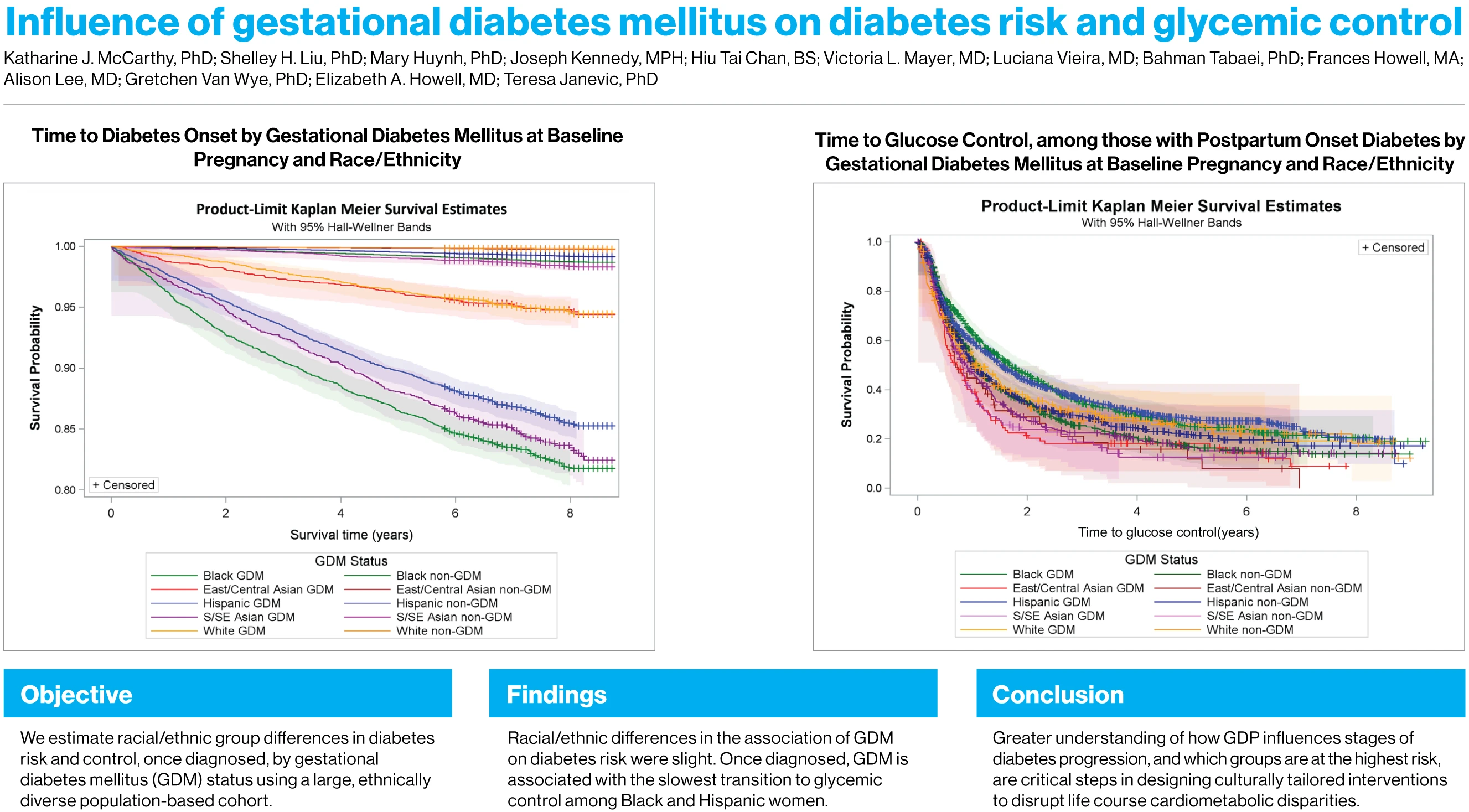

People who develop diabetes following pregnancy were significantly less likely to be able to bring it under control if they had experienced gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) during their pregnancy, especially if they were Black or Hispanic, Mount Sinai researchers found. The results were published in June 2023 in the journal Diabetes Care.

The study found that people who experienced gestational diabetes were more than 11 times as likely as those whose pregnancies did not involve gestational diabetes to develop diabetes within nine years after delivery. The researchers found that in the first 12 weeks to one year postpartum, there was the highest incidence of diabetes and the least likelihood of diabetes control. The researchers said these findings suggest that regular diabetes screenings, particularly in the early postpartum period, have the potential to alter the speed and course of disease progression in the years to come.

Gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes are among the leading risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Both conditions are also marked by persistent racial and ethnic disparities, often a result of gaps in access to health care and treatment. While existing research has focused on how gestational diabetes influences type 2 diabetes later in life, few have examined how gestational diabetes influences disease severity or control after diabetes diagnosis.

“Our findings highlight the importance of regular diabetes screening following gestational diabetes, particularly in the first 12 months following delivery, in order to facilitate early detection and appropriate diabetes management,” says corresponding author Katharine McCarthy, PhD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science, and Population Health Science and Policy, and a member of the Blavatnik Family Women’s Health Research Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

“Our findings highlight the importance of regular diabetes screening following a gestational diabetes, particularly in the first 12 months following delivery, in order to facilitate early detection and appropriate diabetes management.”

- Katharine McCarthy, PhD, MPH

In this study, which was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, researchers explored how race, ethnicity, and gestational diabetes interact to influence both diabetes risk and glycemic control, or achieving clinical recommendations for blood sugar levels. Researchers found that the cumulative incidence of diabetes was 11.8 percent for people who experienced GDM and 0.6 percent among people without GDM.

The researchers found that the groups with the highest incidence of gestational diabetes were people of South and Southeast Asian descent; these groups had a somewhat lower risk for diabetes after delivery, compared to other racial/ethnic groups, although the risk was still high. Among those who experienced diabetes after delivery, the researchers found a history of gestational diabetes was associated with more difficulty in controlling glucose levels. In particular, of those with postpartum-onset diabetes following gestational diabetes, Black and Hispanic people experienced a longer time to achieve control of their glucose levels than those without gestational diabetes.

For the study, the research team developed a novel population-based cohort of more than 330,000 postpartum women in New York City, using linked birth and A1c Registry data from 2009 to 2017. The records included data about pregnancy-related comorbidities, including gestational diabetes and gestational hypertensive disorders; self-reported race and ethnicity; and sociodemographic characteristics including age, nativity, education, and insurance type or status. About 2,800 women with pre-pregnancy diabetes were excluded from the cohort.

Incident diabetes was defined as the second date of an A1c test with a value of 6.5 percent or more. Glucose control was defined as an A1c value of less than 7 percent after postpartum diabetes diagnosis. To distinguish between GDM and diabetes onset, study observation began at 12 weeks postpartum for all analyses. Adjustment for screening bias and loss to follow-up modestly lowered racial/ethnic differences in diabetes risk but had little influence on glycemic control.

Through their analysis, the Mount Sinai researchers were able to confirm prior estimates of diabetes risk attributed to gestational diabetes and build on limited existing evidence of racial and ethnic differences in the influence of gestational diabetes. The data supports policies that both facilitate and expand access to health care after delivery, such as extending postpartum coverage under Medicaid.

“Understanding racial/ethnic differences in the influence of GDM on diabetes progression is critical to disrupt life-course cardiometabolic disparities,” the study concluded.

Featured

Katharine McCarthy, PhD, MPH

Assistant Professor of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Science, and Population Health Science and Policy