Julia Fallon, MD, a retina fellow at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai (NYEE), likes to think of each surgery as a work of art, combining elements from her extensive surgical training in unique ways to meet the needs of each patient.

That mindset served her particularly well when she recently teamed up with volunteer faculty instructor Alexander Barash, MD, to perform surgery for the dislocated lenses in both eyes of a patient with Marfan syndrome (MFS), a serious complicating factor.

“We had to treat his eyes differently than most secondary lens cases because his anatomy was so different,” Dr. Fallon explains. “We had to really think the case through and make important changes, like how far back in the eye to position the lens, as the surgery progressed. In addition, the removal of the displaced lens and surrounding vitreous gel had to be performed with extreme care due to the high risk of retinal detachment in patients with this connective tissue disorder.”

Perhaps the boldest stroke by these two highly skilled ophthalmologists was the decision to use a procedure known as the Yamane technique for scleral fixation of intraocular lenses. This surgical procedure was the perfect remedy for a patient whose lens implant could not be supported by the capsular bag, which had completely separated from its attachment to the wall of the eye as a result of the patient’s underlying condition. This technique, brought to NYEE about six years ago by Dr. Barash, indeed proved a masterstroke for the patient, Dean Klingler. Weeks after the completion of the second procedure on his left eye, he described the “miracle” of seeing for the first time road signs and other distant objects without the need for very thick glasses.

The ordeal began for Mr. Klingler, 57, on a Sunday morning in January 2023 when he woke up with blurry vision in his right eye. “It continued to get worse during the day,” he recalls, “and I finally walked over to the eye clinic at New York Eye and Ear, just four blocks from my apartment. Through providence or good luck, I wound up going to the best place in the field.”

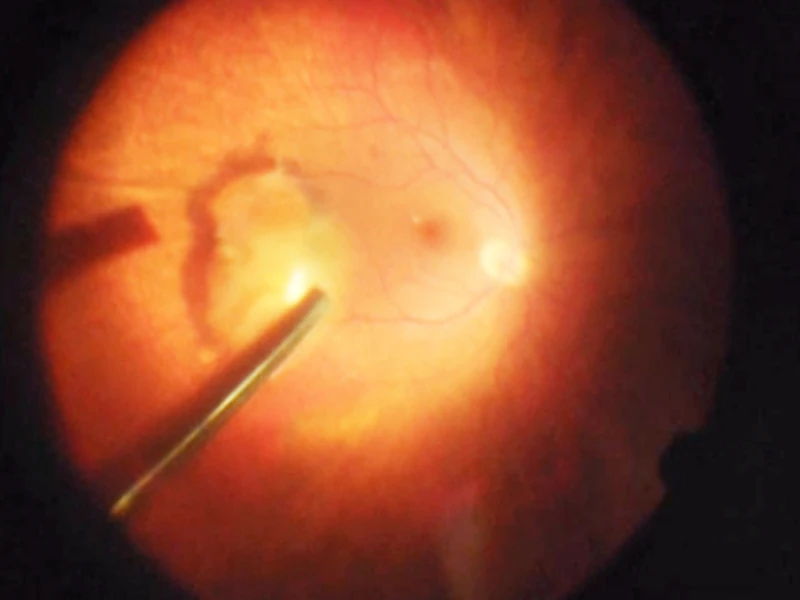

Residents staffing the clinic found that the dislocated lens was blocking Mr. Klingler’s pupil, preventing aqueous fluid circulation and drainage from the eye, which caused his intraocular pressure to be 60 mm/Hg, three times the normal amount and risking blindness if not urgently addressed. This was particularly troublesome when coupled with his MFS, a genetic condition that produces aberrant elastic fibers throughout the body, including in the aorta and the zonules—the suspensory ligaments attaching the lens within the eye, which become stretched out, and over time can rupture, leading to lens dislocation.

Dr. Barash, who saw the patient during his repeat visits to the downtown clinic, sought to bring the pressure down with eye drops and oral medications. “Given the patient’s history of major heart surgery, we wanted to make sure he had appropriate clearance from his cardiologist before retinal surgery to ensure his safety,” says Dr. Barash, who maintains a private practice in Manhattan in addition to his volunteer work training residents and fellows at the Bendheim Family Retina Center at NYEE, as well as Elmhurst Hospital Center in Queens, a Mount Sinai affiliate.

Alexander Barash, MD

Julia Fallon, MD

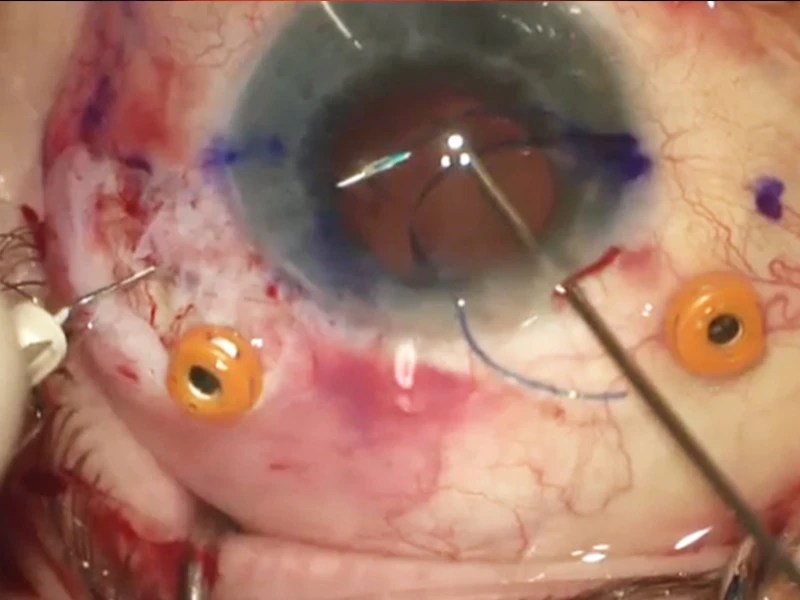

For the first of the two surgeries on January 24, Dr. Barash asked Dr. Fallon, who was on duty that day, to assist. It was a fortuitous pairing since both had performed the Yamane technique many times, often together. The dislocated lens was removed with vitrectomy but there was no zonular support for a new intraocular lens. The Yamane technique was the ideal option to fixate the new lens, as the sclera was thin in this long MFS eye, and suture-based fixation can erode through the sclera with time and cause the new lens to fall out of position. Similarly, the iris can also be thinned in patients with MFS and the lens would be similarly unstable affixed to the iris.

The Yamane technique, which requires considerable training, involves using a tiny corneal incision to insert the new lens. In order to affix the lens to the sclera to ensure its long-term stability, two 30-gauge needles housing the lens haptics were inserted through the sclera, creating a tunnel in which the haptic arms could rest. When the surgeons withdrew the needles, the haptics remained and became anchored in those scleral tunnels. The surgeons then cauterized the protruding ends of each haptic to fashion flanges that prevented the arms from slipping back into the eye.

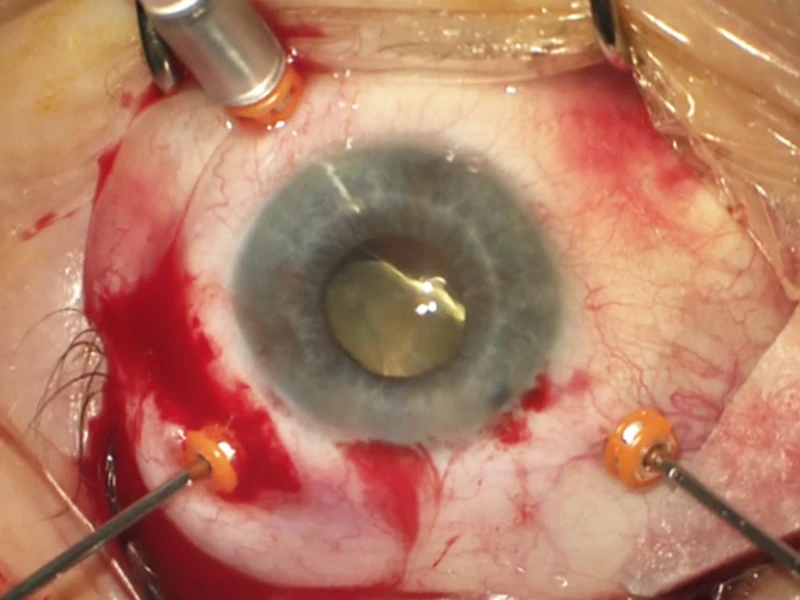

Lens dislocation in the left eye.

Scleral fixation of intraocular lenses using the Yamane technique.

Lens sitting on the retina after falling to the back of the eye due to weak support structures (zonules), creating a blockage that prevented aqueous fluid circulation and drainage from the eye.

While the surgery was a success, it was in a sense a tune-up for the analogous second operation six months later on the left eye.

“I learn a little bit from each case, but probably more from this one because of the uniqueness of his anatomy,” acknowledges Dr. Fallon.

The abnormal size and shape of Mr. Klingler’s eyes due to the MFS meant that the normal anatomical structures were stretched and acted differently. That awareness served her and Dr. Barash well on the follow-up surgery when they revised critical aspects of the procedure, such as moving the intraocular lens back a half-millimeter from the 2.5 mm of the first. “We made a lot of adjustments,” confirms Dr. Barash, “because of the configuration of the eye where everything was floppy and worked differently.”

To the surgeons’ satisfaction, the second procedure was even smoother than the first. Validation came from the patient himself, whose intraocular pressure returned to normal in the following weeks, while his vision without glasses or contacts improved substantially to 20/30.

“I can’t believe how perfect my vision is now,” exclaims Mr. Klingler, a fund-raiser for a nonprofit environmental organization. “There were certainly more than a few sleepless nights when I was wondering whether I would ever see well again. You could say I was lucky enough to find doctors at the top of their game.”

Mr. Klingler in his East Village apartment.