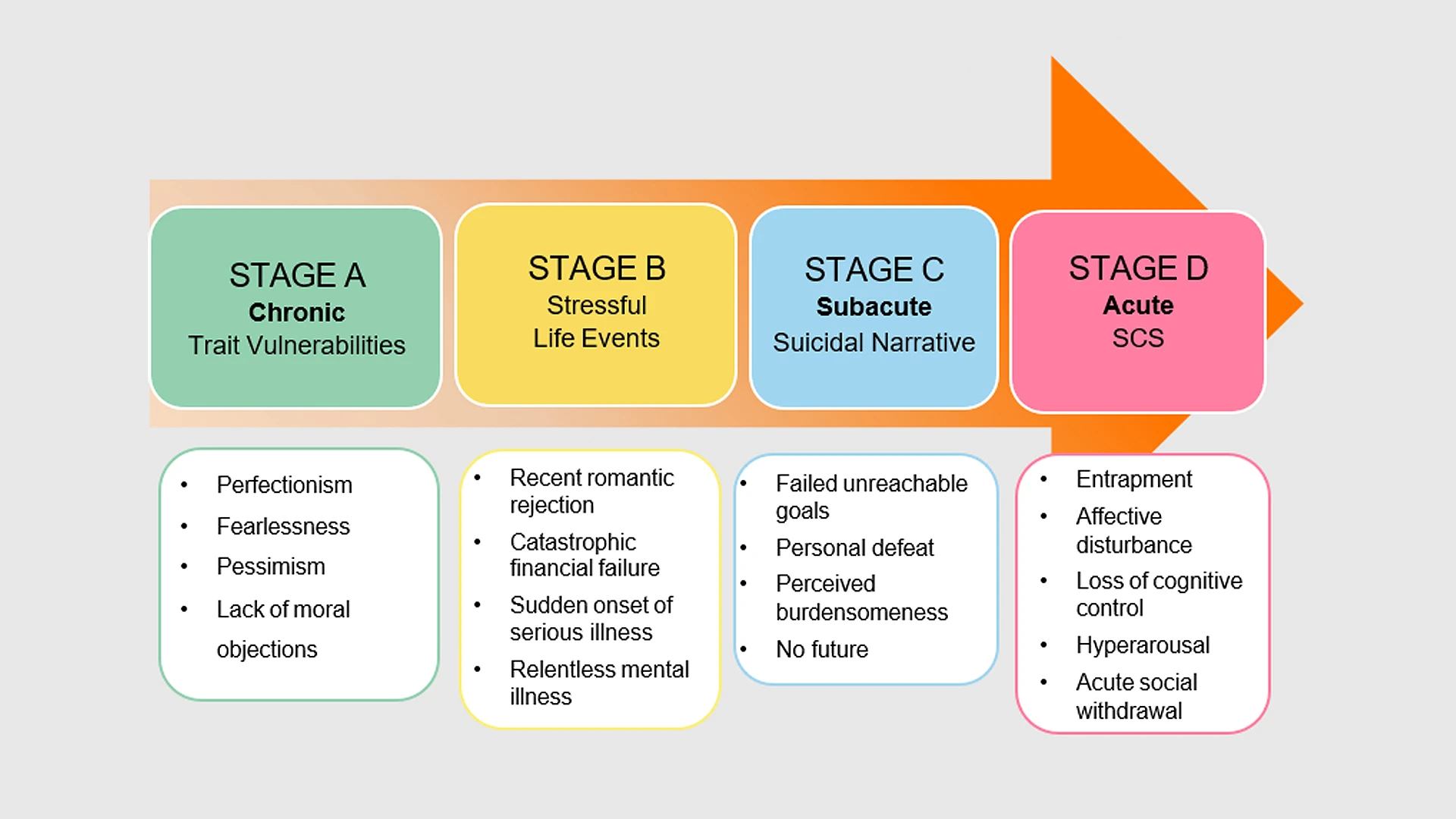

The Narrative Crisis Model is a four-stage template that incorporates chronic, stress-related, subacute, and acute factors associated with suicidal behaviors in an effort to chart an individual’s progression from underlying and chronic vulnerabilities to acute suicidal crisis states. The stages begin with chronic, progressing to stress-related, then to subacute, and ending with suicide crisis syndrome (SCS), the last and most acute stage.

“The NCM holds that when someone with chronic or long-term vulnerabilities—such as childhood trauma, perfectionism, substance abuse, and impulsivity—experiences stressful events, they may develop negative views of themselves and society that we refer to as the ‘suicidal narrative,’” explains Dr. Galynker, who is the founder and director of the Mount Sinai Suicide Prevention Research Laboratory. “The suicidal narrative is characterized by a distorted self-image driven by feelings of loneliness, social disconnection, burdensomeness, and a painful and desperate perception of having no future. When it’s sufficiently intense, the suicidal narrative can trigger the next stage, eventually leading to suicide crisis syndrome, where recurrent feelings of entrapment or frantic hopelessness prevail.”

800,000

people around the world die by suicide each year

50-70%

of suicide decedents had seen a health care provider within one month of their deaths

~75%

of suicide decedents have denied suicide intent at their last meeting with a health provider

Thus, self-reported suicidal ideation is a poor and inefficient indicator of suicidal crises

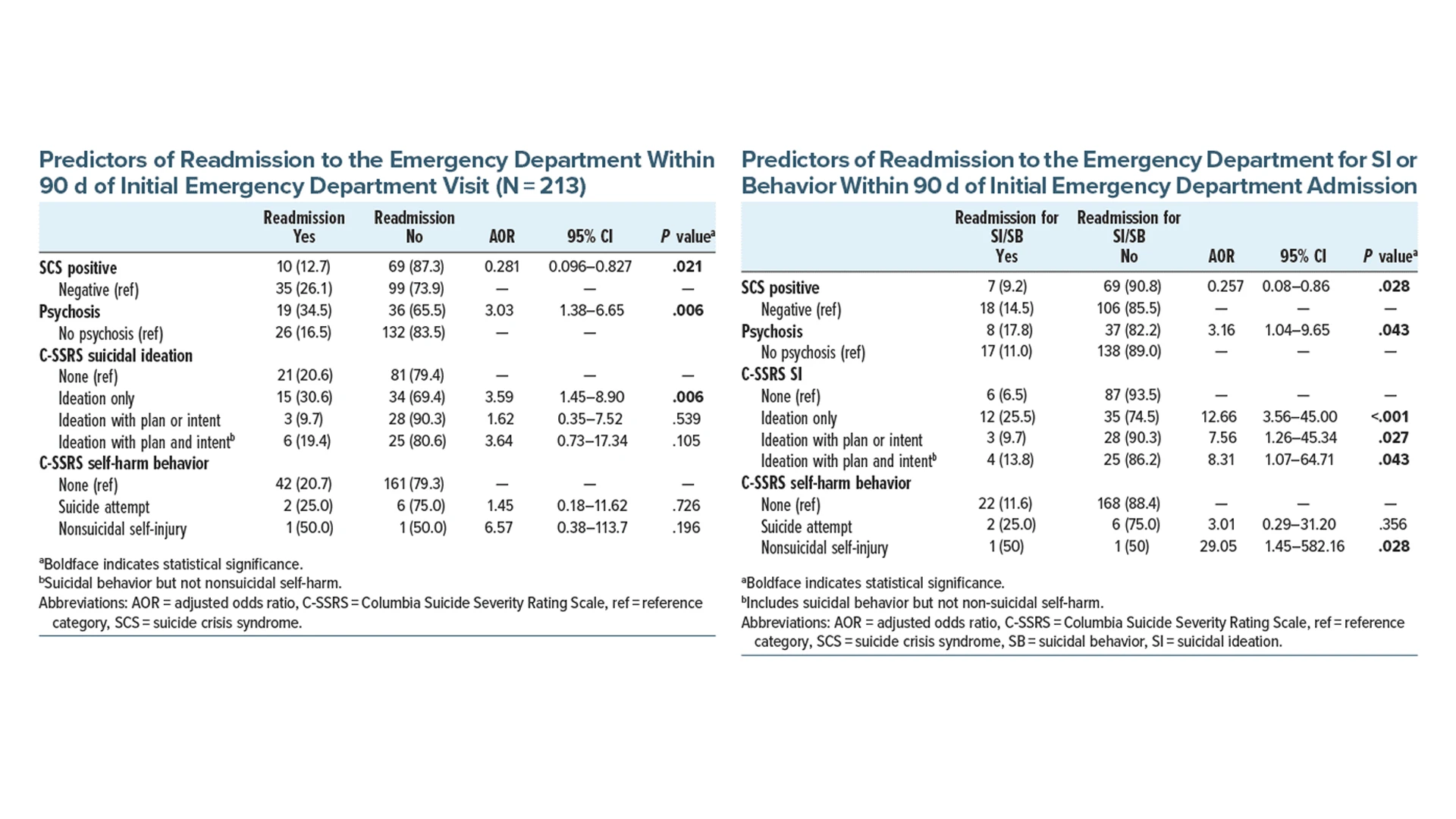

Dr. Galynker’s research team has been validating the NCM and tracking its impacts. In a 2024 study in the Journal of Clinical Psychology, his team found that a diagnosis of SCS among patients admitted to an urban emergency department was associated with a 75 percent reduction in three-month readmission rates compared to individuals without the diagnosis. And a paper in Personalized Medicine in Psychiatry, published in June 2024, underscored the NCM’s ability to provide an innovative framework in which each stage can be addressed with empirically supported interventions, including pharmacological treatment, dialectical behavior therapy, and mindfulness-based stress regulation, depending on the severity of the condition.

Over the past 18 years at Mount Sinai, Dr. Galynker has closely followed emotionally vulnerable patients to better understand their symptoms and struggles, and why a risk model informed by evidence-based psychological milestones along a progression from chronic factors to acute suicidal crisis is urgently needed to replace the current standard of self-reported suicidal ideation at a given time.

The Narrative Crisis Model posits that when individuals with heightened baseline vulnerability to suicide experience negative stressful life events, they may develop certain views of themselves and society, which are referred to as the “suicide narrative.” The individual transitions through increasingly acute states, which could culminate in suicidal behavior.

Suicide crisis syndrome (SCS) is an acute suicidal state of affective and cognitive dysregulation that makes suicidal behavior possible, was developed in an iterative manner across more than a decade of research. Of note, suicidal ideation is not necessary for the diagnosis of SCS.

As researchers pointed out in the Personalized Medicine in Psychiatry study, which was supported by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, an empirically grounded conceptual framework such as the NCM can greatly enhance the clinician’s ability to understand the patient and assess both imminent and future suicidal risk. Just as importantly, it can help to forge a therapeutic alliance between patient and physician, which not only reduces the well-documented negative emotional responses of doctors to high-risk patients, but also decreases the shame of patients when they experience suicidal thoughts. Consequently, the NCM can increase their readiness to fully disclose those experiences.

Making the NCM Part of Clinical Practice

Having demonstrated that the SCS exists, Dr. Galynker and his team are now determined to integrate the NCM into widespread clinical practice.

The first step down that pathway is for the SCS to be included in the latest edition of APA’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). An application was submitted, and the team is providing more information and supportive data for a resubmission in 2026, as requested by the DSM-5-TR committee. The new package includes a soon-to-be-published Mount Sinai study showing that the reduction in hospital readmission rates for suicide-prone patients is entirely mediated by a reduction in the intensity of the SCS from time of admission to discharge.

“We firmly believe that SCS belongs in the DSM because it addresses a treatable, suicide-specific diagnosis and illness,” Dr. Galynker says. “Once it’s accepted in the DSM, everyone in the field will know about the model, and teaching it will become mandatory.”

Researchers had run a study to assess the suicide crisis syndrome (SCS) diagnosis's utility as a clinical tool within a real-world clinical setting, using readmissions after an initial emergency department (ED) admission as a metric. The findings, published in the Journal of Clinical Psychology, showed that of the 213 patients studied, after controlling for covariates, a SCS diagnosis reduced readmission risk by approximately 72 percent (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.281) for any reason and almost 75 percent (AOR = 0.257) for suicidal presentations, while suicidal ideation and self-harm behavior upon initial ED visit either increased readmission risk or were noncontributory. The protective effect of SCS was consistent across levels of severity of both suicidal ideation and self-harm behavior.

However, the NCM is not intended to replace the current methods of suicide detection, but meant to be implemented alongside them. “Our goal instead is to make our comprehensive and evidence-based model an accepted part of clinical practice across the United States, and worldwide,” he says.

Meanwhile, Mount Sinai is advancing that educational effort by establishing the International Suicide Prevention Center, under the direction of Dr. Galynker, with the NCM serving as its linchpin. Professionals will be able to access instructive information, including descriptions of cases and interviews with experts, from the Center’s website. In addition, Dr. Galynker continues to spread awareness of the new model through his lectures and presentations.

“Suicide doesn’t occur out of the blue,” says Dr. Galynker. “It results from a stageable mental process, and once you understand what to specifically look for, you can take meaningful steps to help prevent it.”

Featured

Igor Galynker, MD, PhD

Director, Mount Sinai Suicide Prevention Research Laboratory; Professor of Psychiatry, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai