Mount Sinai’s Sports Medicine Service offers the most cutting-edge operative and nonoperative joint preservation techniques available today to delay or potentially even eliminate the need for joint replacement.

In 2022, surgeons in Mount Sinai’s Orthopedics Division of Sports Medicine were among the first in the country to perform anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) repairs using the Bridge-Enhanced ACL Restoration (BEAR)® Implant, a new alternative to the traditional graft reconstruction for torn ACLs that is improving patient outcomes.

Mount Sinai’s sports medicine surgeons also use a variety of advanced cartilage repair techniques, including orthobiologic injections and matrix-associated autologous chondrocyte implantation (MACI) in the knee and other joints.

“Our goal is to preserve joints by keeping ligaments and cartilage intact. We aim to restore function, prevent arthritis, and reduce the likelihood for a knee replacement,” says Shawn G. Anthony, MD, Associate Chief of Sports Medicine for the Mount Sinai Health System and Assistant Professor of Sports Medicine and Orthopedic Surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“The idea,” according to James N. Gladstone, MD, Chief of the Sports Medicine Service and Associate Professor of Orthopedics at Icahn Mount Sinai, “is either to help give the tissue a jump-start to repair itself, or to create a better environment to take the pain away and hopefully prolong the life of the natural joint longer while giving people function.”

Bridging the Gap: BEAR Implant Restores the Native Ligament

According to studies, approximately 400,000 ACL tears happen every year in the United States. Traditional surgical repair involves removal of the torn ACL tissue and reconstruction, either from a patient’s own tissue (autograft) or cadaver tissue (allograft). While often successful, this procedure fails to fully restore function in up to 20 percent of patients, say Drs. Anthony and Gladstone, particularly among those under 20 years old, and the autografts can damage the harvest site and can lead to muscle deficits based on which tendon is used.

Granted marketing authorization under the De Novo premarket review pathway by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in December 2020 to treat complete ACL ruptures among patients who are at least 14 years old, the BEAR Implant is currently the only available alternative to reconstruction with allograft, autograft, or suture-only ACL repairs. It does not require harvested tissue, but instead is made from a decellularized, bovine-derived, type 1 collagen that resorbs within eight weeks of implantation.

“The BEAR Implant ACL repair is one of the most exciting new developments in our field. It’s a new technique by which we can help the torn ends of the ACL heal back together. It’s the first success story in regenerative medicine for ACL injury,” says Dr. Anthony.

The actual BEAR Implant “looks like a large marshmallow that is soaked with the patient’s own blood. It works as a scaffold that helps bridge the gap between the torn ends of the ACL,” he explains.

A surgeon prepares a BEAR Implant prior to surgery.

It’s approved for a range of ACL tear types, including proximal and distal avulsions, based on level 1 clinical evidence of improvement in pain and function.

Dr. Anthony’s first BEAR Implant was in March 2022, and that patient continues to do well 20 months out. Drs. Anthony and Gladstone together have performed more than 30 additional procedures at Mount Sinai since then, among the highest volumes in the United States. All have had good results thus far.

“I’ve had patients who had traditional ACL reconstruction in prior years and then tore their ACL on their other leg. They uniformly say they prefer the BEAR Implant and have higher satisfaction, that the BEAR Implant ACL-repaired knee feels more natural, and they experienced less painful surgery than the traditional ACL reconstruction,” Dr. Anthony says.

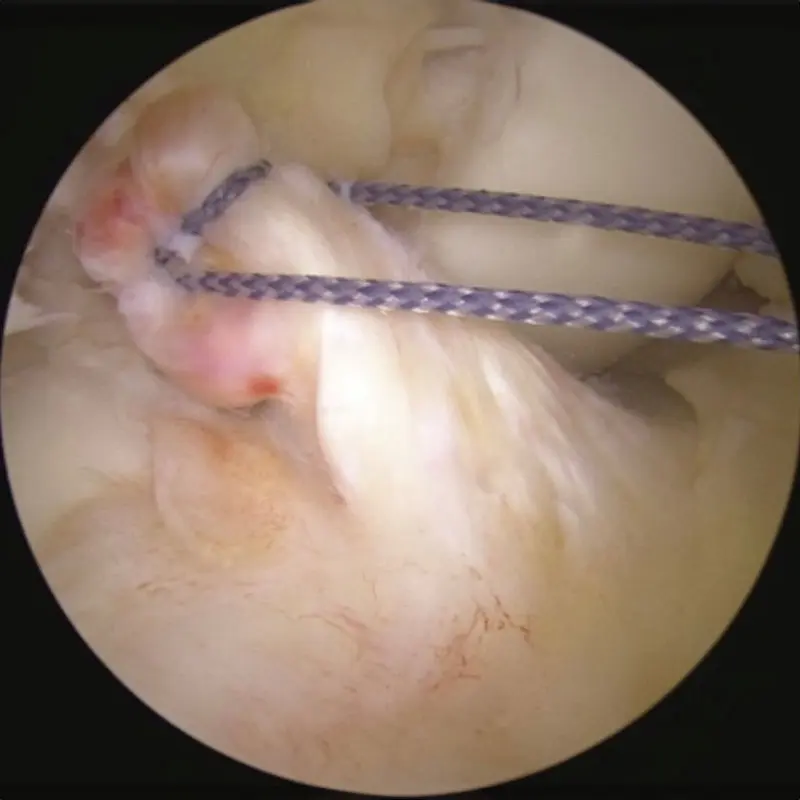

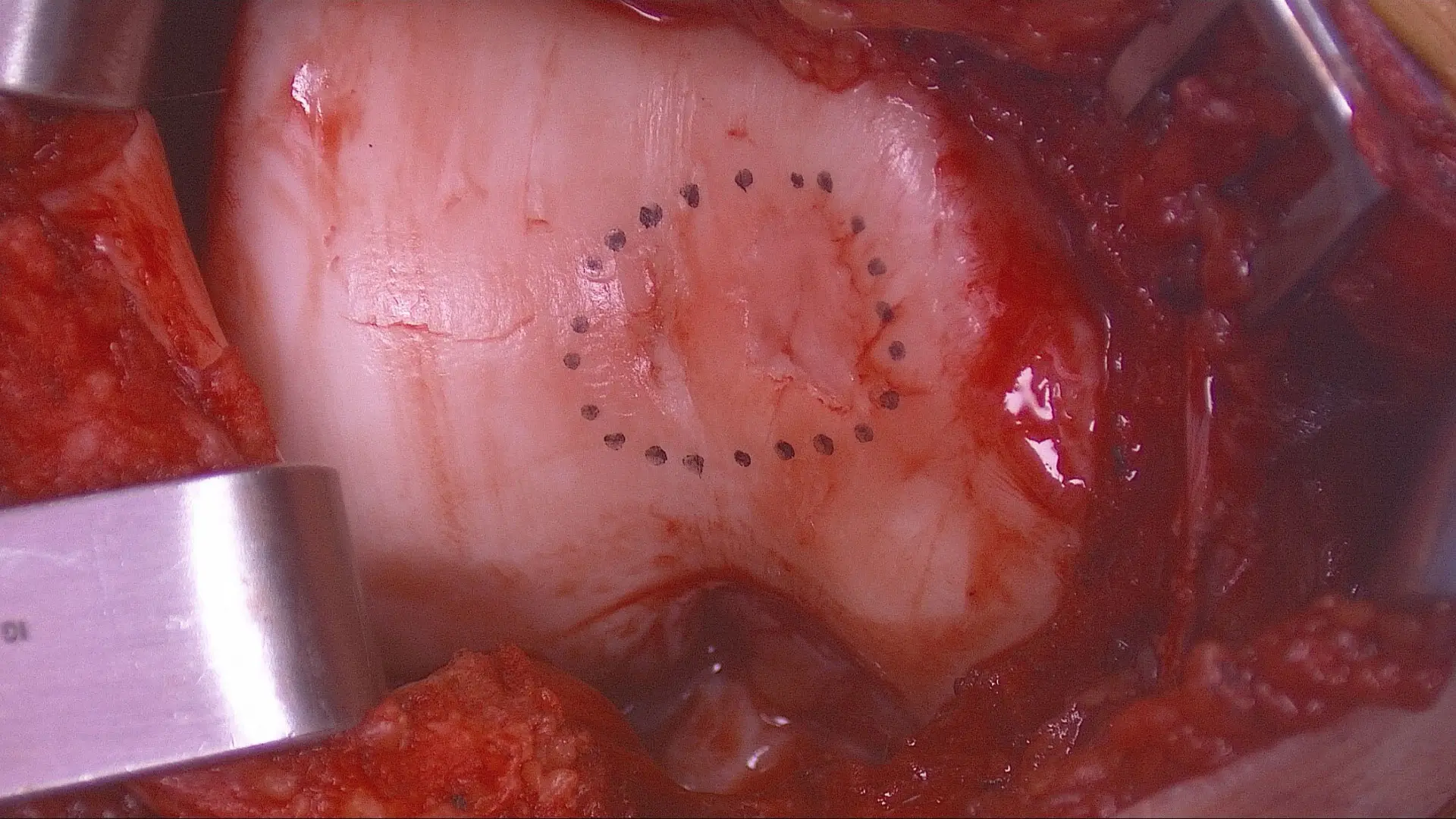

Appearance of torn ACL, good stump appropriate for BEAR procedure.

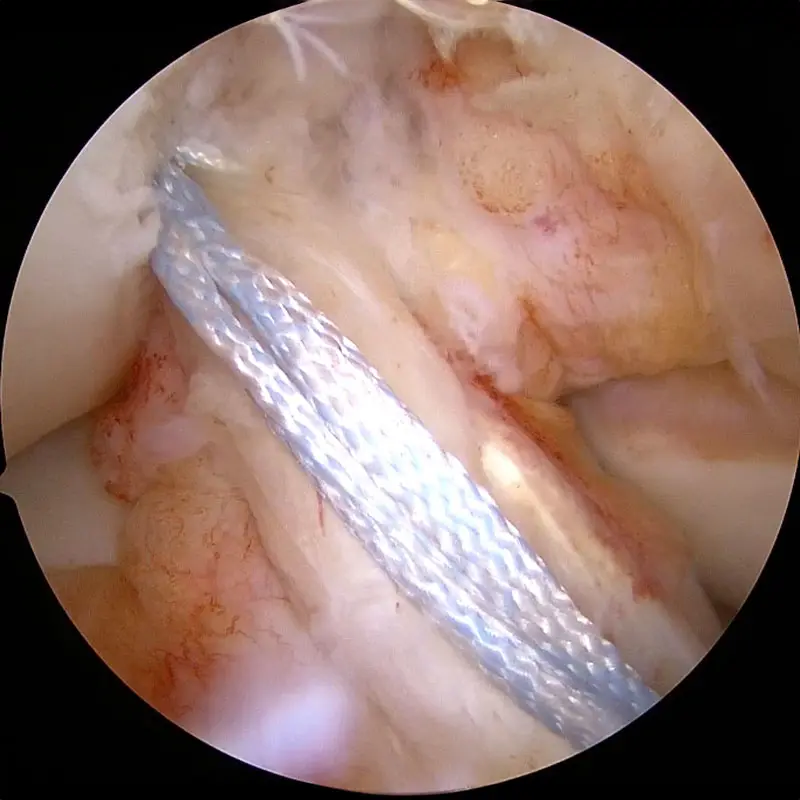

Stitches woven through ACL stump.

Final product with Internal Brace suture tapes in place before insertion of BEAR implant.

View of ACL stump being pulled into position before placement of BEAR implant.

The sports medicine team is conducting ongoing research to follow the progress of ACL healing, in collaboration with Mount Sinai radiologists. Functional tests, such as having patients hop, jump, and pivot, can demonstrate balance and agility, but not whether the ligament is sufficiently mature.

“It’s one thing to repair a ligament, but we still don’t know how to determine when the ligament is strong enough to allow a patient to stress it again with activities such as soccer or basketball. We hope to find a way to do it noninvasively, perhaps with an MRI. Clearly, some people heal faster than others. At what point can they withstand the forces? We need an objective way to determine that,” Dr. Gladstone says.

Cartilage Preservation: MACI and Much More

Unlike ligaments, cartilage has no regenerative potential. Therefore, “what we offer at Mount Sinai in terms of cartilage is a wide variety of techniques, ranging from nonoperative modalities, including orthobiologics, minimally invasive surgical procedures, such as cartilage transplant, or the newer regenerative option, MACI,” Dr. Anthony says.

Injectable orthobiologics, such as platelet-rich plasma and bone marrow concentrate, both of which come from the patient’s own tissue and are injected back into the knee or hip joint, have been shown to decrease pain and improve function, and to provide more durable relief than corticosteroid injections. If these methods fail, surgery is the next step. Here, MACI has been generating excitement since 2016, when it became the first FDA-approved product to apply the process of tissue engineering to grow cells on scaffolds using healthy cartilage tissue from the patient’s own knee.

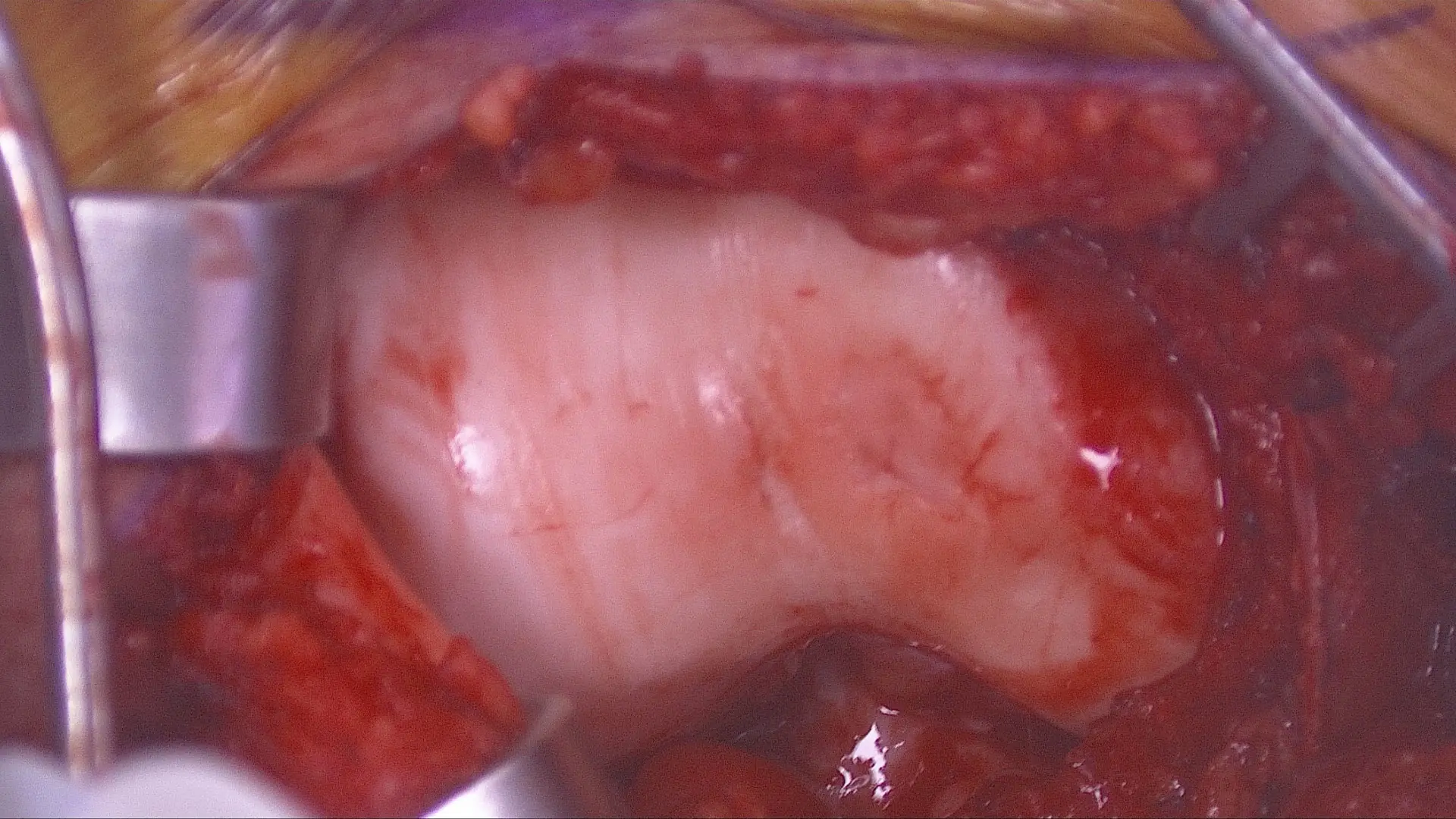

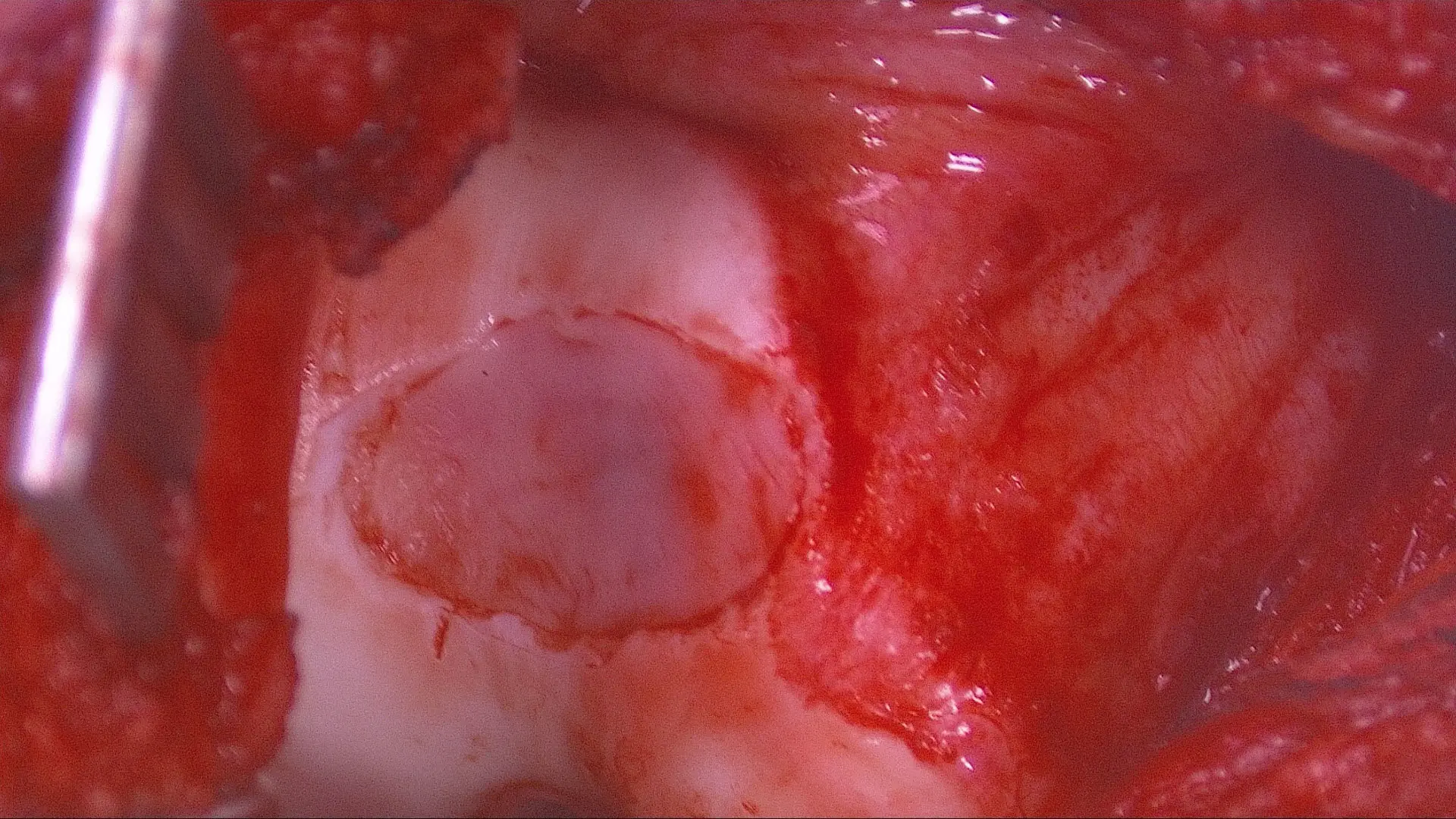

Cartilage damage on the end of the trochlea through which the kneecap (patella) glides when the knee bends and extends.

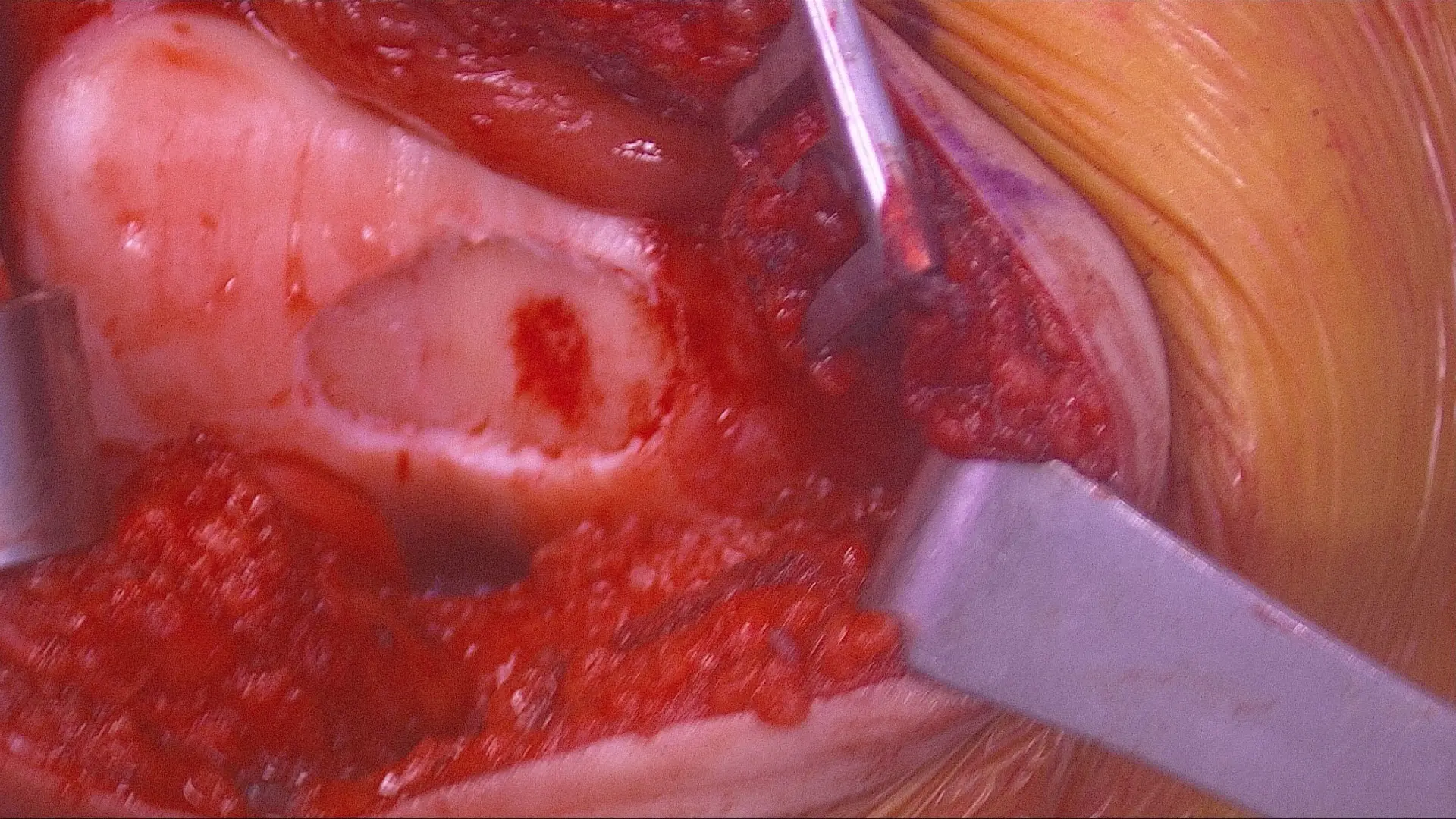

Preparation of the defect by removing all the damaged cartilage down to bone.

Area of cartilage damage marked out.

Cartilage transplant: cultured cartilage cells embedded into a collagen sponge.

Prior to MACI, autologous chondrocyte implantations were typically done by sewing a covering over the damaged area and injecting a suspension of liquid cells underneath the covering and then waiting for them to grow into cartilage. Now, with MACI, “the cells are contained within a boundary. Also, the way the pores are aligned in the collagen is a more columnar pattern that better mimics real cartilage. You’re hopefully jump-starting the process,” Dr. Gladstone explains.

Depending on the size, shape, and location of the cartilage lesion, the team applies other surgical options, such as osteochondral allografts or autografts and marrow stimulation procedures.

“Our group will do whatever is necessary to preserve the joint,” says Dr. Gladstone. “If you want to really take care of patients’ needs fully, particularly athletes’, you have to have the full toolbox available.”

Featured

James Gladstone, MD

Chief of the Sports Medicine Service and Associate Professor of Orthopedics

Shawn Anthony, MD

Associate Chief of Sports Medicine and Assistant Professor of Sports Medicine and Orthopedic Surgery