Susan Baum felt trapped by her family’s bleak history with age-related macular degeneration (AMD). “My father was diagnosed with AMD in his 50s, and I watched it slowly rob my younger sister of her independence, just like it had my dad,” she recalls. “I thought I beat the odds … after all, my 50s and 60s went by with no major eye problems, and then I was diagnosed with the condition in 2023, the next step in what seemed like a doomsday scenario for me.”

The doomsday feeling lifted in March 2025 thanks to the introduction of a breakthrough, noninvasive form of light therapy for dry AMD, which she began using in the office of Richard B. Rosen, MD, FARVO, Chief of the Retina Service for the Mount Sinai Health System. Within weeks of Ms. Baum’s first series of light wave treatments, her visual acuity began to improve—well beyond her expectations—and she was eagerly signing up for the next round of therapy in four months.

“Patients have responded well to it,” says Dr. Rosen, referring to the LumiThera Light Delivery System from Valeda, “reporting noticeable improvements in their ability to see details they couldn’t before and generally feeling more confident in how they navigate visually. Those improvements have been modest, but any improvements when it comes to AMD are welcome.”

Dr. Rosen was co-author of a study, LIGHTSITE III, that paved the way for approval of the light delivery system by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in November 2024. New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai (NYEE) was one of 10 clinical centers around the country that participated in the study of 100 patients with early and intermediate dry AMD. After 13 months, 55 percent of treated eyes experienced a significant increase in vision of at least one line of letters on the standard eye chart. Of that group, 20 percent had a gain of two lines and nearly 6 percent had a gain of three lines.

“The study not only showed an improvement in vision, but also in the stabilization of metabolic function, reduction in drusen, and reduced risk for progression to geographic atrophy, which is late-stage AMD affecting central vision,” notes Dr. Rosen, who is also the Vice Chair of Ophthalmic Research at NYEE. His interest in light therapy, also known as photobiomodulation, began in the 1990s with scattered reports of its use in treating dry macular degeneration. The science took a quantum leap years later with the development and approval of the LumiThera system, the first treatment for dry AMD to show improved visual acuity and to slow progression of the disease. AMD afflicts an estimated 20 million people in the United States and there are no approved treatments for dry AMD in its early or intermediate stages beyond antioxidant supplementation, which delays progression in only 20 to 25 percent of eyes.

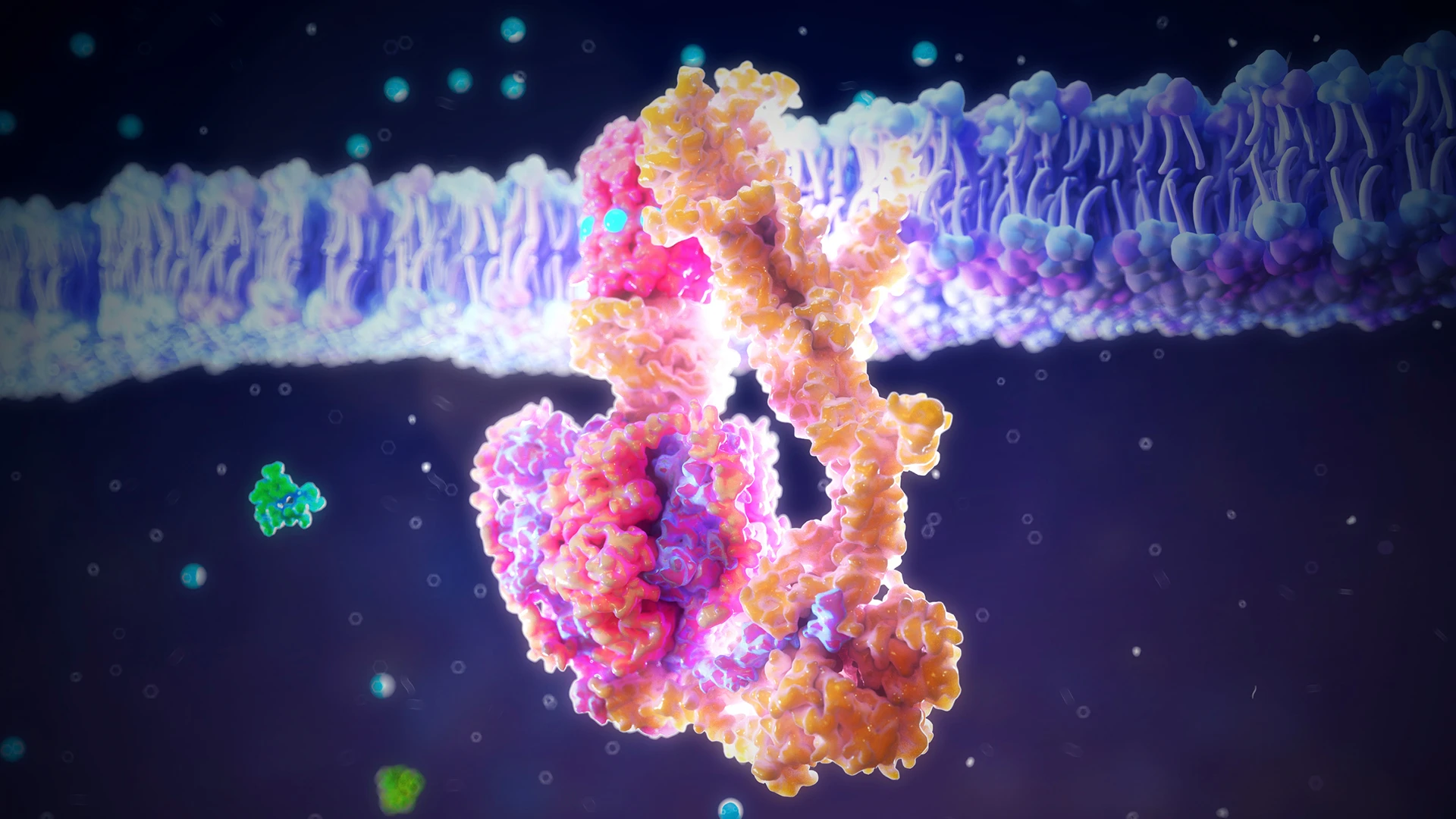

The newly approved light wave therapy involves a series of treatments over three to five weeks with three specific wavelengths (590 nm yellow, 660 nm red, and 850 nm infrared), which act by stimulating improvements in mitochondrial function in retinal cells. This photobiomodulation process occurs when the chain of proteins in the mitochondria responsible for generating adenosine triphosphate (ATP)—the universal energy source of cells—absorbs the wavelengths, enhancing the production of ATP and improving the energy of retinal cells.

Photobiomodulation helps activate the photoacceptors in the mitochondria at a cellular level by stimulating metabolic activity of ATP, preventing inflammation and cell death.

Improvements in cell function via increased enzymatic activity at two separate sites on cytochrome c oxidase (CuA and CuB) help drive the production of the proton gradient required by ATP synthase to produce energy. By restoring the production of energy and signaling molecules, a secondary effect is triggered that sustains improved cell function.

Ms. Baum was among the earliest beneficiaries of this newly approved technology. A voice teacher with a busy practice in New York City, she realized that the job she loved doing for so long was suddenly in jeopardy due to her growing inability to read the notations in sheet music and to see the faces of her students. “Music is my life … and the thought of not being able to follow my passion sent me into a serious depression,” Ms. Baum recalls. She began studying the literature on AMD with the zeal of a research fellow in hopes of finding a treatment and sought out Dr. Rosen with new hope around this new treatment.

She started a course of nine sessions at NYEE, peering into the sleek machine with its programmed sequences of low-intensity light, and quickly started to see results. Back in her studio after the third week of treatment, she looked at the same sheet music from a few days earlier and noticed that the staff lines were less wavy, the G and C chord notations more differentiated. “I almost couldn’t believe it,” she exults. “Even going down subway stairs to catch a train, I noticed that the lip of the steps was more clearly defined, reducing the chance of a dreaded fall.”

At a follow-up visit in May, Ms. Baum reported the encouraging news to Dr. Rosen; it was consistent with comments he was hearing from other patients using the device. Meanwhile, Dr. Rosen, who has been at the forefront of studying mitochondrial dysfunction in retinal disease for the past 13 years, is involved in other studies investigating the application of light therapy to retinal disorders that include diabetic retinopathy, central serous chorioretinopathy, and glaucoma. A recent grant from the Leon Lowenstein Foundation will further allow his lab to study the oxidative stress on the mitochondria in patients both before and after LumiThera treatment.

For now, though, anecdotal evidence from highly motivated patients like Ms. Baum are as meaningful to Dr. Rosen as the findings of any multi-site, placebo-controlled trial. “You’ve given me hope,” she wrote to her ophthalmologist in April, “that I might retain my vision and maybe even improve it, despite facing a hereditary and seemingly inevitable loss.”