While T cells have received abundant attention from scientists probing the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis (UC), B cells—a major component of the adaptive immune system—have remained largely unstudied in this context. Mount Sinai-led researchers acting to fill that void have discovered for the first time a highly dysregulated B cell response in UC that opens the door to potential new biomarkers and therapeutic strategies for UC, as well as other types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The team’s findings were reported in Nature Medicine.

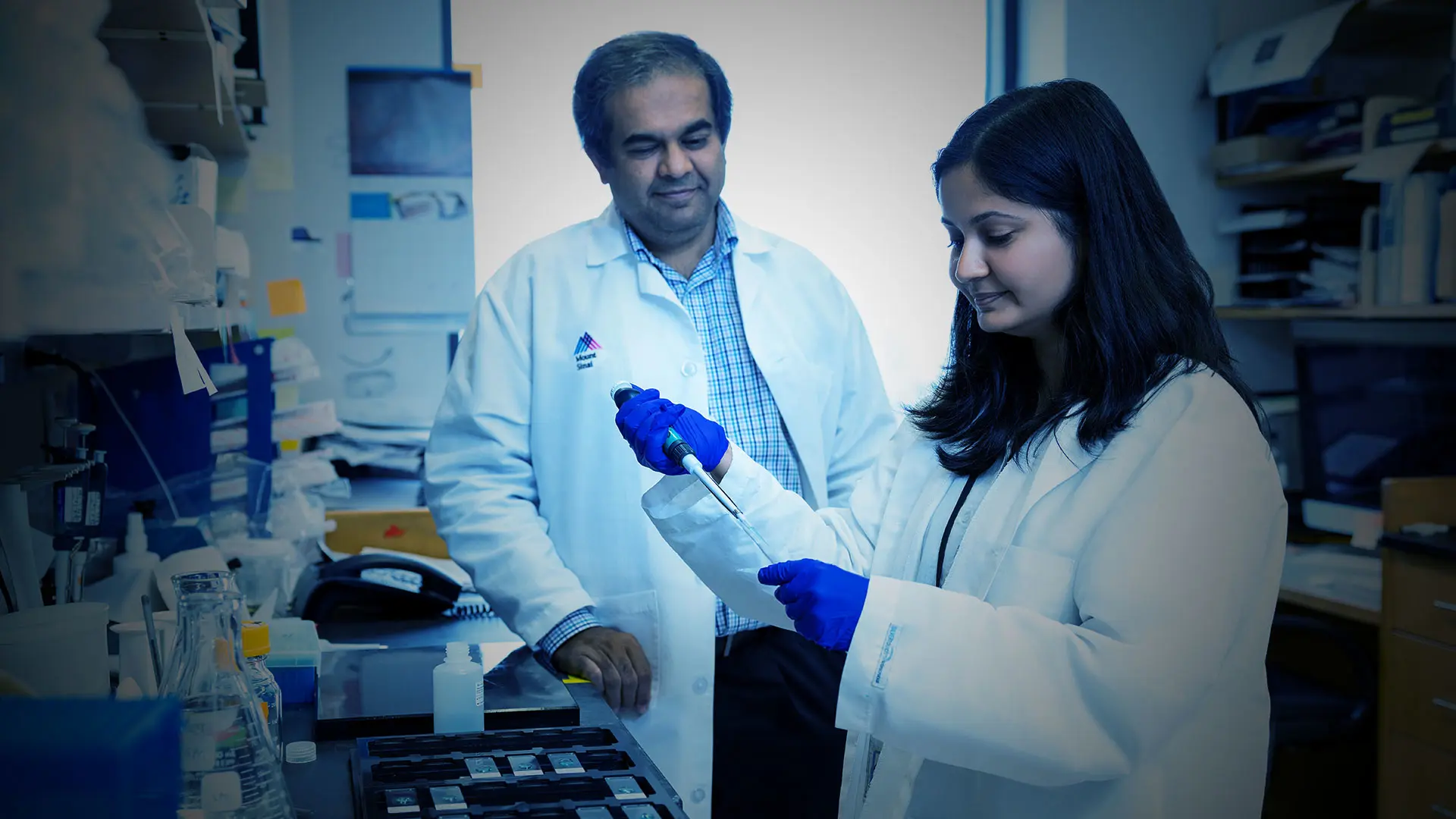

“We’ve begun to define the landscape of B cells during UC-associated intestinal inflammation, and found major perturbations within the mucosal B cell compartment,” says Saurabh Mehandru, MD, Professor of Medicine (Gastroenterology) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and senior author of the study. “These changes include a significant expansion of naïve B cells and IgG+ plasma cells, along with an expansion of gut-homing plasma cells that correlate with disease activity and predict disease complications.”

With their sights set on the origins of the dysregulated B cell response to ulcerative colitis, the researchers surfaced some important new findings about IgG+-producing plasma cells that have been identified in the diseased intestinal mucosa. Though less common than IgA-producing plasma cells (which promote tolerance at mucosal surfaces), IgG+ plasma cells potentially enhance inflammation in UC while reacting to the invading pathogens.

A case in point highlighted by the Mount Sinai team is a population of interferon (IFN)-primed naïve B cells that expands in UC and is associated with an increased frequency of IgG+ plasmablasts and IgG+ plasma cells. “We found within a module naïve B cells that were potentially associated with IgG+-producing plasma cells,” explains Dr. Mehandru. “That gives us an important window into why IgG+ plasma cells may potentially be increased in UC.”

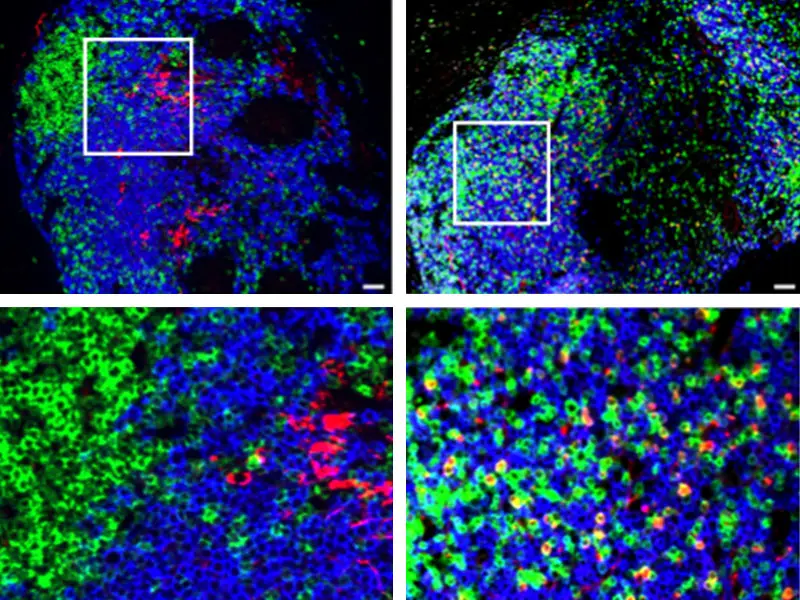

Representative images from a healthy control (left) and a patient with ulcerative colitis (right), highlighting the presence of CXCL13-producing T cells in ulcerative colitis. T cells are indicated by CD3 (green), B cells by CD20 (blue), CXCL13 is shown in red, and DAPI (for cell nuclei) is in grey.

Another example of the magnitude and breadth of immune perturbations in UC is the discovery of the protein CXCL13, which is produced by T cells in the inflamed intestine, and the suggestion by researchers that targeting these T cells, or CXCL13 itself, might help reduce the production of pathogenic plasmablasts and thus attenuate colonic inflammation. “We’re quite encouraged by this finding, but realize that more research is needed to confirm CXCL13 as a viable target,” states Dr. Mehandru, who has led the Mucosal Immunology Laboratory at Mount Sinai since 2013. The lab is involved in human-focused mucosal immunology research that includes mucosal trafficking, the host-pathogen interface in health and inflammation, and the impact of primary and acquired immunodeficiency states on mucosal cells.

In addition to CXCL13+ T cells, Dr. Mehandru’s team detected a population of inflammatory macrophages expressing CXCL9—an IFN-induced gene that serves as a selective ligand for CXCR3—in the inflamed UC colon. In line with that, they found a significant expansion of intestinal CXCR3-expressing plasma cells in patients with UC. “Taken together,” says Dr. Mehandru, ”these data provide compelling evidence for type 1 immunity as a driver of naïve B cell molecular imprinting as well as skewing of acute B cell responses toward IgG+ production in the intestines of people with ulcerative colitis.”

On a broader scale, Dr. Mehandru believes his team’s research has begun to identify the biology and mechanisms behind B cell dysregulation—a breakthrough that could lead to promising therapeutic targets designed to help millions of people worldwide who experience ulcerative colitis and IBD.

From left: Julia Jougon, MD, visiting gastroenterologist; Divya Jha, PhD, postdoc; Daniel Dai, visiting student; Hadar Meringer, MD, postdoc; Saurabh Mehandru, MD; Alexandra Livanos, MD, PhD, instructor; Giana-Jochael Amissa, visiting student; Pablo Canales-Herrerias, PhD, postdoc; Michael Tankelevich, associate researcher

Featured

Saurabh Mehandru, MD

Professor of Medicine (Gastroenterology)