Researchers at the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment at the Mount Sinai Health System are testing a groundbreaking gene therapy treatment for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) associated with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. It is the first study of its kind for Phelan-McDermid syndrome, with implications that could reach beyond this rare genetic disorder.

“This research may change the developmental trajectory for children with Phelan-McDermid syndrome and could lead to similar treatments for other genetic forms of autism,” says Alex Kolevzon, MD, Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for the Mount Sinai Health System, Clinical Director of the Seaver Autism Center, and a principal investigator of the multicenter trial.

Alex Kolevzon, MD, Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for the Mount Sinai Health System, and Clinical Director of the Seaver Autism Center, is involved in a first-of-its-kind study for children with Phelan-McDermid syndrome. The trial explores an investigational gene therapy by Jaguar Gene Therapy, which aims to restore function to the faulty SHANK3 gene associated with the disorder.

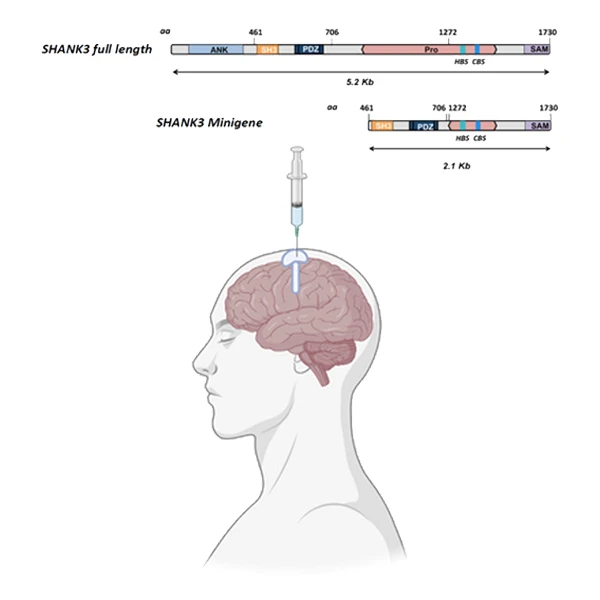

The study investigates the use of JAG201, developed by Jaguar Gene Therapy, which delivers a functional SHANK3 mini-gene via adenovirus vector to target the faulty gene in patients’ neurons. Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and Boston Children’s Hospital are study collaborators.

Therapies for ASD have typically managed symptoms, but this treatment represents a concrete step in tackling the disorder at its genetic core.

“There's an enormous amount of heterogeneity in both the underlying biology and clinical presentation of autism, so it has been challenging to develop treatments that are significantly impactful,” Dr. Kolevzon says. “But with the advent of new genetic technologies and the knowledge that autism is primarily genetic in origin, we are now seeing some major advances.”

Targeting Autism-Related Genes

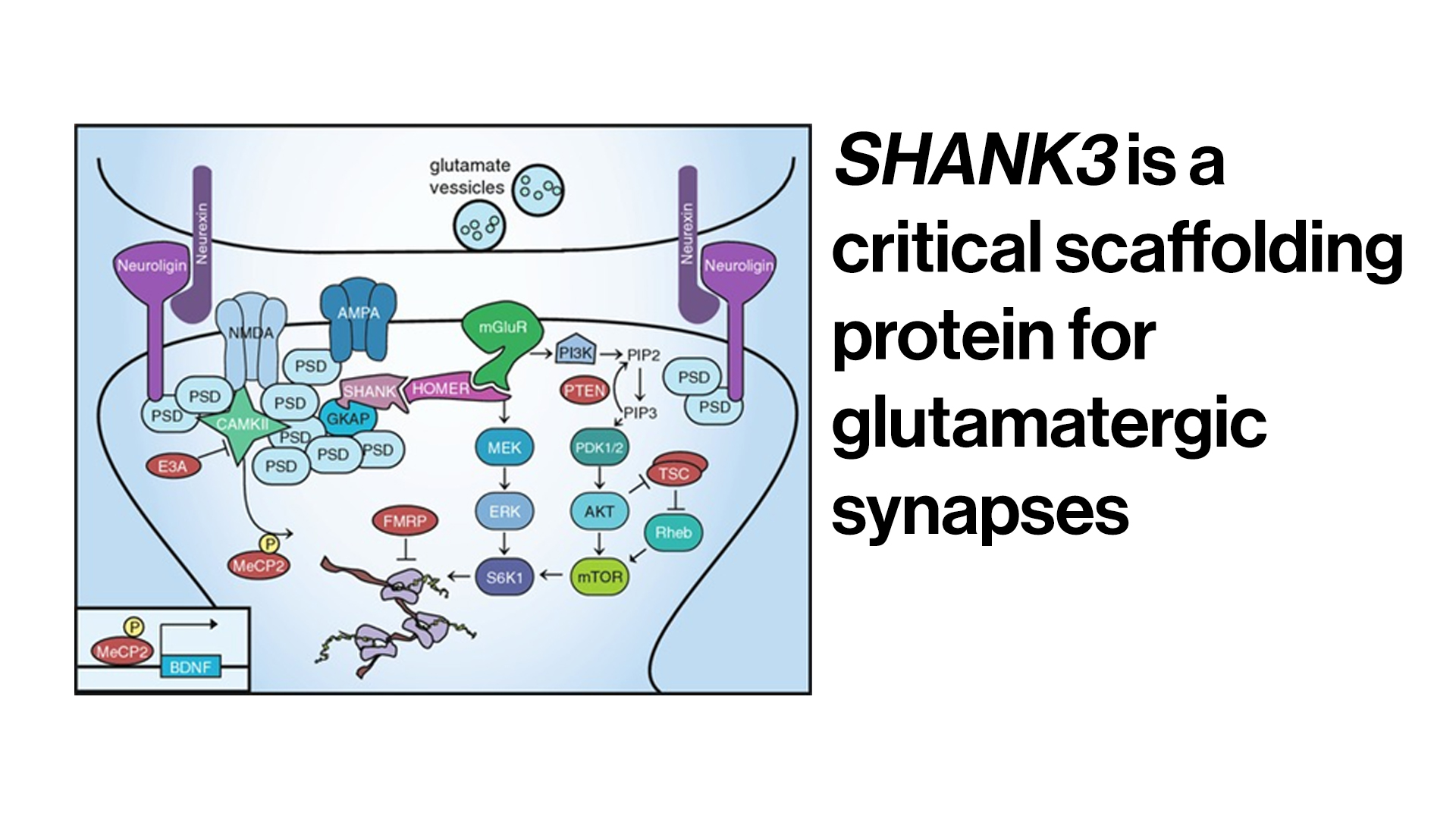

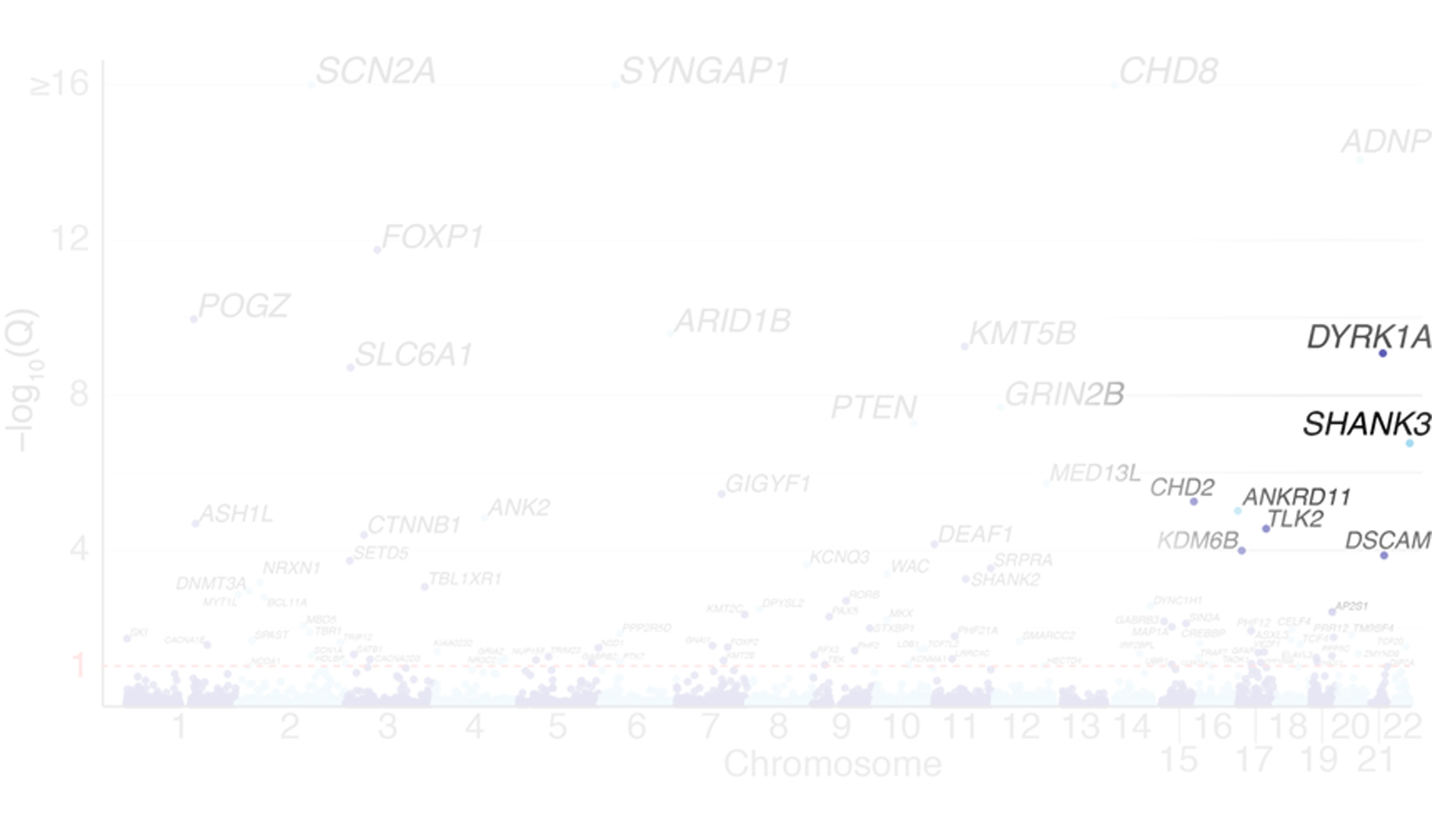

Researchers have identified several hundred genes associated with ASD. Phelan-McDermid syndrome—where approximately 65 percent of patients are also diagnosed with ASD—is caused by a deletion or sequence variant of a single gene, SHANK3. This monogenic cause makes the disorder a promising one to treat using gene therapy.

SHANK3

haploinsufficiency is understood to cause Phelan-McDermid syndrome

The missense gene is known to be among the most common genetic forms of autism

65 percent

of patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome are also diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder

Phelan-McDermid syndrome is rare, occurring in an estimated 1 in 10,000 births, and SHANK3 mutations are found in approximately 1 to 2 percent of people with ASD. Although symptoms can vary in severity, individuals with the syndrome experience substantial developmental delays. “Generally speaking, they tend to be minimally verbal, not toilet trained, and cannot live independently,” Dr. Kolevzon says. “A significant percentage also have regression, losing language and motor skills.”

The JAG201 treatment consists of a one-time infusion into the brain, injected into the lateral ventricle. This first-in-human study will focus on six children between the ages of 2 and 3, since it is likely that young children would see the most gains from the treatment. The researchers plan to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and clinical activity of the treatment, comparing two different doses.

JAG201 is a one-time infusion into the brain, injected into the lateral ventricle. As the full-length SHANK3 gene is too large to be packaged by the adenovirus-associated viral vector, JAG201 contains a miniaturized version of the SHANK3 gene where core functional binding sites are conserved.

The trial launched in February 2025 at the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai, and three children have received the infusion so far. The team will follow the patients for five years and hopes to report preliminary findings in late 2025 or early 2026.

Potential for Functional Improvements

Early safety data have been encouraging, and there is reason to be optimistic that the treatment could result in functional improvements, Dr. Kolevzon says.

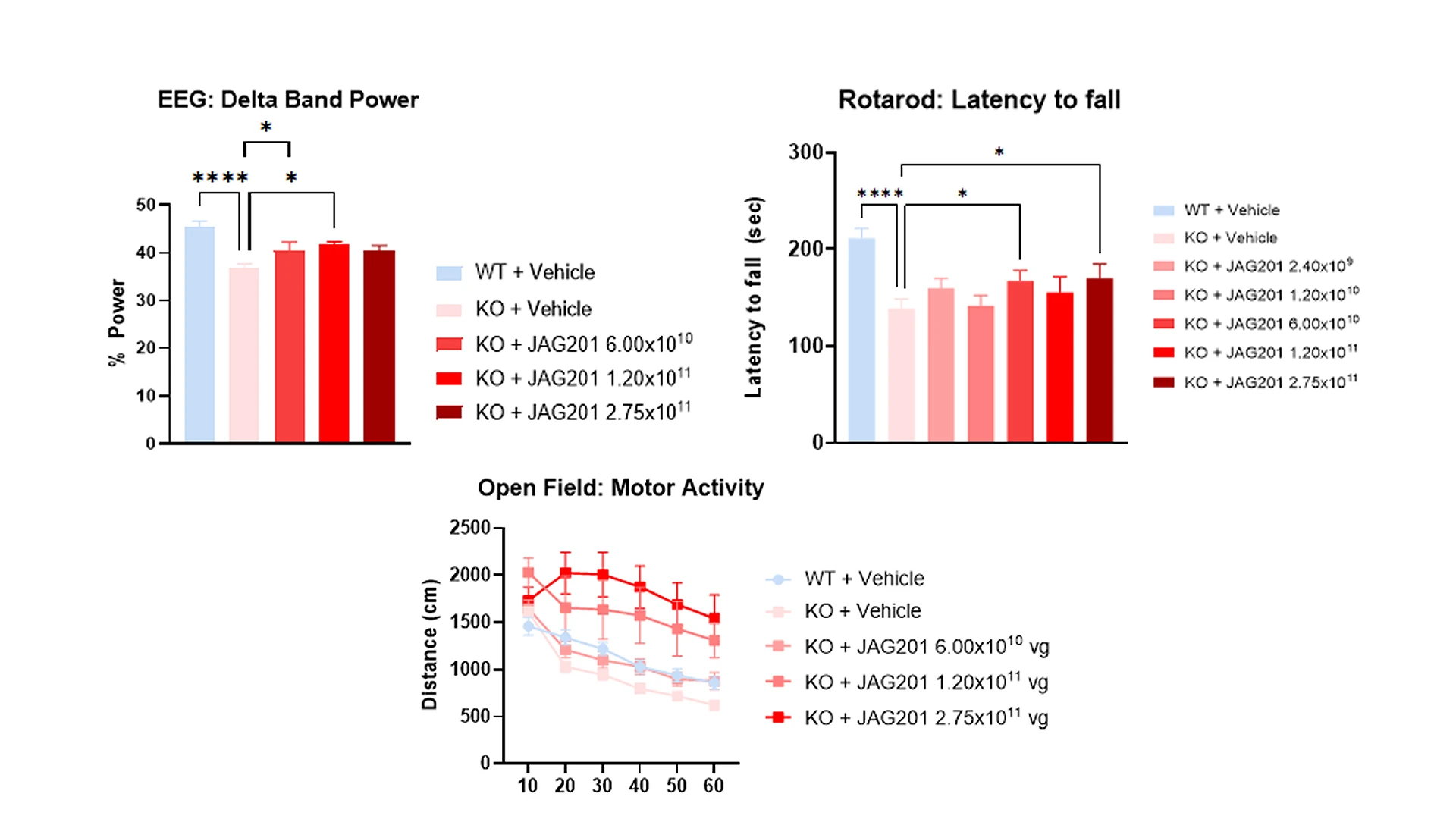

In mouse models of Phelan-McDermid syndrome, the delivery of JAG201 resulted in increased gene expression and evidence of behavioral changes. The researchers are hopeful the treatment could lead to measurable gains in cognition, language, sensory sensitivities, motor skills, and behavior for human patients.

While there is no placebo arm in the trial, the Seaver Autism Center, with its genetics-first approach to addressing ASD, has been collecting natural history data from patients with Phelan-McDermid syndrome for more than a decade, providing critical control data for comparison.

In mouse models of SHANK3 haploinsufficiency, mice treated with JAG201 saw increased gene expression, as well as improvements in sleep, motor function, and cognitive and behavioral outcomes.

“We now have data from several hundred patients as part of a national consortium to understand how Phelan-McDermid syndrome evolves. That important information allows for this type of research to take place,” Dr. Kolevzon says. “The fact that biotech companies are investing in these rare autism-related disorders is due, in part, to all of the work that the Seaver Autism Center at Mount Sinai has done over the past 15 years. We have natural history data, an engaged patient population, and the infrastructure to support these groundbreaking trials.”

Despite the uncertainties associated with testing a novel therapy, Dr. Kolevzon is excited to offer families a potential treatment for the first time. “Even the smallest amount of change in these kids can be dramatic for their quality of life. Small gains could be profound,” he says. “My hope is that we’ll see disease-modifying effects: Kids who will develop language, become toilet trained, and shift their trajectory closer to typical development.”

If the therapy shows promise, the methodology could also be adapted for other genetic forms of autism. “We’ve uncovered hundreds of autism-related genes, many of which affect overlapping pathways related to brain development,” Dr. Kolevzon says. “When I began working with these families, the idea of using gene therapy felt like science fiction. But now it’s quite real, and it’s incredibly gratifying to have something to offer families who have put their trust in us.”

Featured

Alexander Kolevzon, MD

Director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Clinical Director of the Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment