U.S. policymakers are increasingly focused on curtailing Medicare hospice services for people with dementia due to increasing hospice benefit expenditures. A new joint study by researchers at the Brookdale Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) may prompt them to take a second look.

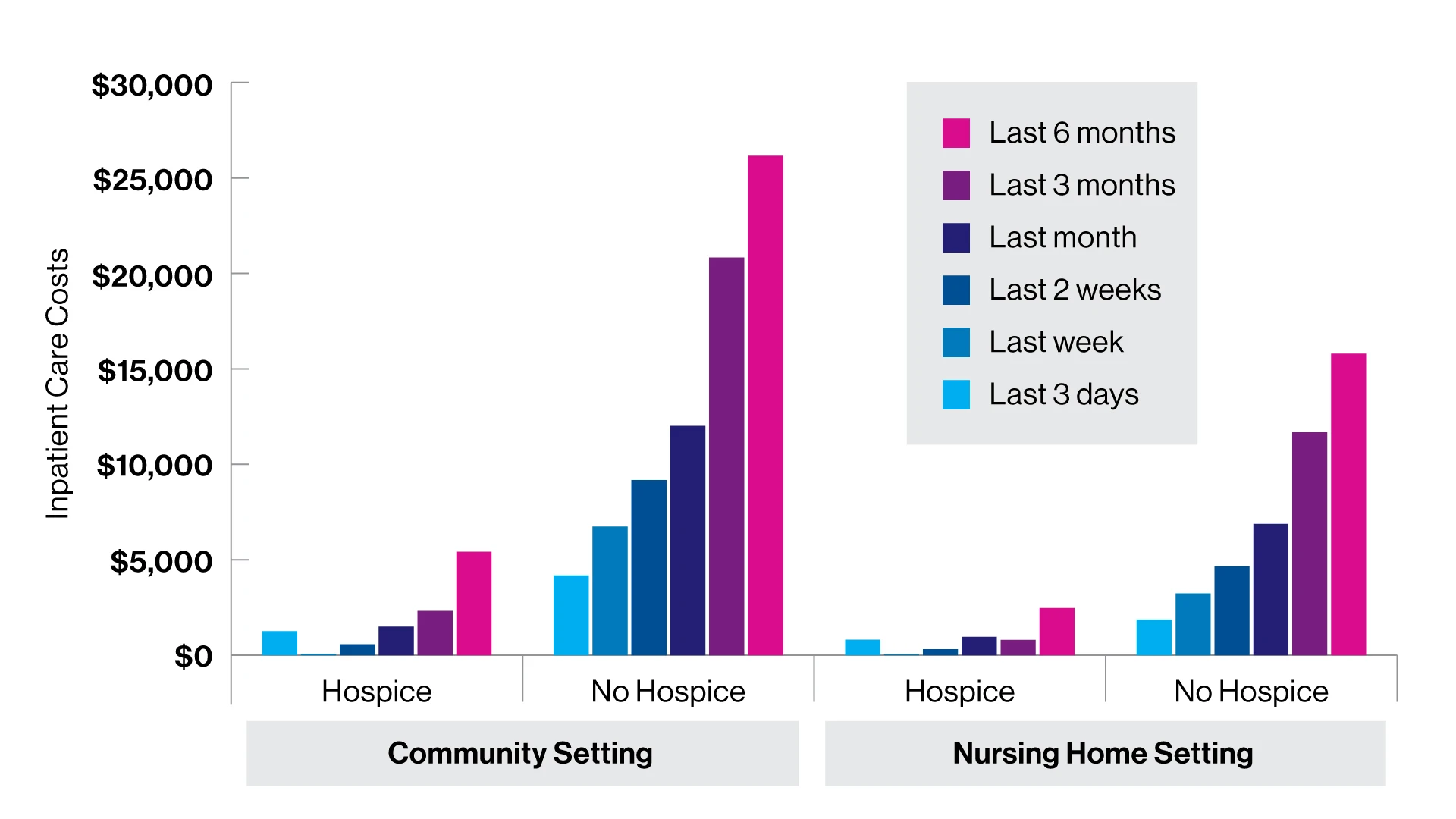

The findings, published in September 2023 in Health Affairs, reveal that Medicare costs for community-dwelling individuals with dementia who used hospice services were lower than for those who did not—whether hospice enrollment was in the last three days or the last three months of life—primarily through the avoidance of inpatient care costs in the last days of life.

“When Medicare puts pressure on hospice providers for having patients who are enrolled with hospice for long periods of time, disenrollment from hospice can increase, and this often results in poor quality outcomes for patients and families,” says Melissa Aldridge, PhD, Professor and Vice Chair of Research at the Brookdale Department and lead author of the study. “Our work shows Medicare policies that reduce hospice access or incentivize hospice disenrollment are likely to actually increase Medicare costs since hospice cost savings generally derive from a person’s last days or weeks of life.” Hospice disenrollment is known to occur in an estimated 13 to 16 percent of patients with dementia.

Spending for inpatient care for people with dementia in community and nursing home settings in the United States, by hospice use, 2002–19.

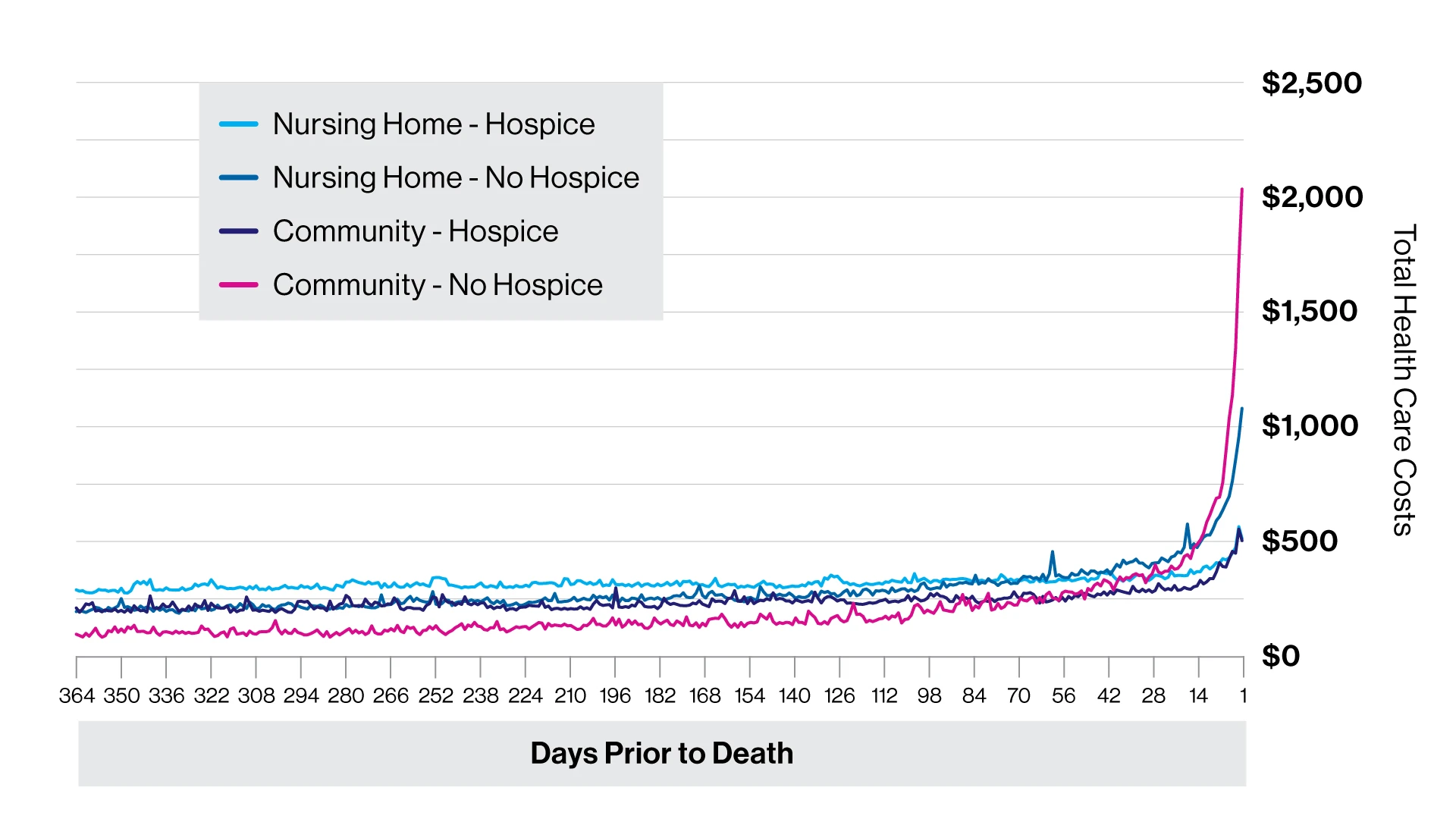

Daily unadjusted total health care costs in the last year of life for people with dementia in community and nursing home settings in the United States, by hospice use, 2002–19.

Fueling the Mount Sinai-UCSF research project is a prestigious five-year grant from the National Institute on Aging to explore coexisting medical, social, and health system factors that affect people with dementia, and their families. One of the first studies to emerge from the project in June 2022 found that hospice significantly improves the quality of life for older adults with dementia in their last year of life and, as such, underscores the need to ensure access to this vital service for patients and their families.

Putting the issue in context is the fact that hospice has become the dominant end-of-life care model for people with dementia. Indeed, more than half of all hospice enrollees in the United States have dementia, making them the fastest-growing segment of hospice users.

The combination of rapidly growing hospice use and longer hospice stays has led to increased scrutiny in recent years by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), according to the recent study. One consequence was Medicare’s 2016 reform intended to discourage longer durations of hospice care by reducing per diem payments to hospice facilities after 60 days of care. Moreover, CMS continues to enact policies and procedures designed to mitigate the rising cost of Medicare hospice benefits, according to researchers, while it urges consideration of alternative models for late-stage dementia care.

Against that backdrop, the Mount Sinai-UCSF team conducted a retrospective cohort study of Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) participants who had dementia and died during the period 2002 to 2019. They found that for those who received hospice care for three to six months before death, savings were more than $8,000 per person, the bulk of which accrued to Medicare, which spent approximately $7,000 less per hospice enrollee.

“Similar to patients with other serious illnesses, people with dementia incurred lower costs primarily due to the reduced expense for inpatient hospitalization in the last 7 to 10 days of life,” says Dr. Aldridge, whose research focuses on patterns of hospice use and end-of-life transitions in care. “In fact, the last days of life are when the most substantial cost differences between those with and without hospice become most apparent.”

A key implication of the study is that Medicare policy reforms such as the 2016 restriction on hospice reimbursement, along with a hospice aggregate cap, may be counterproductive to the goal of containing health care costs.

“When Medicare puts pressure on hospice providers for having patients who are enrolled with hospice for long periods of time, disenrollment from hospice can increase, and this often results in poor quality outcomes for patients and families,” says Melissa Aldridge, PhD, Professor and Vice Chair of Research at the Brookdale Department and lead author of the study.

“We showed that once a person with dementia is enrolled with hospice, it’s economically advantageous for them to remain enrolled until death to avoid costly hospitalizations in the last week or weeks of life,” says senior author R. Sean Morrison, MD, Ellen and Howard C. Katz Professor and Chair of the Brookdale Department. “Our study is also the first to suggest that hospice disenrollment significantly increases not just Medicare costs but out-of-pocket expenditures for family members compared to patients who remained in hospice or never enrolled in hospice at all.”

In light of their newest revelations, Mount Sinai and UCSF investigators reported in the study that they found “troubling” ongoing efforts by Medicare to reduce hospice access for those with dementia.

“People with dementia and their families benefit from the home-based interdisciplinary support that hospice provides,” says Dr. Aldridge. “As our research clearly implies, the focus of policymakers shouldn’t be on penalizing long-stay dementia patients, but rather on finding ways to make hospice care moreavailable to them given the overall cost savings to their families and to the U.S. health care system.”