Nilsson Holguin, PhD, never set out to study a rare genetic disorder linked to osteoporosis. The Mount Sinai researcher, who specializes in the biomechanics and mechanobiology of the spine, was investigating immune cell recruitment in mouse models of intervertebral disc degeneration when he discovered a link between osteoporosis and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), a rare genetic disorder.

AATD is recognized as a disease of the lungs and liver; it is the most common genetic cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Its role in osteoporosis, however, has been largely overlooked. “When we began investigating a mouse model of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, we discovered a variety of spinal changes and realized we could learn much more,” says Dr. Holguin, Assistant Professor, Orthopedics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “This genetic risk for osteoporosis could actually be contributing to patients’ mortality, yet many people don’t even know about it.”

He hopes to change that—and open avenues for new interventions. In 2025, Dr. Holguin received a $200,000, two-year grant from the Alpha-1 Foundation, a nonprofit that aims to find a cure and improve lives for those with the condition. The goal of the study was to explore possible treatments for alpha-1 osteoporosis.

The Musculoskeletal Effects of Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency

Dr. Holguin’s investigations had led him to a gene known as SERPINA1 that was differentially regulated in mice with intervertebral disc degeneration. Diving into the literature, he discovered various mutations in the gene had been tied to AATD. Severe AATD from SERPINA1 mutations is rare. According to the Alpha-1 Foundation, it is most common among people of European ancestry, affecting about 1 in every 1,500 to 3,500 people, though it can occur in people of all backgrounds. He noticed that in addition to lung and liver problems, mice with severe alpha-1 also experienced bone density loss and structural abnormalities in the intervertebral discs. Those changes, he found, seemed to be unique features of AATD and may not be secondary effects of the lung or liver damage.

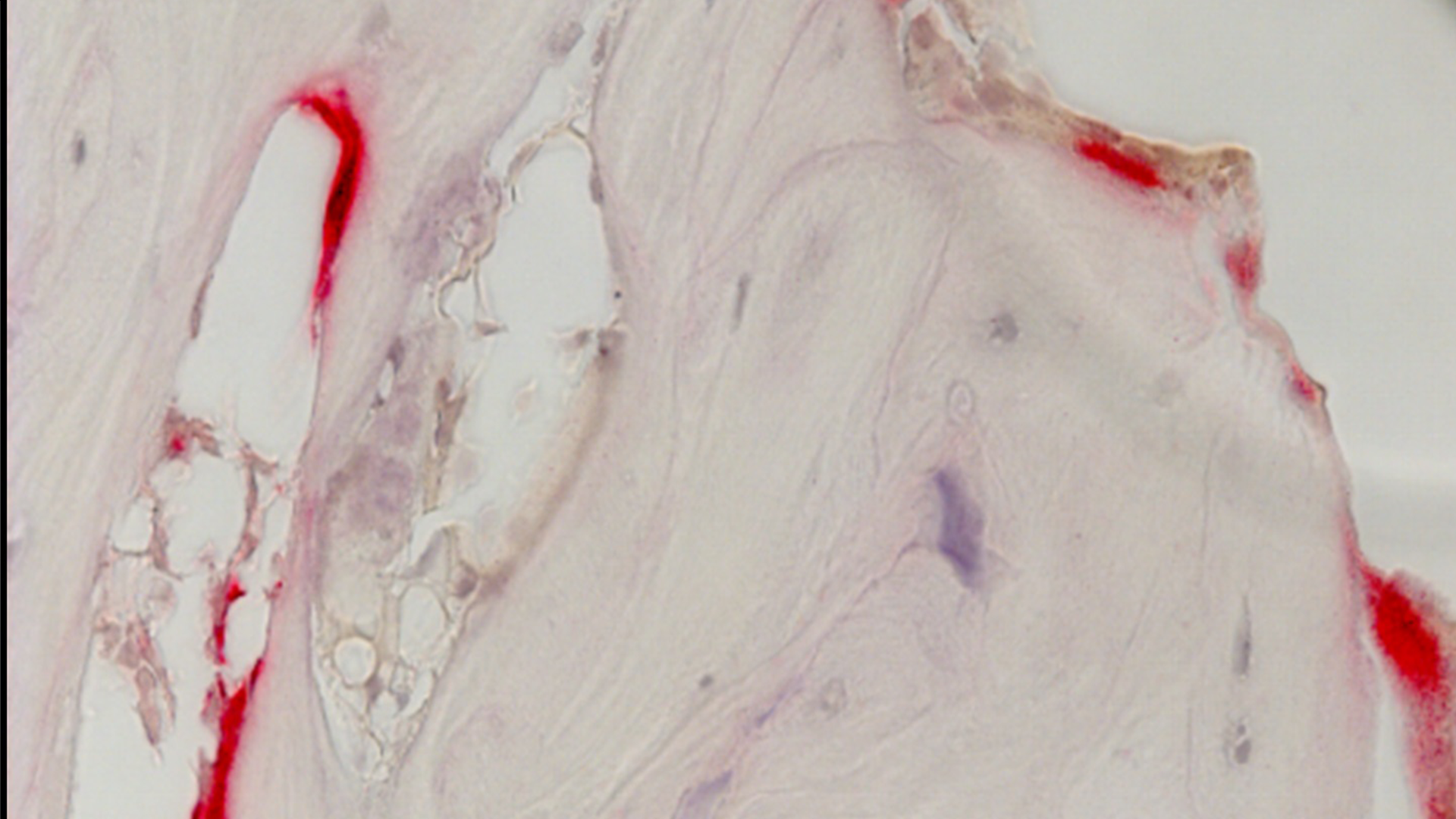

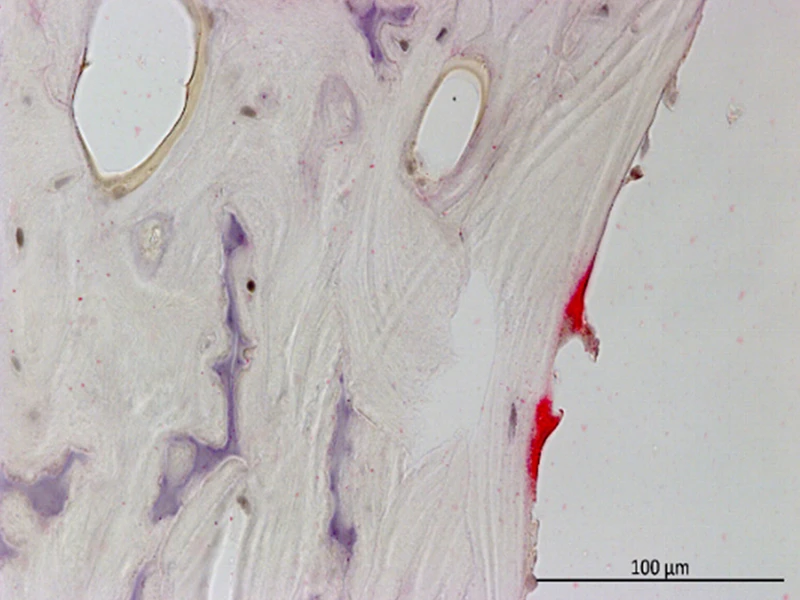

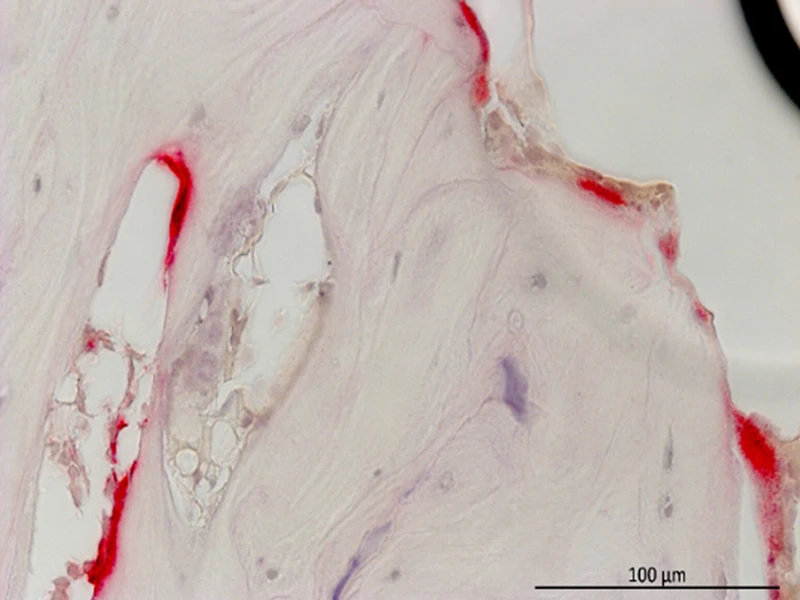

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining for osteoclasts (red) of (left) wildtype and (right) serpinA1ac global knockout lining the trabecular bone. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining for osteoclasts (red) of serpinA1ac global knockout lining the trabecular bone. Scale bar: 100 µm.

Taking a deeper look, Dr. Holguin and his collaborators compared CT images from people with mild, moderate, and severe forms of AATD. They found that even people with more moderate versions—including those who did not have lung disease—may have an elevated risk of osteoporosis. Additionally, up to 5 percent of the general population may be affected by mild AATD, he says. “This risk of musculoskeletal problems could affect a much wider population than we realize,” he adds.

Now, he is hoping to identify possible treatments. People with severe AATD typically receive augmentation therapy, which introduces the missing alpha-1 antitrypsin protein into the body. While augmentation therapy can protect the lungs and liver, Dr. Holguin’s research suggests it does not address musculoskeletal damage. In pilot studies using mouse models of severe AATD, he found neither augmentation therapy nor the bone antiresorptive drug raloxifene worked to normalize bone structure.

With support from the Alpha-1 Foundation, he and his colleagues are studying the combination of augmentation therapy and a more potent bisphosphonate that targets bone resorption, again using a mouse model of AATD. While those mice have the more severe form of AATD, he hopes to extend the research to study potential osteoporosis treatments in people with mild and moderate forms of the disease who may have a hidden risk of low bone density.

Uncovering Clues to Age-Related Intervertebral Disc Degeneration

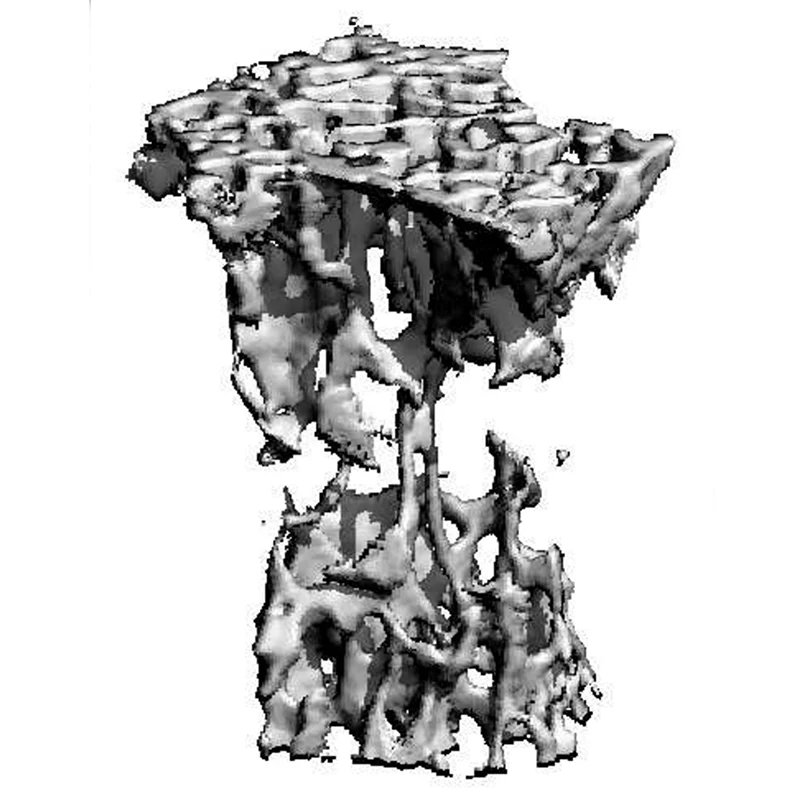

In addition to his grant-funded treatment study, Dr. Holguin is continuing to explore the link between SERPINA1 and musculoskeletal problems. Enabling that work, his lab at the Icahn School of Medicine includes a micro-CT machine, a specialized device that allows him to image the bones of small animals at very high resolution. He and his colleagues have also developed new mouse models with which they can delete SERPINA1 in specific tissues of the body, such as the bones and cartilage, to drill down into the disease process. “By targeting one specific tissue at a time, we can determine whether the changes we see are a direct effect of the gene deletion or if they arise secondarily from other effects of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency,” he says.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of trabecular bone using a high-resolution micro-computed tomography system managed by Dr. Holguin.

Coming full circle to the beginning of this research, Dr. Holguin has found evidence that when SERPINA1 is tamped down or deleted, it promotes the recruitment of immune cells—the process he had originally set out to study when he discovered the osteoporosis-alpha-1 connection. He is following up on those findings in hopes of identifying cytokines or other immune cells that may be contributing to bone loss in mice—and people—with milder forms of the deficiency.

Furthermore, he says, the gene may be involved more broadly in age-related changes to the spine. In older, but not younger, mice with healthy copies of SERPINA1, the gene seems to play a role in recruiting immune cells to injured intervertebral discs.

“Ultimately, this could lead to a new understanding of, and maybe new treatments for, age-related low back pain related to intervertebral disc degeneration,” he says.

Featured

Nilsson Holguin, MD

Assistant Professor of Orthopedics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai