Preeclampsia was historically seen as clinically benign, a condition that resolved upon delivery without serious health consequences for the mother. While more recent evidence has undermined that premise—unearthing a critical link between elevated blood pressure during pregnancy and hypertensive disorder—a 2024 Mount Sinai study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Advances shows for the first time the potential severity of its long-term effect on the mother’s risk of cardiovascular disease.

“Our findings suggest that the longer the mother’s exposure to elevated blood pressure, the greater the risk of cardiovascular complications for the mother, and even for her child and grandchild,” says lead author Leslee Shaw, PhD, Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science, and Medicine (Cardiology) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “For a woman experiencing early or severe preeclampsia, that risk starts to accelerate within a couple of years following delivery, and remains elevated 15 to 20 years later. That’s why it’s so vital for women and their doctors to focus on blood pressure control and management during pregnancy–something our field has not done a very good job of in the past.” The study was led by Dr. Shaw and other renowned specialists, including Joanne L. Stone, MD, MS, Ellen and Howard C. Katz Chair and Professor in Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science; and Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, MBA, Director of Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, and the Dr. Valentin Fuster Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

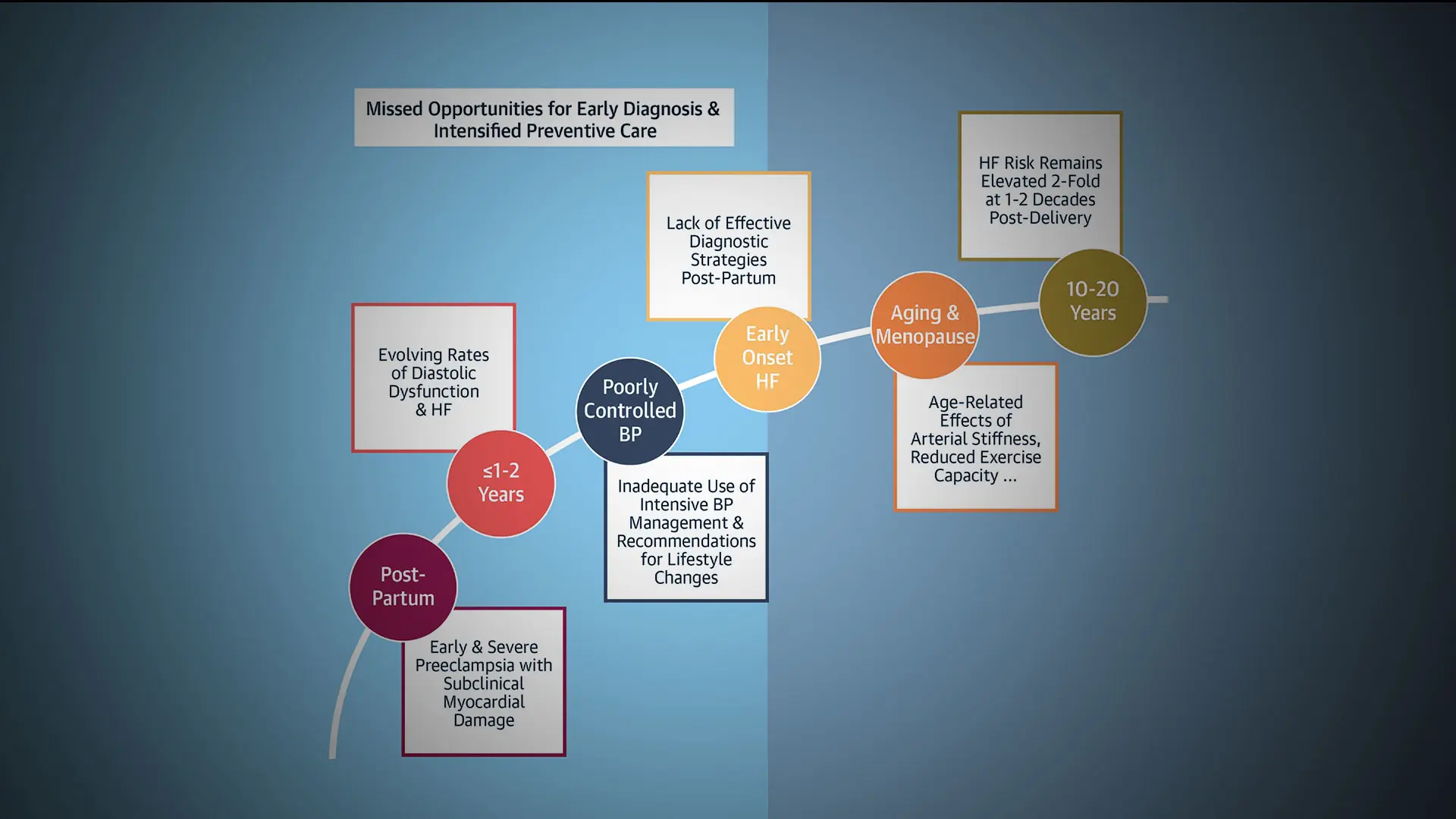

Preeclampsia, defined as systolic BP ≥40 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg after 20 weeks of gestation (and up to six weeks postpartum), occurs in 5 to 8 percent of all pregnancies. The Mount Sinai study carefully differentiated between early and late preeclampsia. Early preeclampsia, referring to less than 34 weeks of gestation, exhibits a pattern of hyperinflammation and abnormal angiogenesis, which can contribute to early-onset heart failure. That risk remains elevated decades later and can lead to premature death. Late preeclampsia occurs upon delivery or more than 34 weeks of gestation, and is more common, with a benign perinatal course.

“Early preeclampsia is decidedly higher risk for maternal and fetal adverse outcomes, including fetal growth restriction,” says Dr. Shaw, who is Director of the Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute and is widely known for her research on cardiovascular disease in women. “And among the many maternal characteristics, age 35 and above is strongly linked to preeclampsia. Black women are also at much higher risk of preeclampsia and heart failure, though we don’t completely understand the pathophysiology of that.”

Graphical abstract of the study.

“Our findings suggest that the longer the mother’s exposure to elevated blood pressure, the greater the risk of cardiovascular complications for the mother, and even for her child and grandchild.”

Leslee Shaw, PhD

More widely known is the role of autoimmune disease such as type 1 diabetes and the inflammatory effects of obesity in promoting early preeclampsia. In fact, research suggests that these cardiometabolic conditions are intertwined with blood pressure, forcing the heart to work harder to push blood through more rigid vessels. The fact that roughly 40 percent of the U.S. population is obese, with women showing slightly higher rates than men, has served to exacerbate preeclampsia in recent decades.

Against this challenging background, the Mount Sinai team urged adoption of a clinically sound and aggressive set of practice guidelines for women with early or more severe preeclampsia designed to foster early detection, and prevention, of heart failure. That process needs to begin with a baseline echocardiogram at the time of diagnosis, with women who show persistently elevated BP receiving serial echocardiographic evaluations starting at one year after birth, the study says. That postpartum monitoring should be coupled with regular follow-up care to control hypertension, including pharmacologic intervention and lifestyle modifications, such as regular exercise and low salt intake. Patient education akin to cardiac rehabilitation that is focused on diet, physical activity, and medication adherence will provide lifelong benefits, the study concluded.

“Women at risk of cardiovascular disease from preeclampsia should be referred to a cardiologist or hypertension specialist soon after delivery, with an earlier consultation also recommended,” Dr. Shaw says. “We’re now learning that these patients don’t have to endure a lifetime of heart failure and premature death. If they work closely with their doctors and empower themselves to maintain normal blood pressure and adopt healthful lifestyle choices, they can be assured of a much different long-term risk profile.”

Featured

Leslee Shaw, PhD

Director of the Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute

Joanne L. Stone, MD, MS

Chair and Professor of the Raquel and Jaime Gilinski Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science

Deepak L. Bhatt, MD, MPH, MBA

Director of the Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, and the Dr. Valentin Fuster Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine