Acute myocarditis (AM) is a medical condition in which there is inflammation of the heart muscle, often leading to cardiac dysfunction. It affects children and adults, who can present dramatically with heart failure. Treatment is supportive, not curative. Outcomes vary widely, ranging from complete recovery to heart transplantation or death.

The list of causes of AM is long, but viral infections are generally understood to be the precipitating events. Figuring out exactly which virus underlies each of the particular cases is enormously challenging. People with AM seemingly present after the acute infection and, even when heart tissues are tested, identification of the virus is often not possible. That said, the viruses causing AM seem to be common ones that generally result in typical mild infections.

This raises intriguing questions: Why do some children experience severe AM when other children infected with the same virus have routine illness? Do children with severe AM have an underlying susceptibility that creates risk?

To address those questions, two Mount Sinai physician-scientists, Bruce Gelb, MD, Gogel Family Professor and Director of The Mindich Child Health and Development Institute, and Dean for Child Health Research, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Amy Kontorovich, MD, PhD, Associate Professor of Medicine at Icahn Mount Sinai, have teamed up to study patients with AM from a human genetic perspective. They work closely with the team at Mount Sinai Children’s Heart Center, in partnership with Mount Sinai Heart, translating research findings into more targeted care for patients.

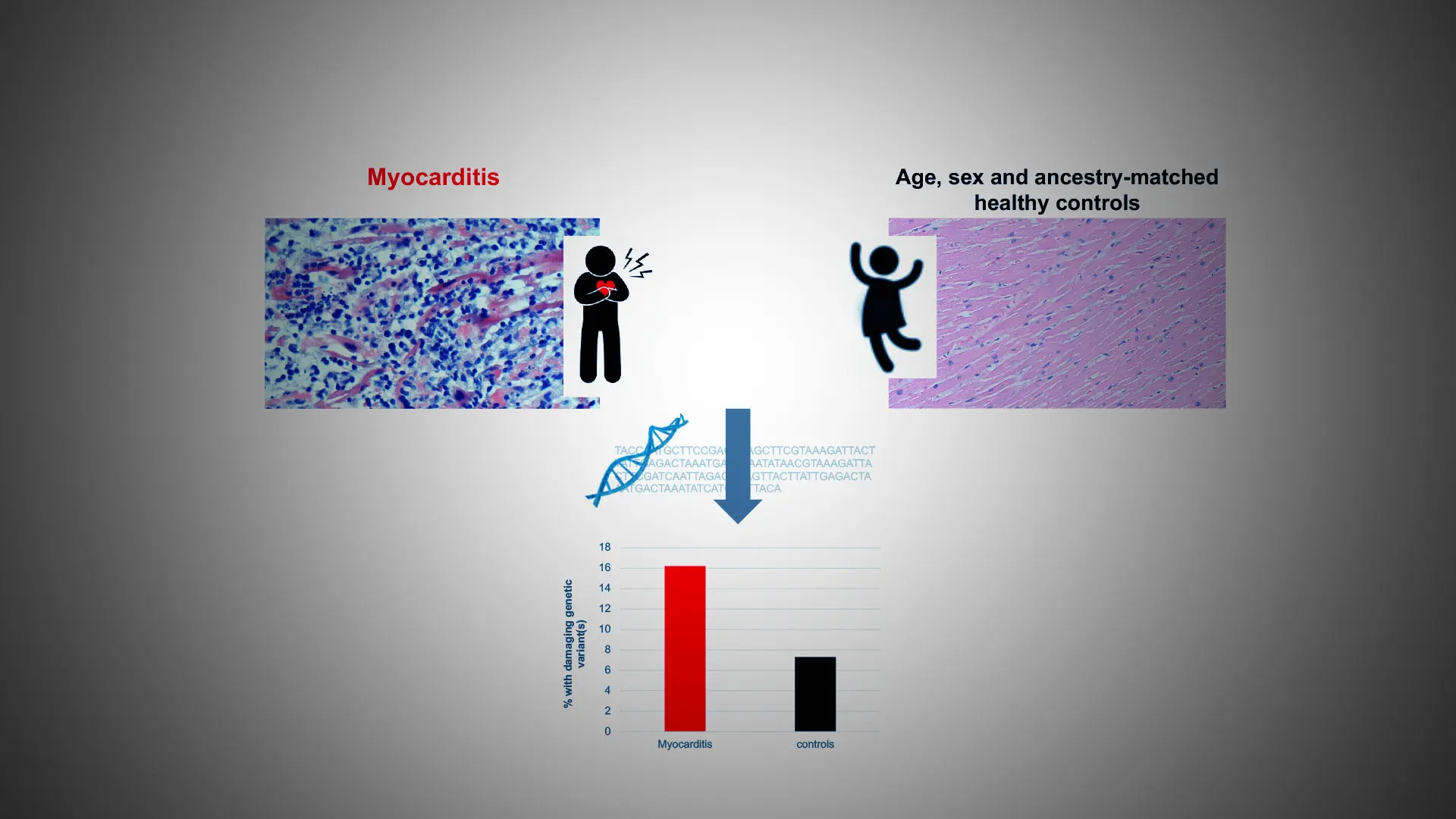

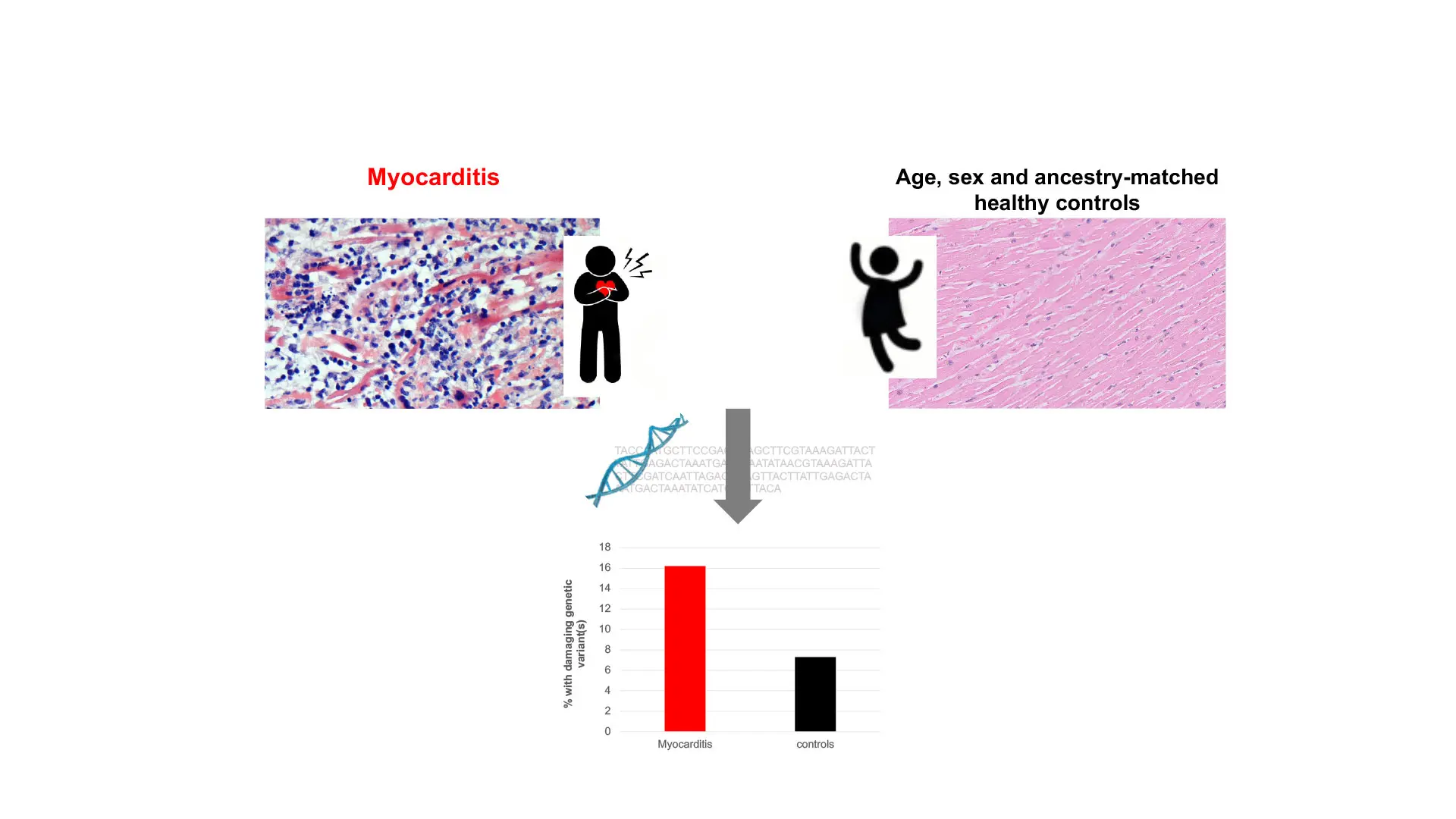

Their first study, in collaboration with Jean-Laurent Casanova, MD, PhD, a leading expert on inborn errors of immunity at Rockefeller University, found no defects in genes related to the immune system in children with AM. Rather, they discovered that pediatric patients with AM were far more likely to have damaging genetic variation in genes underlying cardiomyopathies.

In the past year, Drs. Kontorovich and Gelb have published the results of two additional studies of AM. For the first of those, they worked with investigators at the Office of the Medical Examiner of the City of New York to study cardiomyopathy genes in children who had died from AM. This study had the advantage that the diagnoses of AM were ironclad since the decedents’ hearts had been examined microscopically. As in the study conducted in collaboration with Dr. Casanova, a burden of damaging genetic changes in cardiomyopathy genes was observed. Finally, they teamed up with investigators in Germany and in Memphis, Tennessee, to analyze DNA samples from adult and pediatric patients with AM. As in the first two studies, predisposing genetic variation was observed.

Overall, Drs. Gelb and Kontorovich have discovered that about 15 percent of patients with AM have a demonstrable genetic predisposition for the condition. As often happens with research, this has led to more questions: Do individuals harboring cardiomyopathy genetic variants present with AM because their hearts cannot handle the stress of a common viral infection in the heart muscle? Or does the presence of genetic changes make it easier for common viruses to infect and then damage heart muscle? Drs. Kontorovich and Gelb hope to address these and other issues through their ongoing research. For now, their work has clear clinical importance: patients presenting with AM need genetic testing and, when positive, testing should be expanded to at-risk family members.

Groundbreaking studies at Mount Sinai have shown that patients presenting with acute myocarditis (AM), presumably precipitated by viral infections, are more likely to harbor damaging variants in cardiomyopathy genes than ancestry- and age-matched controls. This shows that AM can arise due to a predisposition in the host.

Featured

Bruce D. Gelb, MD

Gogel Family Professor of the Child Health and Development Institute

Amy Kontorovich, MD, PhD

Associate Professor of Medicine (Cardiology, Medical Genomics)