Every day, the human brain makes a series of computations that enable us to learn and adapt to new social situations. At Mount Sinai’s Center for Computational Psychiatry, Xiaosi Gu, PhD, is interested in the psychiatric ramifications of breakdowns in those computations.

“Many psychiatric disorders are associated with problems with how the software of the brain is programmed to handle complex situations, such as social interactions,” says Dr. Gu, Director of the Center, and Associate Professor of Psychiatry, and Neuroscience, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Her team isdeveloping paradigms and models that can capture real-life social behaviors among healthy individuals and those who have a psychiatric diagnosis. This enables better understanding of the neurocomputational mechanisms at play in those behaviors and how any alternation in those mechanisms can contribute to mental health symptoms. Findings from their efforts were published October 29, 2021 in eLife.

Dr. Gu is applying a combination of neuroscience, cognitive science, and behavioral economics expertise to explore how our beliefs, emotions, decision-making, and social interactions are affected by these mechanisms in states of mental health and illness. She is particularly interested in “social controllability”—the degree of control we have over our relationships—in the context of mental health. This research has become more vital given the impacts of COVID-19 and other issues such as global warming and geopolitical challenges on mental health.

“The social world we live in has become more chaotic,” Dr. Gu explains. “Many of the core symptoms or triggers of mental health issues stem from the sense that we have too little—or too much—control over our lives or relationships.”

The Illusion of Control

Using large-scale digital phenotyping, computational modeling, and neural recording, Dr. Gu and her research team have launched studies on how the human brain encodes social information and how that might affect mental health.

In one study, they explored whether people used forward thinking in situations to try to influence others or exert “social control.” Forty-eight participants played different versions of the “ultimatum game,” a well-known bargaining exercise in which the subjects are asked to split $20 with an opposing team. In one “controllable” version of the game, participants could affect the amount of money they were offered in each round. In the “uncontrollable” version of the game, participants were offered a random amount each round.

Xiaosi Gu, PhD, and her team members.

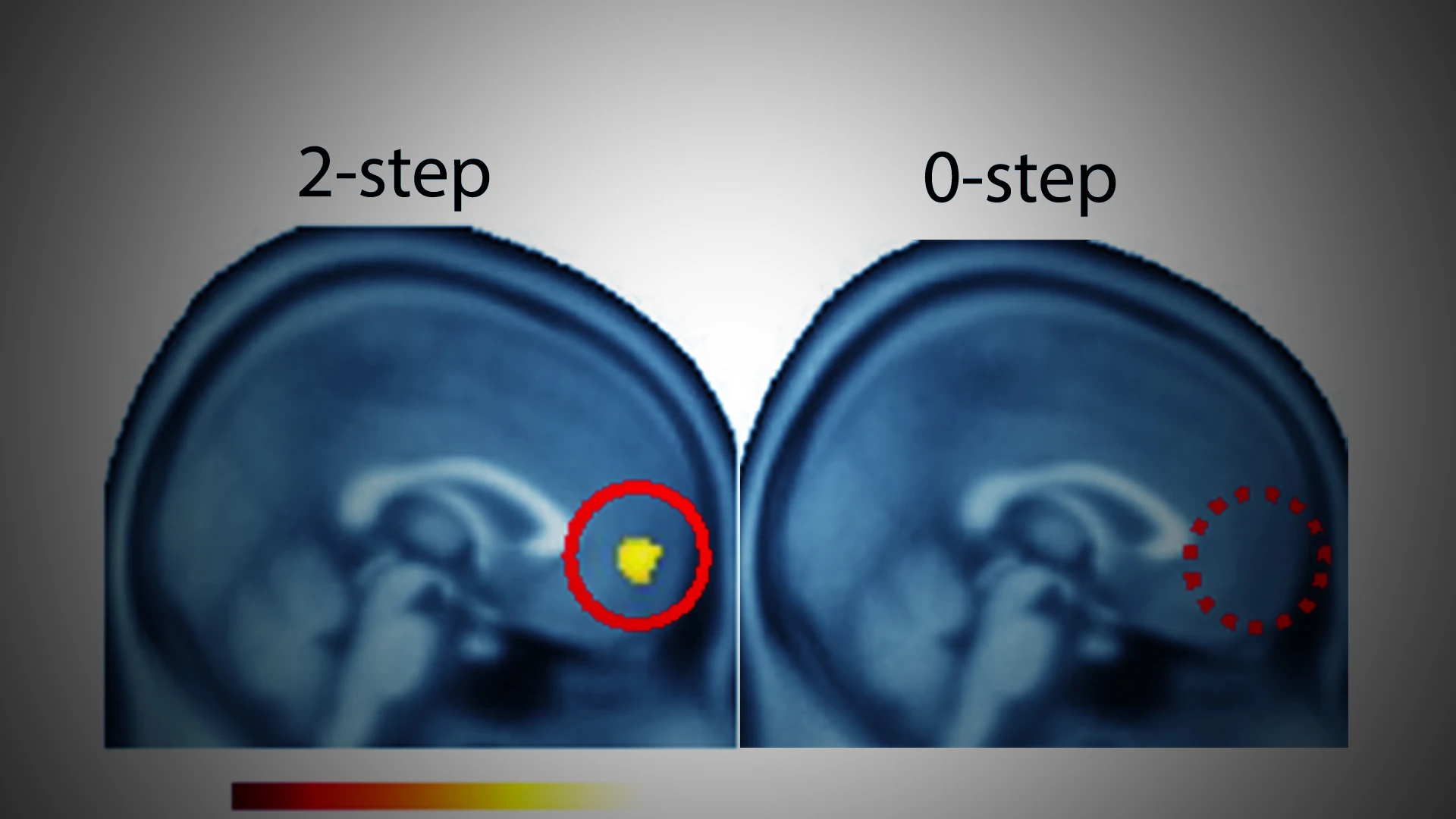

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, Dr. Gu observed that the choices made by the study’s participants were driven by neural activity in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex—a decision-making center that is known to be involved in forward thinking. This, she says, suggests that the participants were able to think a few steps ahead in social interactions. Interestingly, participants reported a sense of control even during the “uncontrollable” version, beyond what they actually had. In a subset of participants who played games against a computer instead of teams, the reported sense of control was 60 percent regardless of the version or the fact they received higher offers in the “controllable” version.

The initial study involved healthy controls to establish social controllability as a paradigm and the neural mechanism involved. A subsequent study involving people with a high sense of delusion further explored the mental health relevance of social controllability.

Daniela Schiller, PhD, and Dr. Gu.

Dr. Gu and members of her lab.

In the latter study, Dr. Gu observed that people with a high degree of delusion were able to influence their partners in controllable interactions just as well as participants without delusion. But individuals with a high degree of delusion both attempted to exert control and reported a higher sense of control in situations that were uncontrollable, suggesting they had an illusion of control.

“We knew that illusory beliefs were central to delusion, but did not know how they came about,” Dr. Gu says. The study provided initial proof that there was a mismatch between the controllability of the environment and how people perceive such controllability in delusion. But the only way to truly understand the causal effect between delusion and those mental computations requires longitudinal studies, she says.

Dr. Gu is conducting similar studies among cohorts with drug addiction, eating disorders, personality disorders, and autism spectrum disorders. She is also interested in applying her social cognition paradigms to assess the efficacy of treatment through neuromodulation—an interest that has led to several collaborations with Helen Mayberg, MD, founding Director of the Nash Family Center for Advanced Circuit Therapeutics at Mount Sinai and Mount Sinai Professor in Neurotherapeutics.

“Although neuromodulation is currently limited to a small percentage of the patient population, given that it involves brain surgery, it offers a unique opportunity for us to understand the direct, causal relationship between neurobiology and behavior,” Dr. Gu says. “This will eventually help us design better evidence-based treatment for all patients based on their individual biology and needs.”

Featured

Xiaosi Gu, PhD

Associate Professor of Psychiatry, and Neuroscience; Director of the Center for Computational Psychiatry