Recent surgery to repair an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) in the orbit compressing the optic nerve of a five-year-old boy showed the benefits of combining the specialized skills and technical resources of New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai (NYEE) and the Mount Sinai Health System.

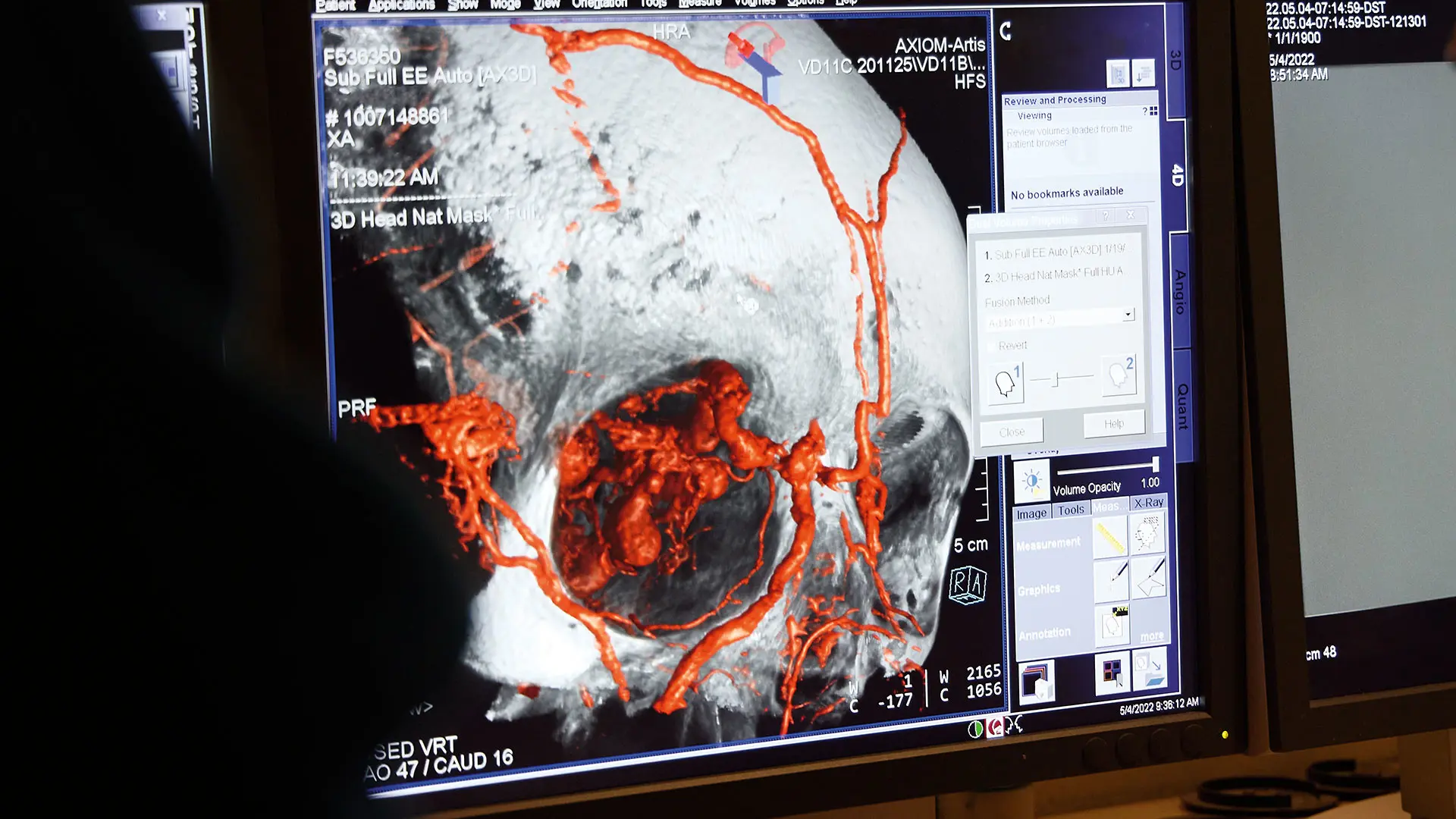

In the four-hour procedure at The Mount Sinai Hospital, an NYEE oculoplastic surgeon provided difficult intravascular AVM access for the neuro-endovascular team at Mount Sinai, with the help of a sophisticated 3D fluoroscopy-guided angiography system and ultrasonography.

“These cases are so complex that you really need a multidisciplinary team to reach the malformation and effectively treat it,” says Valerie I. Elmalem, MD, Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and a neuro-ophthalmologist and oculoplastic surgeon at NYEE, who teamed up with Johanna Fifi, MD, Associate Director of the Cerebrovascular Center at Icahn Mount Sinai, on the procedure. The patient is doing well postoperatively despite a host of challenges that pushed the surgeons to their limits, which underscores the synergies possible through joining the skill sets of two acclaimed medical centers.

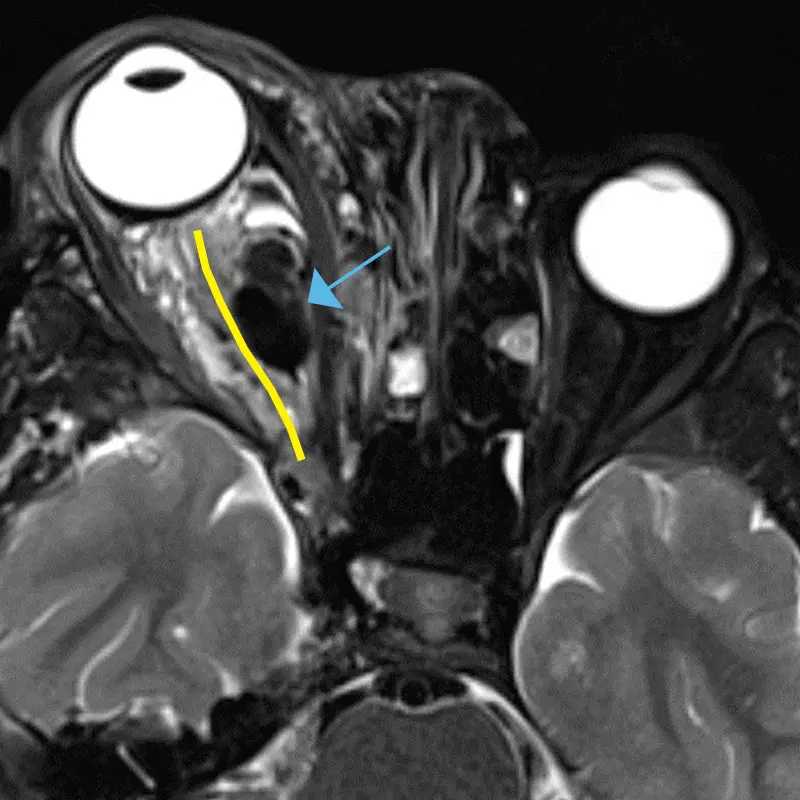

The young patient, Bryson Hadden, faced a welter of issues. From birth, he developed AVMs and venolymphatic malformations in various regions of the head. When his right eye began bulging in August 2021—a condition his mother, Brittny Hadden, recalls as “really nasty-looking and painful”—an MRI and magnetic resonance angiography revealed an intra-orbital arteriovenous as well as multiple intracranial arteriovenous malformations. This tangle of blood vessels, also known as a fistula, forms abnormal connections between arteries and veins, and the resultant expansion of the previously small, low-flow veins compresses the surrounding tissues. It also runs the risk of rupturing and causing massive bleeding.

3D reconstruction with angiogram showing the AVM superimposed on skull/orbital bones to identify surgical anatomic relationships

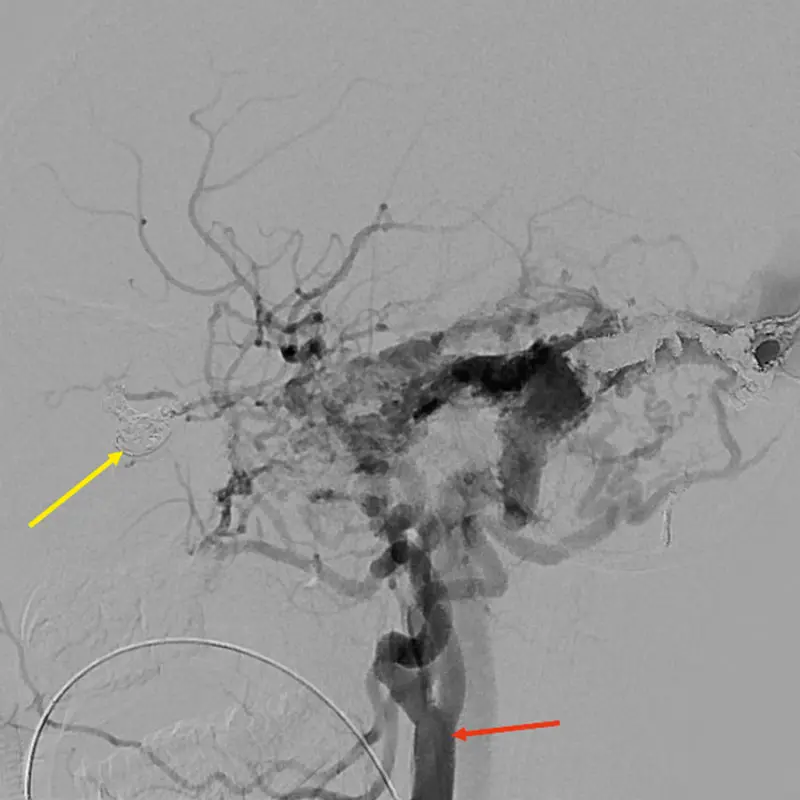

A referral from Bryson’s ophthalmologist to Mount Sinai set in motion a series of surgical interventions. In January, Dr. Fifi treated an intracerebral malformation, detecting at the time the new orbital malformation that was compromising the patient’s eyesight. But she also realized that intra-arterial access to the AVM—needed to perform standard coil embolization—would require an extra set of specialized hands.

“Normally, when we treat these kinds of malformations, we go through the jugular to get access to the vein, but in this patient’s case, that route was occluded, so we had to directly puncture the vessel by the orbit,” explains Dr. Fifi, who had joined forces with Dr. Elmalem on a previous surgery. “That’s when I asked Dr. Elmalem to get involved. As an oculoplastic surgeon, she has the ability to get direct surgical access to the veins in the orbit.”

It proved to be anything but routine surgery, however. “All of us were very nervous about this case because of all the important blood vessels that were connecting to the ophthalmic artery,” says Dr. Elmalem. “If a clot were to form and travel through the artery, the patient would go blind.” Another challenge was the patient’s age—a rambunctious five-year-old who is also on the autism spectrum. The usual access to the vein through the orbit could have led to difficult-to-manage vision-threatening postoperative bleeding from the child rubbing his face or eyes.

3D reconstruction of an angiogram of the right common carotid artery showing large orbital AVM (circled)

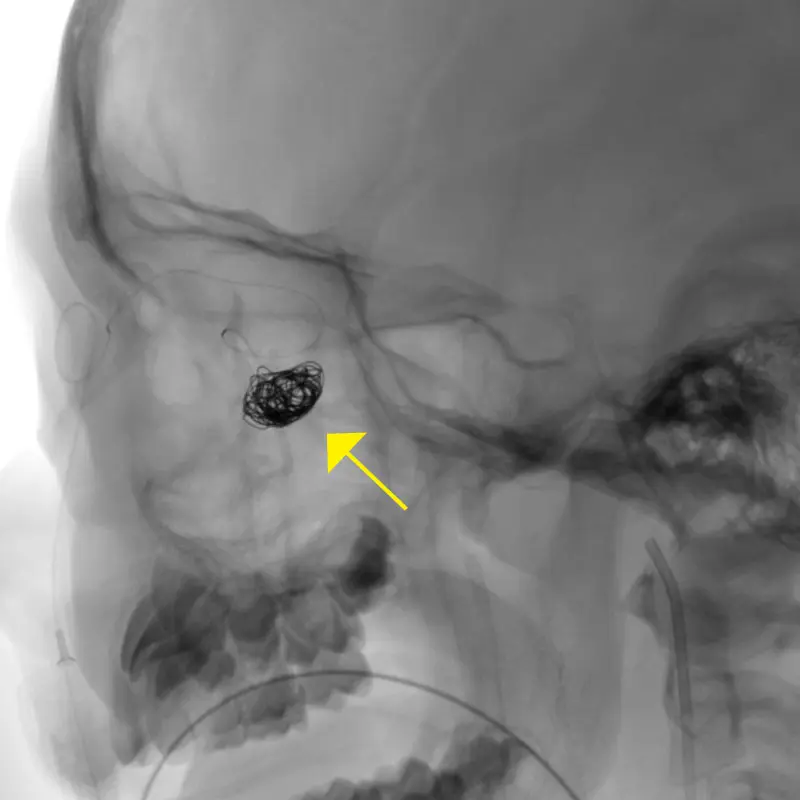

Platinum coil being inserted into the AV fistula (yellow arrow)

Axial MRI showing optic nerve course (yellow line) with compression by AVM (blue arrow)

Post-treatment angiogram showing closure of the AV fistula. Yellow arrow: Platinum coil material inside the AV fistula blocking the flow of blood between the artery and vein; red arrow: Right common carotid artery

Dr. Elmalem’s solution was to avoid any incision by gaining access from the face, through one of the dilated vessels that ran medial to the orbit. While the strategy was sound, its execution proved onerous. Every effort to advance a microcatheter through a facial puncture into the vein to allow treatment of the fistula through coil embolization was met with resistance. “We kept trying different areas of the face, and after an hour and a half were finally successful by going through the angular vein that runs between the side of the nose and inner corner of the eyelid,” explains Dr. Elmalem. That cleared the way for Dr. Fifi and her team to close off the faulty connection between vein and artery with a metallic occluding coil.

Integral to the delicate surgery was a sophisticated neuronavigational system at Mount Sinai that NYEE was able to tap into. Specifically, the hospital’s fluoroscopy-guided angiography allowed both teams of surgeons to pinpoint the precise location of the fistula—where the artery connects to the venous pouch—going well beyond just the bony structure normally seen by Dr. Elmalem in her orbital surgery. Throughout the procedure, this technology provided vital 3D guidance to surgeons—including viewing the coils entering the fistula—from their monitors.

Postsurgically, Bryson has continued to make progress. Closing the fistula in the right eye produced a change in his vision from 20/200 to 20/80, with further improvements expected as the left eye is patched for increasingly longer periods to treat his amblyopia.

“Bryson is always happy, and his problems haven’t held him back in school,” says his mom. While the family’s three-hour trips from their home in upstate New York to Manhattan for treatment are demanding, she calls them “well worth the time given the high-quality care Bryson is receiving” from the doctors at Mount Sinai and NYEE.

Bryson with his mom and dad at Stuyvesant Square Park following his third postop visit with Dr. Elmalem in July 2022

Featured

Valerie I. Elmalem, MD

Associate Professor of Ophthalmology

Johanna T. Fifi, MD

Associate Professor of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and DIagnostic, Molecular and Interventional Radiology