The decision to start a family can be fraught with emotion, anxiety, and uncertainty for couples who decide to pursue in vitro fertilization (IVF) therapy. When the birthing partner happens to have chronic liver disease, as growing numbers across the country do, the stress is only multiplied as they weigh the implications their condition might have on the ability to conceive as well as the health of their newborn.

A breakthrough study from researchers at the Institute for Liver Medicine at Mount Sinai may finally allay many of those fears. The study, published in the American Journal of Gastroenterology, found that, in women with liver disease who underwent standard IVF treatment, there was no statistically significant differences in the rates of conception, pregnancy loss, or live births compared to women without liver disease.

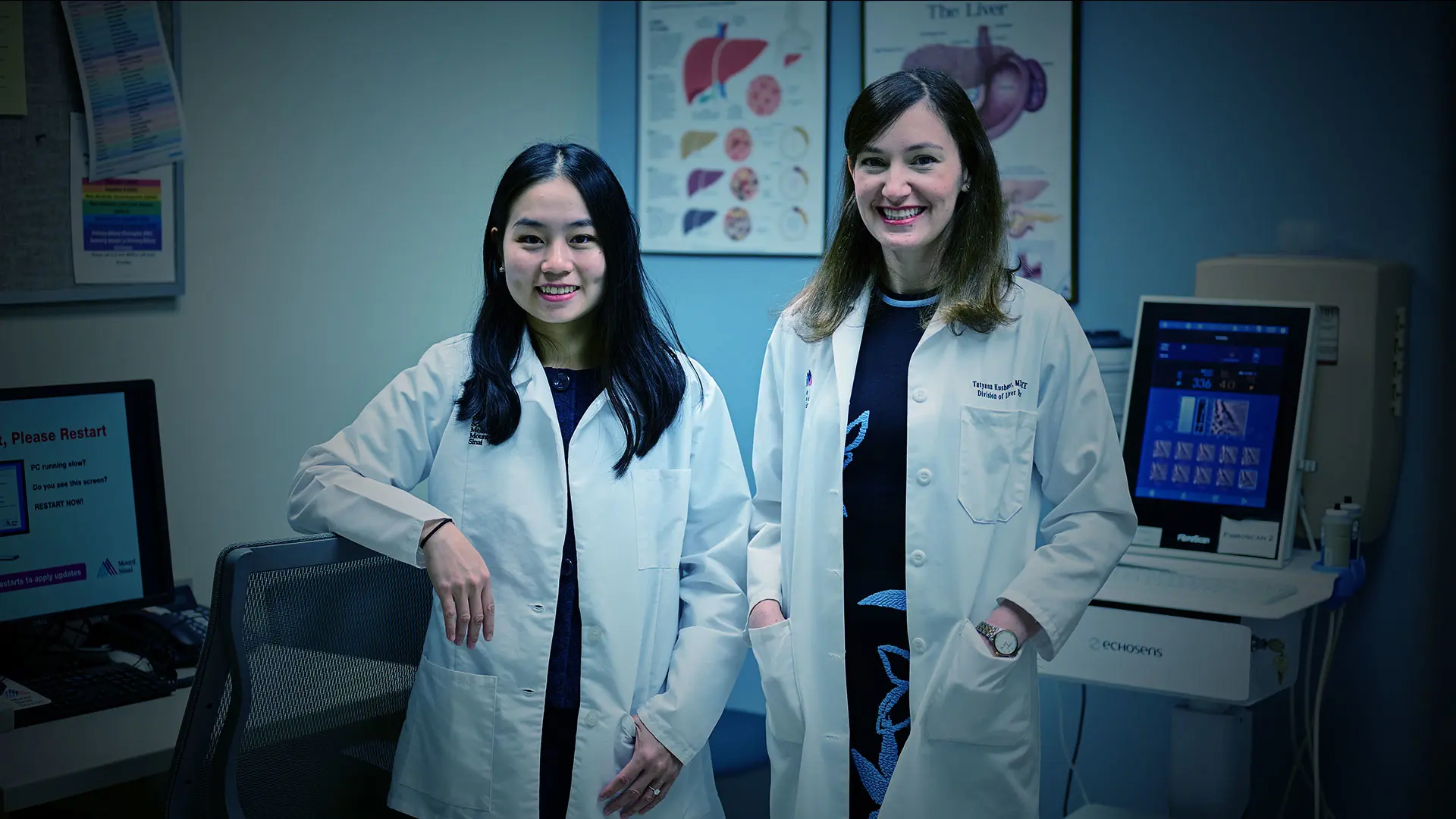

“As the prevalence of liver disease continues to grow in women of reproductive age, we realized how important a study of this type would be to clinically assess and counsel patients we see in our clinic about what to expect when pursuing IVF,” says Tatyana Kushner, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine (Liver Diseases), and Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and a hepatologist in Mount Sinai’s Institute for Liver Medicine. “Our findings are very positive and reassuring for these women and reinforce that a diagnosis of chronic liver disease such as hepatitis B or C should not cause delays in the IVF counseling or treatment they receive from health care professionals.”

Women with chronic liver disease may experience impaired fertility, which is why IVF—considered a form of assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment—can be an integral part of their reproductive management. In 2018, 2 percent of infants born in the United States were conceived through ART, with IVF being the most common procedure. Research into ART treatment outcomes in women with liver disease has been limited, however, to several studies from East Asian countries and a single European retrospective study that did not necessarily reflect contemporary IVF protocols.

The Mount Sinai study looked at 295 women with liver disease treated at Reproductive Medicine Associates of New York, the high-volume fertility treatment center affiliated with the Mount Sinai Health System, which worked closely with Dr. Kushner and her team. The vast majority of participants had viral hepatitis B or C, while smaller numbers had nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, cholestatic liver disease, or cirrhosis, or had undergone liver transplants. In each case, standard IVF treatment included obtaining an embryo biopsy and cryopreservation before undergoing single-embryo transfer with a thawed euploid embryo, then comparing the outcomes to those of women without liver disease who underwent the same treatment.

The research team found no significant difference between the two cohorts in terms of the rates of clinical pregnancy, clinical pregnancy loss, or live births. The only measurable difference the study reported was that liver disease patients had fewer oocytes during egg retrieval and subsequently fewer mature oocytes, fertilized embryos, and euploid embryos compared to the control group, although when adjusted for relevant factors such as population age there was still no significant difference in outcomes.

Jessica Lee, MD, and Tatyana Kushner, MD

“These findings send an important message to women with liver disease who may delay starting a family because they believe they must first get their liver condition under control, or that there might be a liver disease-related risk associated with having a child,” notes Jessica Lee, MD, who was first author on the study as a medical student at Icahn Mount Sinai. “The message is that there’s no need for them to postpone counseling about their fertility preservation options, and that it should start earlier rather than later in their family planning process.”

Dr. Kushner believes the study’s findings are no less critical for informing the wide range of professionals involved in reproductive counseling and care for women with liver disease, including hepatologists, obstetricians, gastroenterologists, endocrinologists, and primary care physicians.

“There tends to be too little interdisciplinary communication among these groups,” she notes, “but it’s clear we need to work collaboratively to provide the best possible evidence-based counseling and ongoing care to these patients at a very important time in their lives.”

Featured

Tatyana Kushner, MD

Associate Professor of Medicine (Liver Diseases), and Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Science

Jessica Lee, MD

Former medical student, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai