In the following Q&A, Dr. Sanders highlights some of her groundbreaking research into

environmental exposures during critical windows of kidney development in the fetal, infant, and childhood stages that may lead to chronic disease.

Q. What are some of the greatest environmental risk factors today to maternal and child kidney health, and how much do we know about the nature and prevalence of these exposures?

Dr. Sanders: Air pollution, metals, cigarette smoke exposure, phthalates, and others are common environmental risk factors, though estimates regarding how much each contributes to maternal/child health are not widely reported (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29884847/; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28727988/). What we do know is that these

exposures are ubiquitous and concomitant. Some estimates suggest that up to 26%

of kidney diseases in high-risk populations may be attributable to environmental factors. Studies show, for example, that 12% percent of hypertension in adults is attributable to ambient PM2.5 exposure, and that 3% to 19% of high blood pressure may be attributable to metals, arsenic, and phthalates exposure.

“Some estimates suggest that up to 26% of kidney diseases in high-risk populations may be attributable to environmental factors.”

- Alison P. Sanders, PhD

Q. How early can “critical windows of susceptibility” develop in humans, and how long before they result in cell death and functional changes in renal cell lines?

Dr. Sanders: This question actually mixes two concepts: windows of susceptibility in human development and cell-based toxicity studies. While these lines of work are parallel, we cannot directly interpret them in the same context. In the context of human development, windows of susceptibility can occur when there is a time of rapid development that is vulnerable to toxic exposures. When the timing of harmful exposure coincides with the timing of vulnerable development potentially resulting in an adverse outcome, we’d call that a critical window of exposure. My lab and others are interested in how this overlap influences subsequent health outcomes.

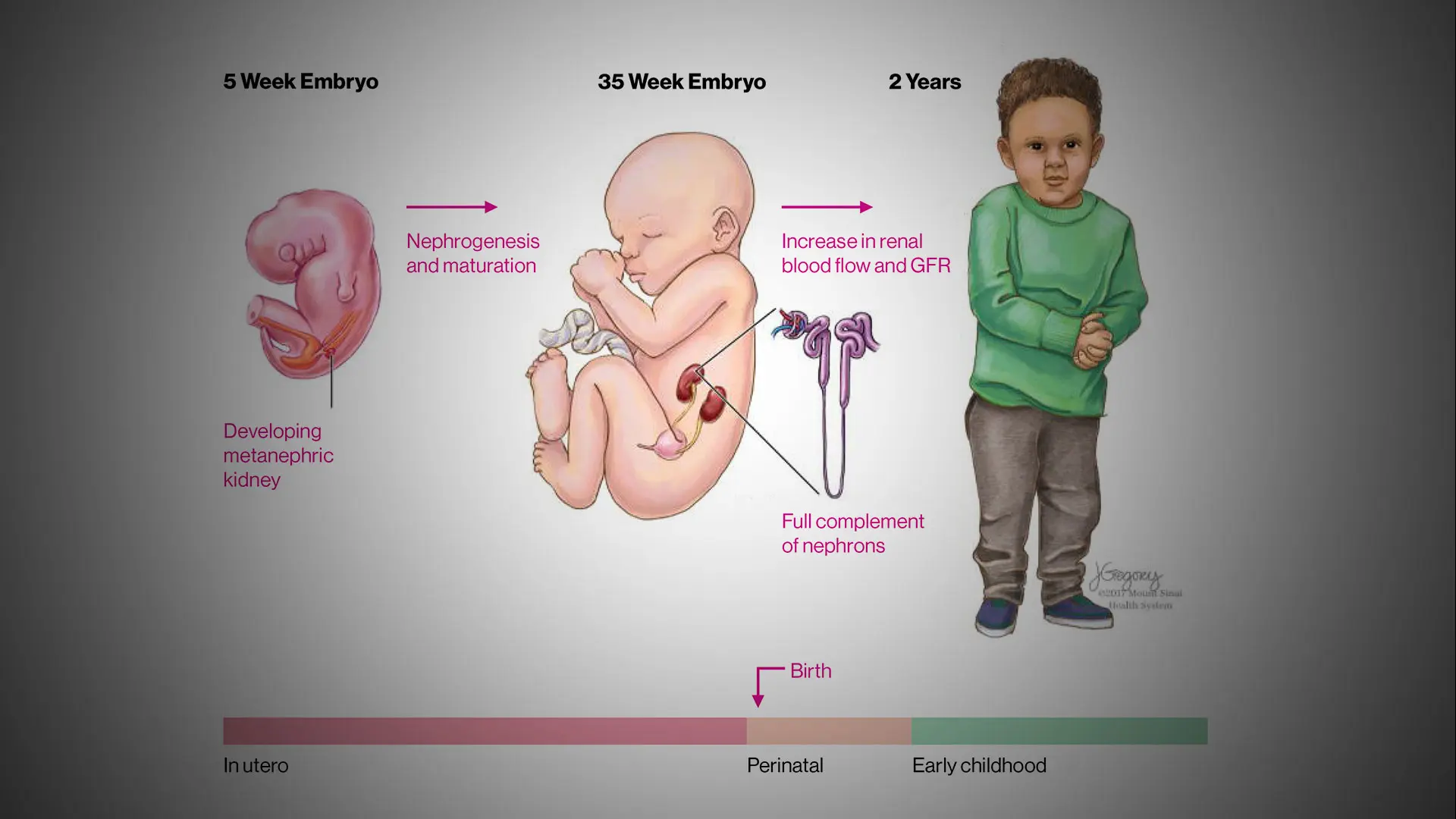

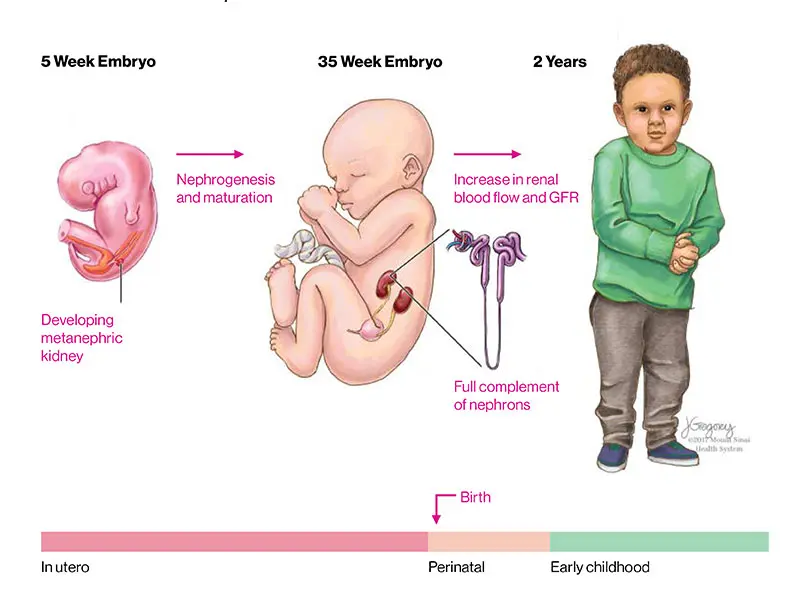

For example, several of my ongoing studies suggest that toxicant exposures

during the second and third trimesters—the critical biological windows of kidney

nephron and tubule formation—as well as postnatal exposures, may influence

kidney function or blood pressure as early as preadolescence (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33036323/; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31881529/; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30145310/). Small shifts in childhood or adolescent

kidney function or blood pressure trajectories may set individuals down a path to development of kidney disease or hypertension in adulthood (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31326826/; https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31402058/). More studies are needed to identify these early life environmental risk factors, as well as the timing of when exposure prevention may be most critical in combination with traditional well-established risk factors.

Q. Describe how your laboratory is developing new models to assess

environmental risk factors during fetal, infant, and childhood development.

Dr. Sanders: My lab is collaborating with experts in renal cell physiology and developmental biology to examine how the timing of exposures affects kidney cell or organ

development and maturation in a controlled laboratory setting. We are exploring specific mechanisms regarding critical timing of development and environmentally relevant mixtures of toxicants that might cause altered cell functions, kidney injury, or altered growth and development, ultimately leading to impaired kidney function.

The timing of exposures to environmental chemicals during periods of renal development from embryogenesis to birth and through childhood can inform critical windows of kidney susceptibility. ©Mount Sinai Health System

Q. How could your investigations into environmental risk reshape the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic kidney disease?

Dr. Sanders: While some of the pathobiology leading to chronic kidney disease remains unclear, we understand that the process is complex and, like many chronic diseases, begins long before clinical diagnosis. My research investigates how the environment and mixtures of environmental chemicals/toxicants interact with traditional risk factors such as obesity, preterm birth, and nutritional status to hasten or prevent chronic kidney

disease (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31891650/; Saylor C, Tamayo-Ortiz M, Pantic I, McRae N, Estrada-Gutierrez G, Parra-Hernandez S, Tolentino MC, Baccarelli AA, Gennings C, Satlin LM, Wright RO, Tellez-Rojo MM, Sanders AP. Prenatal blood lead levels

and reduced preadolescent glomerular filtration rate: Modification by body mass

index. Accepted Dec 2020: Environment International.). Indeed, inasmuch as these factors are intervenable, they could lead to prevention, earlier diagnosis, or monitoring of susceptible populations. Our laboratory-based work will also help to better understand the

mechanisms of toxicant-altered kidney development and maturation that may

ultimately help inform treatment and therapeutics development: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32166731/ Levin-Schwartz et al., 2021.

Q. How can we prevent exposures that might set people on a path to kidney

disease beginning early in their lives?

Dr. Sanders: We must continue to biomonitor pregnant women and children for toxic exposures, and reduce exposure when levels are elevated. However, while blood lead levels

are monitored at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guideline value of 5 ug/dL, there is no safe level of lead. Biomonitoring of other toxic exposures—such as to particulate matter air pollution, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, and organic chemicals—will continue to shed light on complex low levels of mixtures we are exposed to daily. Translational risk assessments of the nephrotoxic effects of population-relevant mixtures, applied in vitro and in vivo, are a key first step to understanding the mechanisms

underlying populations at increased risk for later-life kidney disease development.

Q. What role can physicians play in heightening the public’s awareness of environmental exposures to children’s health, and strategies to build a healthier environment?

Dr. Sanders: Mount Sinai’s Transdisciplinary Center on Early Environmental Exposures, of which I am a member, offers guidance and support here by fostering communication and

collaboration between health professionals and the community. The Center’s

website (http://tceee.icahn.mssm.edu/community-engagement-core/) provides helpful details.

Featured

Alison P. Sanders, PhD

Assistant Professor, Pediatrics, and Environmental Medicine and Public Health, and Director of the Environmental Nephrotoxicology Laboratory