Nathalie Jetté, MD, MSc

In the following Q&A, Dr. Jetté discusses her work on increasing access to care for two vulnerable populations: older adults with epilepsy and patients with drug-resistant epilepsy for whom surgery might be the most appropriate treatment.

Q. Why do older patients pose a unique challenge for neurologists and

other physicians who diagnose and treat epilepsy?

Dr. Jetté: The broad answer is they are often more complex cases. More specifically, older adults—the age threshold being 65 to 70—often have comorbidities such as dementia, stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, or other central nervous system conditions that not only greatly increase their risk of epilepsy, but may mask and make it more difficult to diagnose the disease. A national study among veterans showed that stroke and dementia nearly doubled the odds of hospital admission in older people with new onset epilepsy. In very young patients, by comparison, genetic and neurodevelopmental disorders are more prominently associated with epilepsy.

Epilepsy is the third most common neurological disorder in people 65 and older.

– Nathalie Jetté, MD, MSc

Q. What have your studies revealed about the magnitude of the epilepsy problem in older individuals?

Dr. Jetté: We’ve learned that while epilepsy is a common condition in the older population, it has received comparatively little attention from the clinical and research communities. This needs to change. Epilepsy is the third most common neurological disorder in people over 65, and this age bracket is the fastest growing of all age groups worldwide. We also know from our work that older people with epilepsy have more falls and fractures, longer hospital stays, higher inpatient charges, and are more likely to be transferred to other health care facilities after a hospitalization.

In light of the importance health systems have attached to cost efficiencies and improved care utilization, we need to do a much better job of identifying older patients at high risk for epilepsy, and designing comprehensive care models to improve their outcomes and prevent readmissions. We are fortunate to have early career faculty in our Department of Neurology who are focusing on this important area of care, such as Leah Blank, MD, MPH, whose research addresses how to improve the implementation of best practices in older adults with epilepsy.

“Older patients with epilepsy have more falls and fractures, longer hospital stays, higher inpatient charges, and are more likely to be transferred to other health care facilities...”

– Nathalie Jetté, MD, MSc

Q. What type of models do we need to create to ensure optimal treatment and care for older adults with epilepsy?

Dr. Jetté: Our studies suggest that strategies to improve transition of care have the potential to reduce readmissions in this patient population. For example, in one of our studies co-led by epilepsy fellow Cristina Schreckinger, MD, we propose that hospital discharge planning is an area where health care systems can do a better job. Improvements to consider include follow-up phone calls to the patient soon after discharge, inclusion of caregivers in discharge planning, and better coordination with outpatient follow-up care to ensure that prescriptions are being filled, for example, and that patients have a support network in place.

“From a clinical standpoint, we need to give health care providers better tools to identify and stratify high-risk older patients to prevent readmissions due to epileptic seizures and infections...”

– Nathalie, Jetté, MD, MSc

New models should also provide for continuous assessment and evaluation of the functional and social status of patients, and for implementing practices focused on patient safety and risk mitigation.

Research at Mount Sinai has demonstrated that a follow-up program driven by transitional-care nurses resulted in significant reductions in 30-day readmissions in patients over 65 at several hospitals. From a clinical standpoint, we need to give health care providers better tools to identify and stratify high-risk older patients to prevent readmissions due to epileptic seizures and infections—two common causes of readmissions in older adults with epilepsy.

Q. Who is responsible for creating new care models for people with epilepsy?

Dr. Jetté: All key stakeholders should be playing a role. They include hospitals, neurologists and other physicians, government, and health system policymakers who help ensure patients have the services they need, and the research community itself. We must push for clinical trials that are more inclusive of older people with epilepsy, realizing they are huge users of health services and that their numbers are growing rapidly. It’s challenging to get funding for studies involving older people with epilepsy, but these trials are essential if we’re going to curtail the cost of health care and make sure we have the right resources in place to help these vulnerable populations.

There are many misconceptions around the risk of epilepsy surgery.

Q. What has your research uncovered about the use of epilepsy surgery in patients who are resistant to anti-seizure medications?

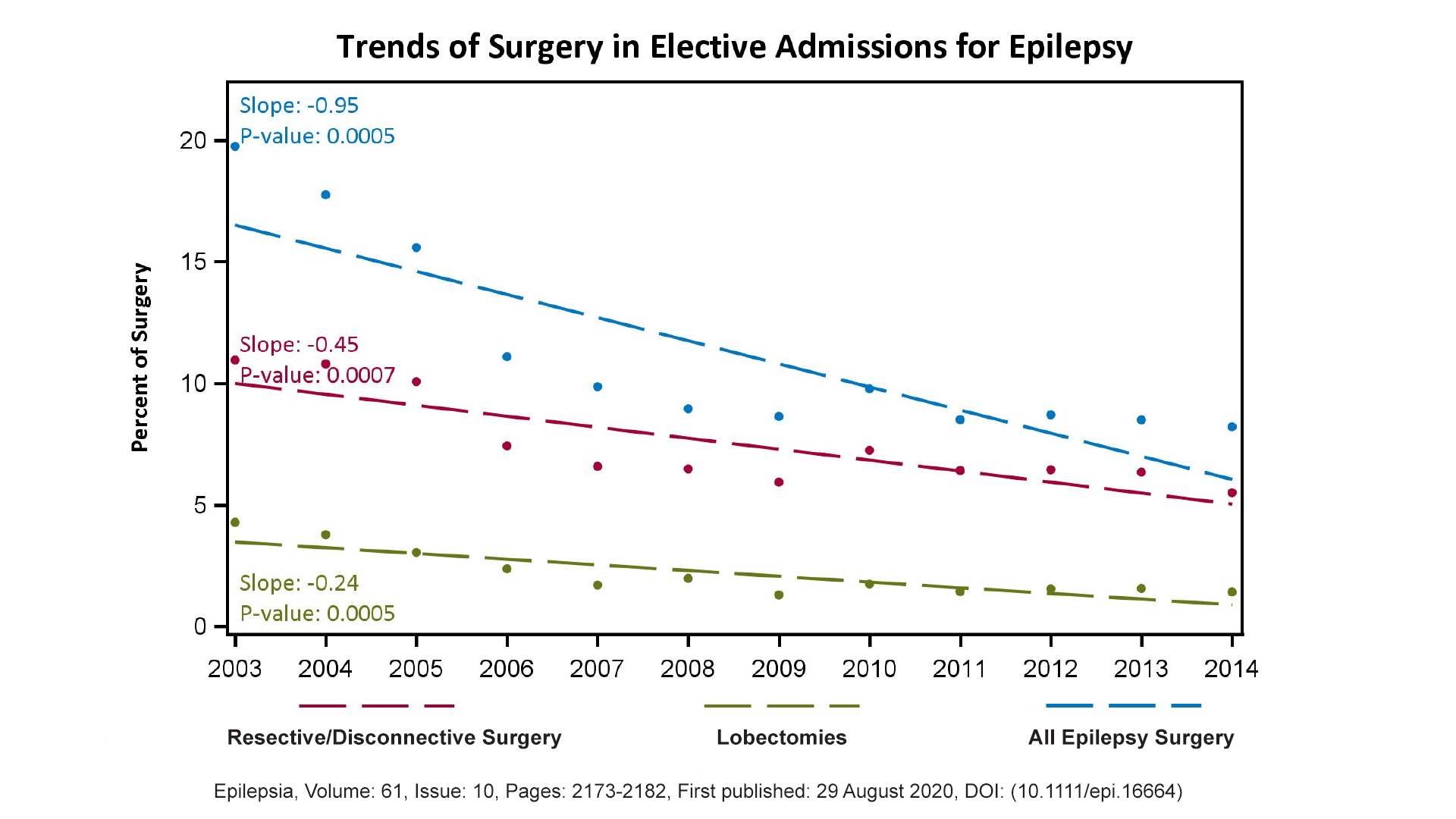

Dr. Jetté: One of our studies, co-led by Churl-Su Kwon, MD, MPH, Assistant Professor of Neurology, and Neurosurgery, found that despite national guidelines supporting surgical referral in drug-resistant epilepsy, the number of temporal lobectomies—the most common surgery in people with epilepsy—continues to decrease, suggesting underutilization.

What makes this trend disturbing is that it’s occurring in the face of substantial evidence of the efficacy of temporal lobectomy. One major study showed that 73 percent of those who underwent surgery were seizure-free at two years, compared to 0 percent of those treated with medicine alone.

Many other studies have also confirmed that surgery for patients who have failed at least two anti-seizure medications is both safe and effective. Furthermore, this decline in resective epilepsy surgery nationally is not explained by an increase in minimally invasive surgery (for example, responsive neurostimulation, or later interstitial thermal therapy), suggesting ongoing underutilization of epilepsy surgery in the United States.

Trends of Surgery in Elective Admissions for Epilepsy

Trends of surgery in elective admissions for epilepsy as a percentage of all primary epilepsy discharges comparing lobectomies and amygdalohippocampectomies, versus resective and disconnective surgeries versus all epilepsy surgery types.

Q. Why, then, is surgical intervention underutilized in patients who could benefit from it?

Dr. Jetté: For one thing, there are many misconceptions around the risk of epilepsy surgery, as discussed in one of my earlier articles. Patients tend to believe it’s dangerous—even more dangerous than having ongoing seizures. We know that’s not the case. Even if they have three convulsive seizures a year, their odds of dying of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy are increased fifteen-fold.

Also, there are so many anti-seizure medicines available today that neurologists and other providers will often try one after another, even though published evidence shows that individuals who fail two anti-seizure medicines are not likely to respond to further agents and, if they do, the benefit is often not sustained. Surgery becomes a last resort for these physicians, when in fact, it should be considered after failure of two anti-seizure medications. There are other roadblocks to epilepsy surgery, including cultural barriers and financial barriers, especially for patients from minority and lower-income groups, as well as people on Medicaid.

Q. How can these obstacles and misconceptions be removed?

Dr. Jetté: The best way is through better education—for both patients and physicians. I’m currently leading the International League Against Epilepsy Standards and Best Practice Council and we have been developing consensus recommendation on when to refer patients for an epilepsy surgery evaluation. We have developed guidance on criteria for pediatric epilepsy surgery centers of care. We are also developing algorithms that will help providers identify those with drug resistant epilepsy in electronic health records.

Q. What are some of the lessons that neurologists can take away from the research that you and others at Mount Sinai have conducted on epilepsy?

Dr. Jetté: Above all, we need to constantly evaluate the care we provide to our patients. There are so many things we can be doing for people living with epilepsy, including introducing new therapies (for example, increasing the utilization of minimally invasive surgical therapies such as responsive neurostimulation or laser interstitial thermal therapy), managing comorbidities such as depression, and initiating presurgical evaluations for appropriate candidates. I believe that providers also need to be humble in their approach and refer their patients to comprehensive epilepsy centers if they are not improving, especially if they continue to have seizures after trying two anti-seizure medications. Our team and others have shown that referral to epilepsy providers is associated with a lower risk of premature mortality.