Related Article

In the face of hepatitis B virus (HBV) levels in New York City significantly above the World Health Organization’s acceptable standard, Mount Sinai has responded with an initiative aimed at universal surveillance and vaccination of adults. As part of that effort, in August 2022 it launched a system of digital alerts that appear on the screens of primary care physicians when a patient in their offices is a candidate for testing, vaccination, or treatment for hepatitis B.

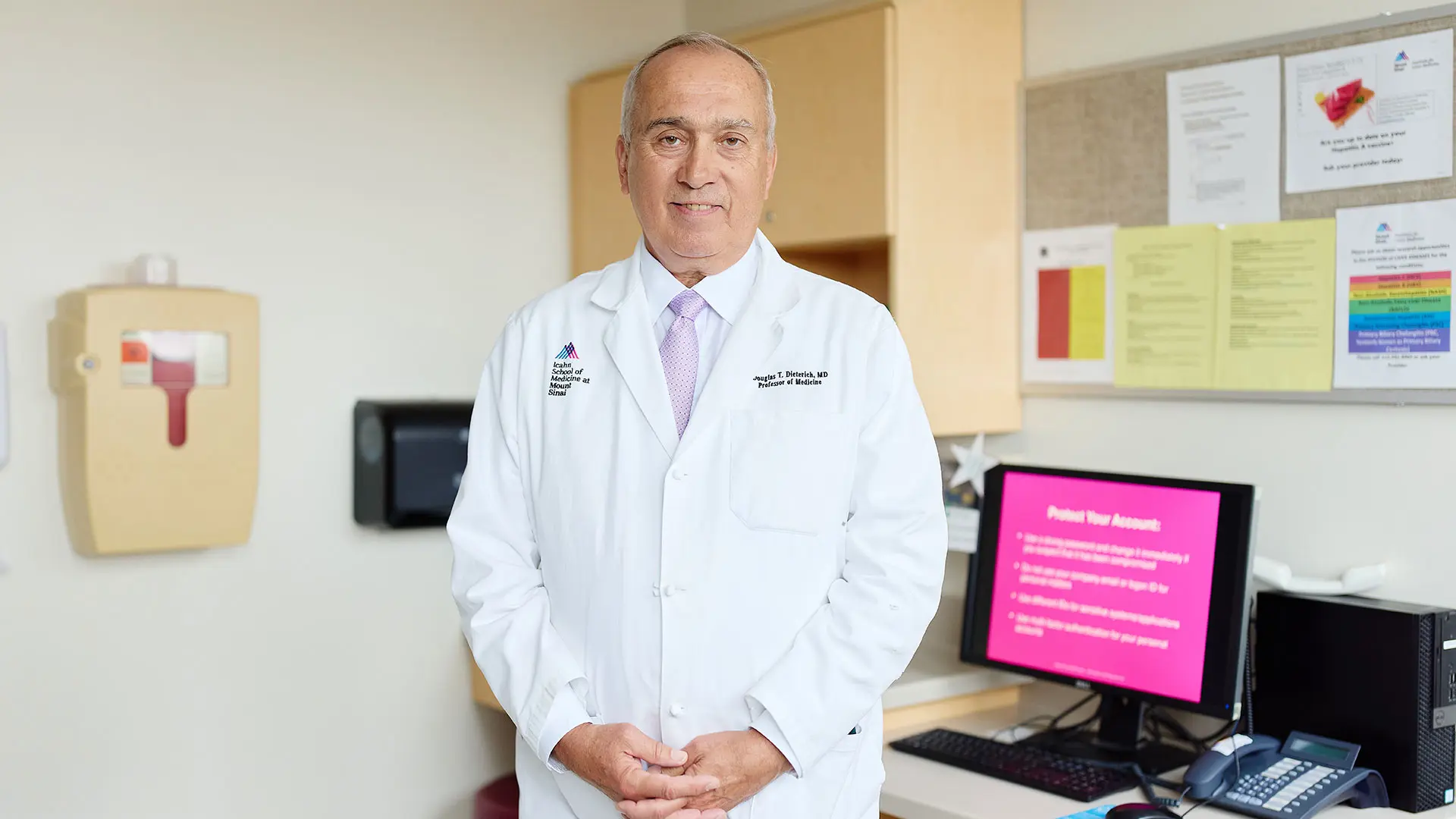

“If our laboratory records show no hep B or C serology results for a patient, then the primary care providers can simply click on their screens to order the right tests and learn how to interpret them,” says Douglas Dieterich, MD, Director of the Institute for Liver Medicine, which has responsibility for liver care across the Mount Sinai Health System.

“If the results are negative, vaccination would be the appropriate next step to help the patient acquire lifelong immunity,” Dr. Dieterich, Professor of Medicine (Liver Diseases) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, adds. “If the surface antigen is positive, however, we want to encourage the patient to seek treatment through our Institute for Liver Medicine and, if appropriate, offer them a clinical trial that’s focused on a cure.” A team of navigators is available to help patients with care coordination, Dr. Dieterich adds.

In New York City, public health authorities have estimated there are 241,000 individuals with chronic hepatitis B, of whom 46 percent are undiagnosed. Many children were vaccinated by pediatricians starting in 1991 as part of a nationwide effort, but because older teenagers were often missed, a sizable number of adults today never received protection.

Adding urgency to the vaccination and surveillance movement is the upsurge in New York City and the country of the highly contagious hepatitis Delta virus (HDV), a small RNA virus that uses the same receptor as hepatitis B to enter the liver cell and requires infection with hepatitis B to replicate.

“We want to test for Delta in everyone who tests positive for hepatitis B,” notes Dr. Dieterich. “Delta is the most severe form of viral hepatitis, and we know there are many people in New York who are carrying the virus. It can progress to cirrhosis within five years and to hepatocellular carcinoma within 10 years and has an extraordinarily high mortality rate.” The good news, he adds, is that several drugs could soon be approved for treating the Delta virus, including one that has worked very well in Europe for the past three years.

Douglas Dieterich, MD, is leading an effort to test all Mount Sinai primary care patients for hepatitis B and the related hepatitis Delta virus.

Against that backdrop, Mount Sinai is doubling down on its goal of eliminating both hepatitis B and hepatitis C. A program of universal screening and treatment for hepatitis C, rolled out by Mount Sinai in 2015, is now returning to its prepandemic volumes. Moreover, it has been broadened to include hepatitis B and Delta. Also returning to full strength is Mount Sinai’s Hepatitis Outreach Network (HONE), which goes into the community to conduct hepatitis B and C screening events, then link individuals who test positive to specialized care. According to Dr. Dieterich, HONE is being expanded beyond the African immigrant community to include Chinese, Russian, and Latinx populations in New York City.

Significantly, a cure already exists for hepatitis C infection thanks to several U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved direct-acting antivirals that work in different ways to prevent the virus from making copies of itself. For hepatitis B, Mount Sinai is part of several clinical trials that are making progress toward finding a “functional cure,” defined by the FDA as undetectable hepatitis B virus surface antigens (HBsAg) of less than 0.05 international units per milliliter.

Among those studies is a phase 1b trial of a core inhibitor of hepatitis B (from Assembly Biosciences) that has shown increased potency against covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) formation, thus blocking delivery of the genetic code needed to build new viruses. Another clinical study involves a monoclonal antibody (from Vir Biotechnology) that neutralizes hepatitis B virus and has been engineered to also potentially act as a therapeutic vaccine. This investigational drug is designed to block entry of all 10 genotypes of HBV into hepatocytes, while reducing the levels of virions and subviral particles in the blood.

“We’re certainly encouraged by the many new drug candidates on the horizon,” emphasizes Dr. Dieterich, “and the role they could potentially play along with aggressive surveillance and treatment of hepatitis B and C to bring these viruses under control, if not prevent them from ever occurring.”

Featured Faculty and Division Leadership

Douglas Dieterich, MD

Professor of Medicine (Liver Diseases); Director, Institute for Liver Medicine

Meena Bansal, MD

Professor of Medicine (Liver Diseases); System Chief, Division of Liver Diseases