People living with addiction find themselves in a precarious world, where the brain assigns greater value to drug cues at the expense of healthier rewards, fueling their downward spiral. Mount Sinai has taken a major step toward unraveling that phenomenon through a first-of-its-kind neuroimaging study that used an Academy Award-nominated movie on heroin addiction as a stimulus for assessing drug cue reactivity in individuals with heroin use disorder (HUD).

The study, led by Rita Goldstein, PhD, the Mount Sinai Professor in Neuroimaging of Addiction at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, showed 30 inpatient participants with HUD and 25 healthy controls the first 17 minutes of Trainspotting, a movie with a narrative based on the lived experience of individuals battling heroin addiction.

The study, whose findings were published in Brain in May 2025, identified several regions of the brain that respond preferentially to drug cues in the movie. For participants with HUD, after three months of abstinence and treatment, these regions responded less, suggesting reduced craving. This discovery further suggested that a structured program of cognitive and behavioral therapy targeting those regions could be of great value, in addition to standard of care.

Unlike previous neuroimaging studies of addiction, which have used stock images as stimuli, the study by Rita Goldstein, PhD, uses a complex dynamic narrative—such as a real-life story—that has never been deployed before.

“In drug addiction, a drug-themed movie can function like a highly engaging mirror of a real-world drug environment in a way that static images can’t, evoking brain processes that are closer to the lived experience of the individual,” says Dr. Goldstein, senior author of the study.

A Novel Way to Assess Addiction

Previous neuroimaging studies of addiction have evaluated brain responses to repeated stock images of different types of stimuli, such as drugs, drug paraphernalia, food, or neutral stimuli such as household furniture. Dr. Goldstein’s tactic of using a complex dynamic narrative centered around the core symptoms of a particular psychiatric disorder had never been deployed before in studying a mental health disorder such as drug addiction.

“That technique thereby improves the ecological validity of our functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which we used to image the brain while participants watched the movie,” said Dr. Goldstein.

After the baseline fMRI scan and assessments, participants had a follow-up scan and interview 15 weeks later. During that time, patients with HUD received standard of care treatment, which included medications, relapse prevention and stress management, and group therapies.

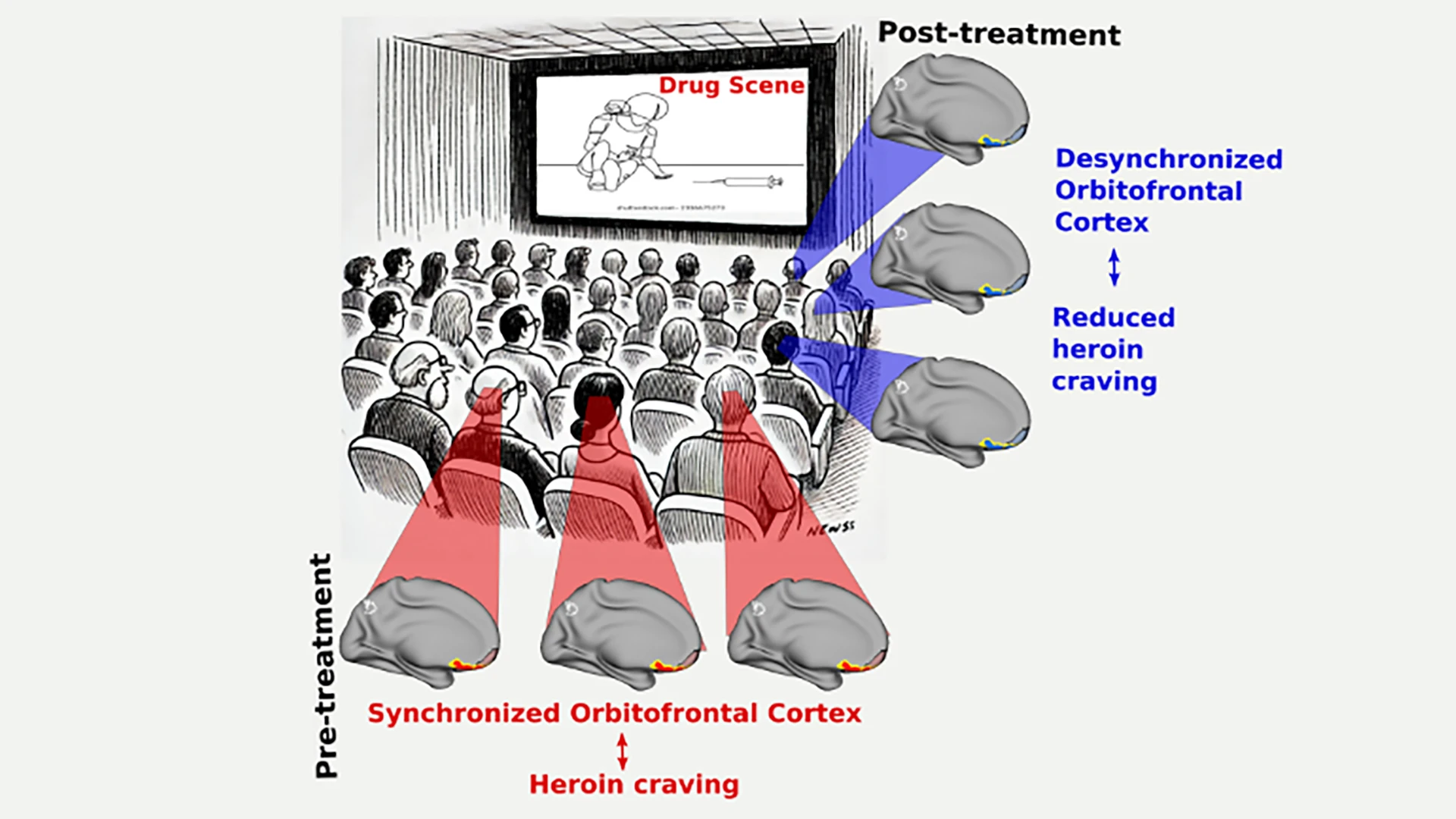

A graphical representation of the study: Prior to treatment, patients with heroin use disorder, when viewing scenes with drug cues from the movie Trainspotting, exhibited synchronized activity in their orbitofrontal cortex—displayed in red and yellow highlights. Post-treatment, the same brain regions of the patients showed a more desynchronized activity, which is correlated with reduced heroin craving.

Researchers found that for participants with HUD, several brain regions, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), responded to the movie in a way that was biased toward the drug content in the movie. Through this process, known as maladaptive salience attribution, the brain selectively focuses its attention on certain stimuli, such as drug cues, giving them a sense of enhanced importance as they outcompete other typical rewards and reinforcers—such as food, sex, and social connections—for attention and motivation.

In time, for people with substance use disorders, brain circuits adapt to the bias toward drug stimuli and contexts, creating a feedback loop that elicits further drug craving and compulsion to use drugs.

The team was highly encouraged when they discovered that brain regions, including the OFC, showed recovery from maladaptive salience attribution after treatment.

“Finding functional recovery in the OFC with just three months of treatment, with a link to reduced craving, was both surprising and noteworthy,” says Greg Kronberg, PhD, postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Psychiatry and first author of the study.

“The changes we observed in the OFC greatly enhance our understanding of addiction recovery at the cognitive level,” said Dr. Kronberg. “Moreover, we think these results can help in the development of cognitive-behavioral and neurophysiological interventions such as neurofeedback and electromagnetic brain stimulation to directly target brain physiology.”

Opening a New Window

The Mount Sinai team is developing a neurofeedback protocol in which study participants are shown their brain activity in real time, with the goal of training them to modulate activity toward a target value and thereby facilitate recovery in people with substance use disorders.

The scientists are also studying the use of other movies, similar to Trainspotting, that offer a naturalistic drug cue reactivity platform, where one goal is to test for menstrual phase differences in women with addiction.

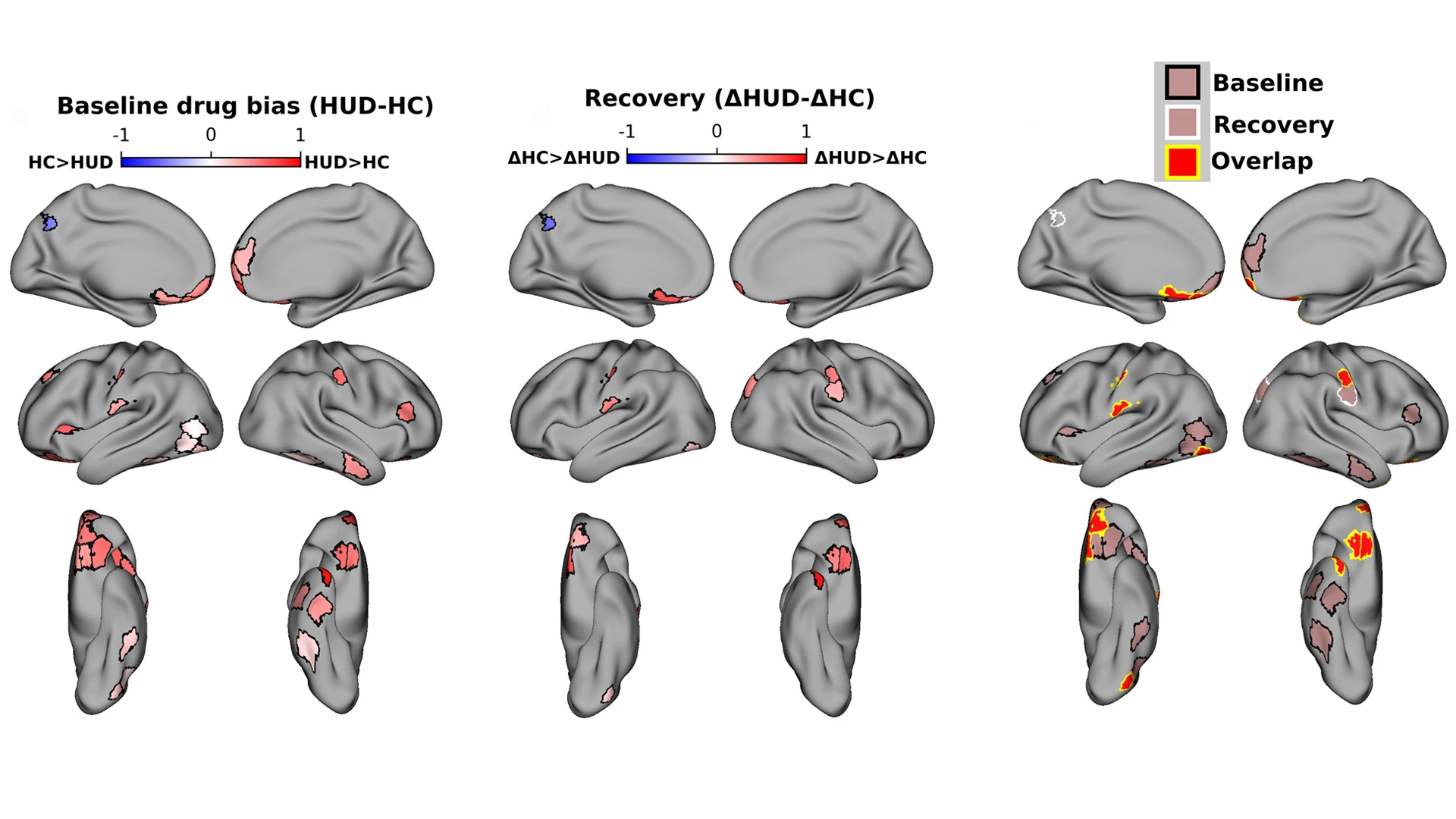

Participants with heroin use disorder were given a baseline fMRI scan prior to treatment, and the drug-biased responses in the brain were noted (left). Following treatment, the same participants were scanned again for drug-biased responses (center). Researchers saw not only a decrease in drug-biased responses, but also recovery in other brain regions (right).

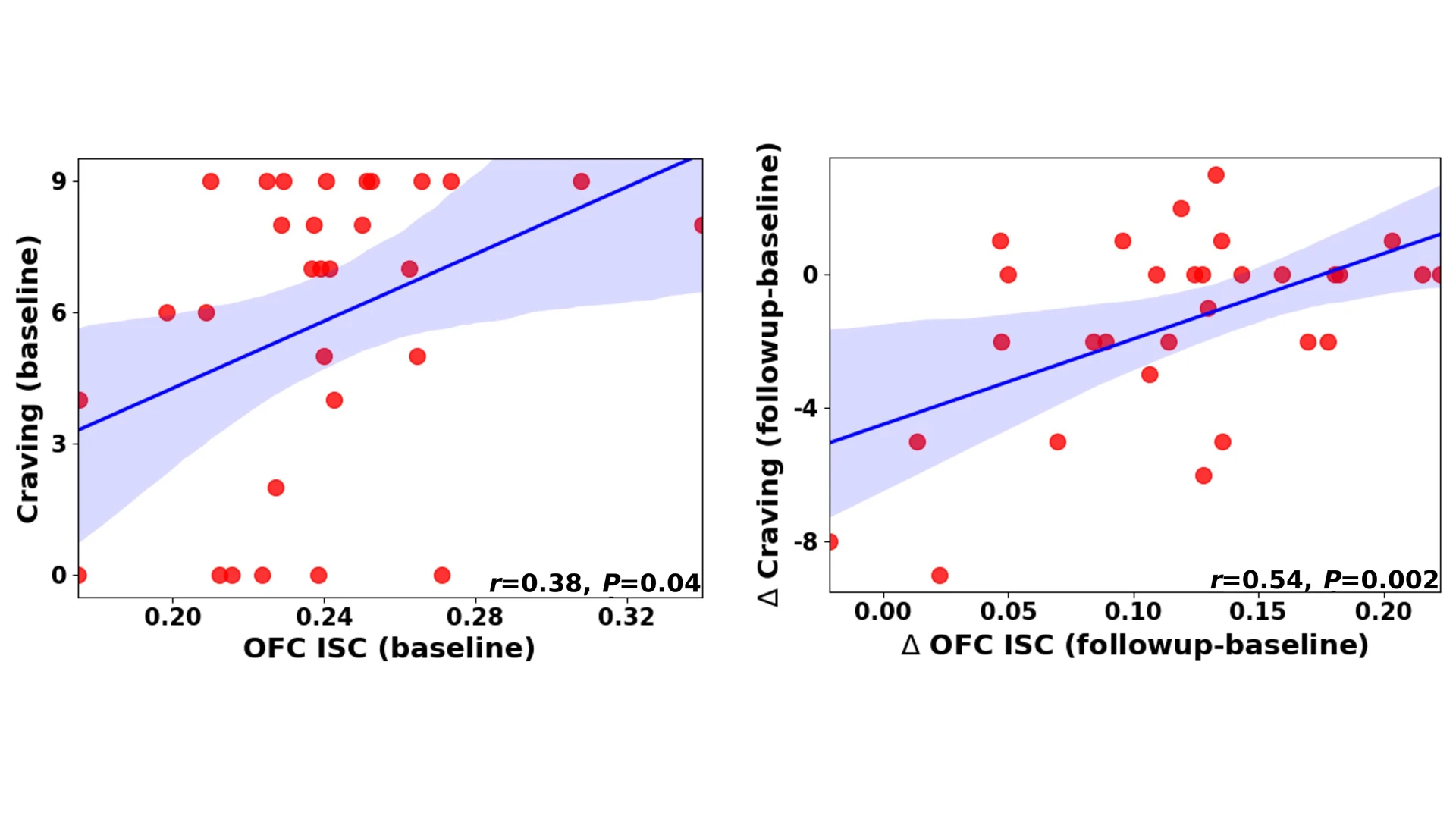

The left scatterplot graph shows the inter-subject correlation between orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) activity and craving for participants with heroin use disorder at baseline. The right shows parallel delta changes in OFC activity and craving between sessions, with many points demonstrating downward shift in deltas.

A major challenge, however, is that natural rewards may be more complex and difficult for humans to acquire and may have dynamics that develop across longer time frames. This is especially so compared to drugs that have immediate and clear effects on both the underlying neurobiological substrates and subjective perceptions of drug effects (i.e., drug highs).

Still, Dr. Goldstein and her team think they have opened an important new window not just for studies in human drug addiction, but other psychopathologies. “If further adopted in other disorders such as depression and PTSD,” says Dr. Goldstein, “this methodology could greatly enhance the mechanistic study of higher-order cognitive-emotional neural processes that are uniquely expressed in people with various disease processes.”

Featured

Rita Goldstein, PhD

Chief of Neuropsychoimaging of Addiction and Related Conditions Program; Mount Sinai Professor in Neuroimaging of Addiction

Greg Kronberg, PhD

Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Psychiatry