When Mount Sinai researcher James Murrough, MD, PhD, heard that ezogabine—the first and only therapeutic agent that targets the KCNQ2/3 potassium channel in the brain for partial-onset seizures—was being withdrawn from the market for commercial reasons in July 2017, he knew he had to act fast.

At the time, Dr. Murrough was preparing to launch a National Institutes of Health- (NIH) funded randomized clinical trial to assess ezogabine’s impact on reward circuit activity and clinical symptoms in depression. Available preclinical and clinical data, which led to the NIH grant, suggested that the KCNQ channel could be a novel target for the treatment of depression, but in the absence of placebo-controlled human trial results, it was not possible to predict whether this approach would be successful.

The only way he could proceed with the study was to purchase all available supplies nationwide. Against the odds, he managed to secure enough ezogabine to administer 900 milligrams a day for five weeks to a cohort of 45 patients—an effort that yielded remarkable positive outcomes. Treated patients showed significantly larger improvements versus the placebo cohort in their symptom scores, such as the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale.

James Murrough, MD, PhD, with Sara Hameed, clinical research coordinator.

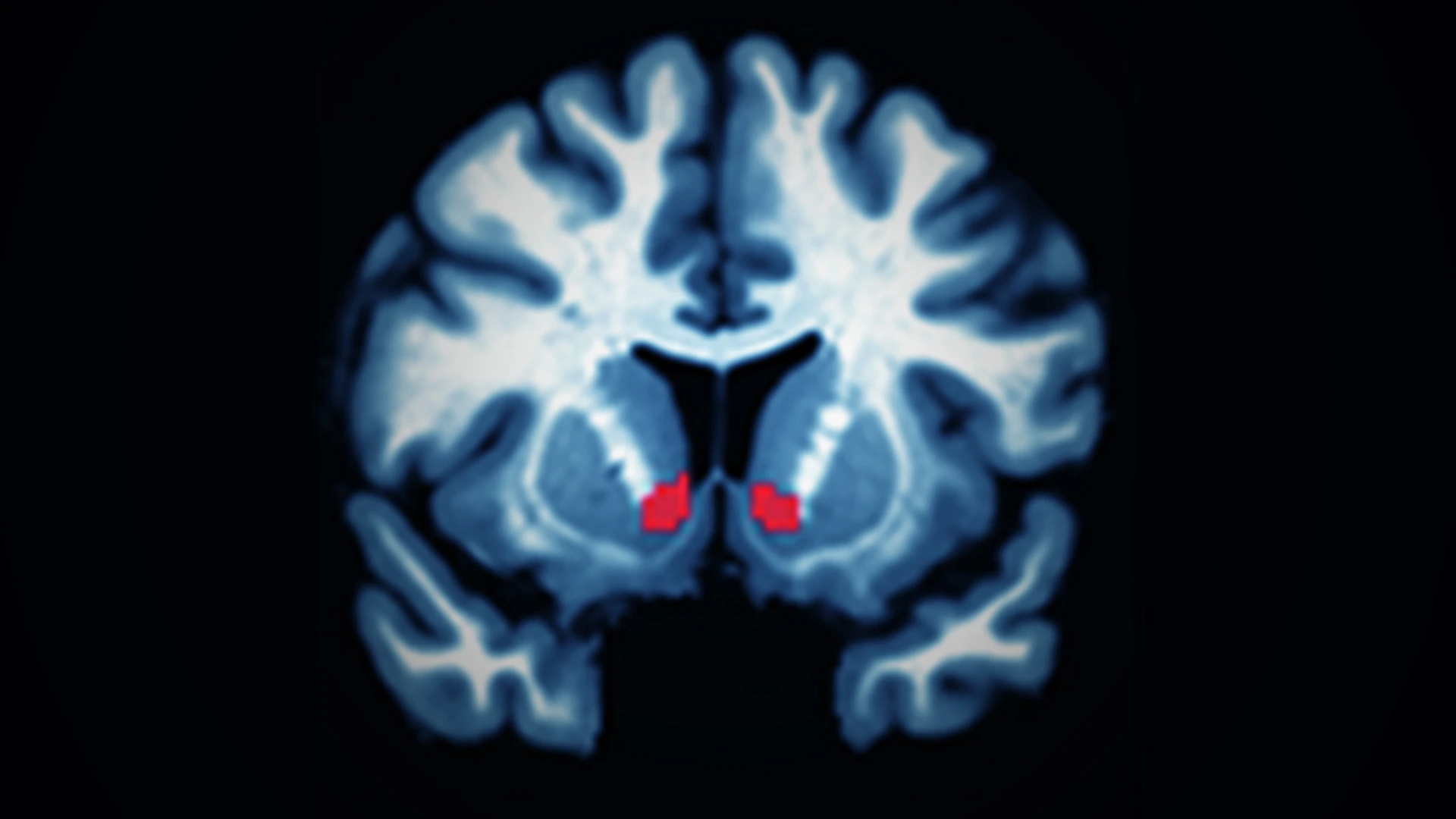

Surprised to see such an impact on multiple clinical outcomes relevant to depression, Dr. Murrough considered the trial a success on a clinical level. Although the study’s primary neuroimaging endpoint—the numerical increase in ventral striatum response to reward anticipation—showed a trend towards separation between active and placebo, it did not reach statistical significance between the two cohorts.

“It would be ideal to demonstrate target engagement because that is important for the progress of science,” says Dr. Murrough, Professor of Psychiatry, and Neuroscience, and Director of the Depression and Anxiety Center for Discovery and Treatment at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “But if you ask patients which is more important—that their brains demonstrated a specific signal or that they are experiencing relief from their symptoms of depression—they will say it is symptom relief.”

An Accidental Clinical Outcome

Dr. Murrough had not intended to demonstrate clinically that ezogabine improves symptoms of depression; instead, he was testing a hypothesis that the KCNQ family of potassium channels offers a valid target for treating patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). It is estimated that one in three patients diagnosed with MDD—a leading cause of disability worldwide according to the World Health Organization—is not responsive to existing therapeutics. By exploring the molecular mechanisms involved in depression, Dr. Murrough hopes to identify therapeutic targets, such as KCNQ, that differ from existing treatments and have the potential to be game changers.

Dr. Murrough’s interest in KCNQ builds upon previous research conducted by Mount Sinai researchers. It was Ming-Hu Han, PhD, Professor of Neuroscience, and Pharmacological Sciences, at Icahn Mount Sinai, who first identified the potential of these channels, based on research initiated by Eric J. Nestler, MD, PhD, the Nash Family Professor of Neuroscience, Director of The Friedman Brain Institute, and Dean for Academic and Scientific Affairs at Icahn Mount Sinai, and Chief Scientific Officer of the Mount Sinai Health System.

In a study involving a social defeat stress model, Dr. Han noted that mice that did not show depressive behavior naturally exhibited increased expression of KCNQ receptors in their brains. He subsequently showed that when these channels were blocked, the mice became depressed. Based on those findings, Dr. Han looked at the impact of activating these channels by injecting a class of compounds known as positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) directly into the reward circuits of mice that exhibited depressive behavior.

“PAMs are known to bind to KCNQ receptors and cause them to stay open, effectively functioning as if there are more of them,” Dr. Murrough explains. “Overall, these therapeutics are known to calm brain cells.” Dr. Han found that mice that exhibited signs of depression paradoxically had an overactive reward circuit wherein the dopamine cells were on overdrive. The hypothesis is that they are not responding to environmental cues and stimuli, which leads to behavioral depression. “Dr. Han showed that if you use PAMs to open the KCNQ channels in the reward circuit, it has an antidepressant effect,” Dr. Murrough says.

Finding a Path Forward

What Dr. Murrough observed in his study, which was published in The American Journal of Psychiatry in March 2021, mirrored Dr. Han’s findings. Although he concluded KCNQ warranted further research, the withdrawal of ezogabine made further work with the compound unviable. That changed in 2019 when Dr. Murrough discovered that a Vancouver-based company, Xenon Pharmaceuticals, had developed a more selective, better-tolerated KCNQ channel opener, XEN1101, which was undergoing human clinical trials for efficacy in treating seizure disorders, and had shown promising preclinical results in animal models of depression.

Dr. Murrough engaged the company and is now in year one of a three-year randomized control trial that will explore the impact of this pharmaceutical agent on adults with major depression. The study will enroll 60 patients, half of whom will be administered two 10-milligram capsules of XEN1101 each day for eight weeks. Neuroimaging and symptom effects from this cohort will be compared against those from the placebo cohort. In parallel, Xenon is conducting a proof-of-concept trial using clinical endpoints to measure an improvement of depressive symptoms in approximately 150 subjects.

Dr. Murrough with Sara Hameed, clinical research coordinator.

Replicating the symptom improvements observed in the previous study or achieving statistical significance in neuroimaging findings in the ongoing trial would be exciting, Dr. Murrough says. Either outcome would provide compelling evidence that KCNQ is a worthwhile therapeutic target for pharmaceutical development. There is also the possibility that the study will provide insights for predicting which patients are more likely to respond to KCNQ channel openers.

“That is an important future direction for us—not just exploring the efficacy of these therapeutics but also the opportunity to examine why they perform better among certain patients,” he says. “That would open the door to more personalized medicine approaches. Regardless, the more we know about the brain, the more likely we are to move the needle in terms of identifying or developing effective treatments for patients who have this debilitating illness.”

Note: Neither Dr. Murrough nor Mount Sinai has any financial interests in Xenon Pharmaceuticals. However, Dr. Murrough is an inventor on a pending patent application filed by Mount Sinai for the use of KCNQ channel modulators for mood disorders and related conditions. If KCNQ channel activation is shown to be an effective treatment for depression, both Mount Sinai and Dr. Murrough (as a faculty inventor) could benefit financially.

Featured

James Murrough, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry, and Neuroscience; Director of the Depression and Anxiety Center for Discovery and Treatment