Researchers found that presence or history of fever, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) white blood count (WBC) ≥50 cells/microliter (µL), and CSF protein ≥75 mg/deciliter (dL) are significantly helpful in ruling out an autoimmune etiology.

It is the largest study of its kind in the number of cases and biomarkers assessed.

The research is unique in that it assessed 333 cases of confirmed acute meningoencephalitis, making it the largest study of its kind to date, and a wider range of biomarkers for both infectious and autoimmune etiologies—the two main causes of encephalitis. The study was published in 2022 in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology. Anusha K. Yeshokumar, MD, Assistant Clinical Professor of Neurology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, was the senior author.

"What we found was that if a patient presents with fever, has a relatively high number of white cells in their spinal fluid, and has a relatively high level of protein, it is useful in determining that the etiology is likely infectious even if no clear pathogen has been identified,” says principal investigator Jessica Robinson-Papp, MD, MS, Professor of Neurology, Icahn Mount Sinai. “It means that we can initiate and continue to administer antimicrobial therapies with a considerable degree of confidence.”

The team focused on data that could be collected within 48 hours of hospitalization.

Mount Sinai was one of three New York City tertiary care hospitals participating in the retrospective study, which examined patient data collected by the New York City Encephalitis Consortium, a cooperative of neurologists dedicated to studying encephalitis. Researchers focused on data that could be collected within the first 48 hours of patient hospitalization, including clinical signs such as fever, simple CSF studies (such as WBC, glucose, protein, and oligoclonal bands), widely available blood tests (such as WBC, ESR, and CRP), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and electroencephalographic (EEG) results.

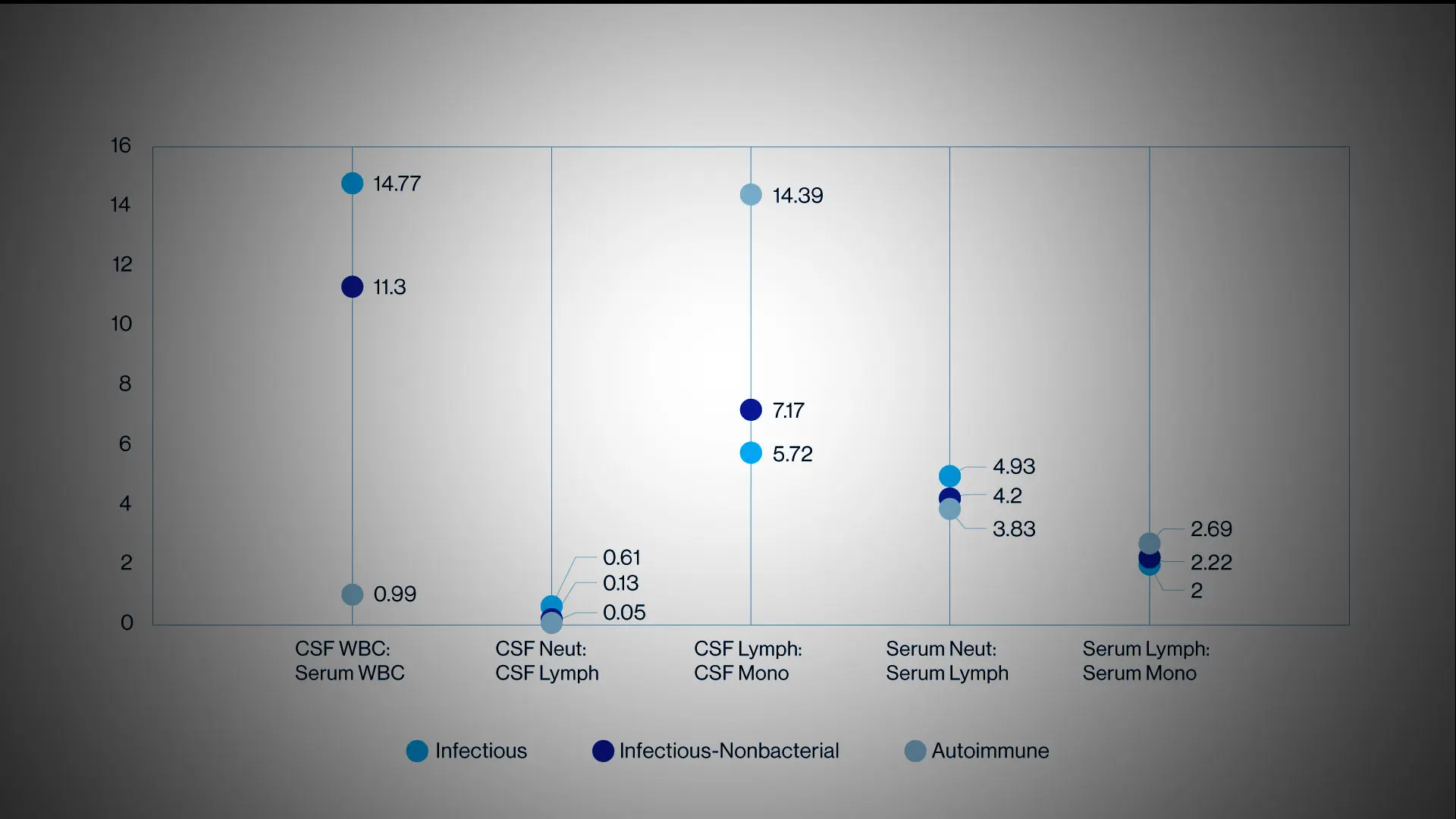

Using these variables, researchers also explored the differences between the infectious- nonbacterial subgroup (typically viral etiology) and the autoimmune cohort. Although the CSF profile of patients with bacterial and infectious-nonbacterial encephalitis are starkly different, both infectious-nonbacterial and autoimmune encephalitis (AE) can have mild elevations in CSF WBC and protein. The research team found that most patients diagnosed with AE presented without evidence of fever, had more normal CSF WBC and protein, and normal serum ESR and CRP—and that EEG was not helpful in distinguishing the two groups.

The researchers also noted that patients with an AE etiology had a higher median serum WBC than the infectious-nonbacterial cohort, although it did not meet the threshold to be considered abnormally elevated. However, they did not observe this trend when comparing the entire infectious encephalitis (IE) cohort against the AE cohort. “We hypothesize that the lower WBC in the blood of infectious-nonbacterial encephalitis patients could be because most of these patients had viral infections that can temporarily impair the ability of bone marrow to produce WBCs,” Dr. Robinson-Papp explains.

Findings provide some criteria that can be beneficial in determining …

… whether a patient is presenting with an autoimmune or infectious etiology.

“This is a very preliminary study and thus we are not recommending that the findings be applied across the board, but they do provide some criteria that can be beneficial in determining whether a patient is presenting with an autoimmune or infectious etiology,” says Allison P. Navis, MD, who was among the researchers who helped collect the data for Mount Sinai. Dr. Navis is Assistant Professor of Neurology in the Division of Neuroinfectious Disease.

Further studies are required to affirm the validity of these findings. There are plans for a prospective study that could result in a standardized protocol for assessing patients, and there is the potential to conduct an interventional study to assess how patients respond to earlier initiation of treatment for an autoimmune etiology. “I think it would also be interesting to explore the possible long-term outcomes among these patients, such as their risk for developing cognitive issues,” Dr. Robinson-Papp says. “By identifying those risks, it could enable earlier interventions or the development of new therapies, all of which could be beneficial for patients.”

Adds Dr. Navis: “In the meantime, perhaps our findings will provide clinicians with the reassurance that they can be more aggressive in early interventions.”

Cover image credit: Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology