Neutralizing antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 develop in most individuals after infection, but then decay over time. Early in the pandemic, that dynamic posed for medical science a question of no small consequence for humans: are those antibodies of sufficient potency and durability to protect them from viral reinfection?

Researchers from Mount Sinai’s Dr. Henry D. Janowitz Division of Gastroenterology joined forces with the Laboratories of Molecular Immunology and Retrovirology at Rockefeller University to come up with an informed answer. The role of gastroenterologists was particularly important given that SARS-CoV-2 has a spike protein that tethers itself to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to gain entry to cells, and the intestinal tract has the highest expression of ACE2 in the body—even higher than in the lungs.

What the researchers found, they reported in Nature, was that the levels of IgM and IgG antibodies against the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein decreased over the 6.2 months after infection, with IgA antibodies being less affected. Taking up the defensive slack, however, are memory B cells, which evolve over that time frame to produce antibodies of increased neutralizing breadth and potency. Memory B cells are vital for not just protection from reinfection, but for effective vaccination.

“After an infection, a small subset of memory B cells are stored as ‘educated’ cells with the ability in the event of another infection to mount a rapid response against the SARS-CoV-2 virus,” explains Saurabh Mehandru, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine (Gastroenterology) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and a corresponding author of the study.

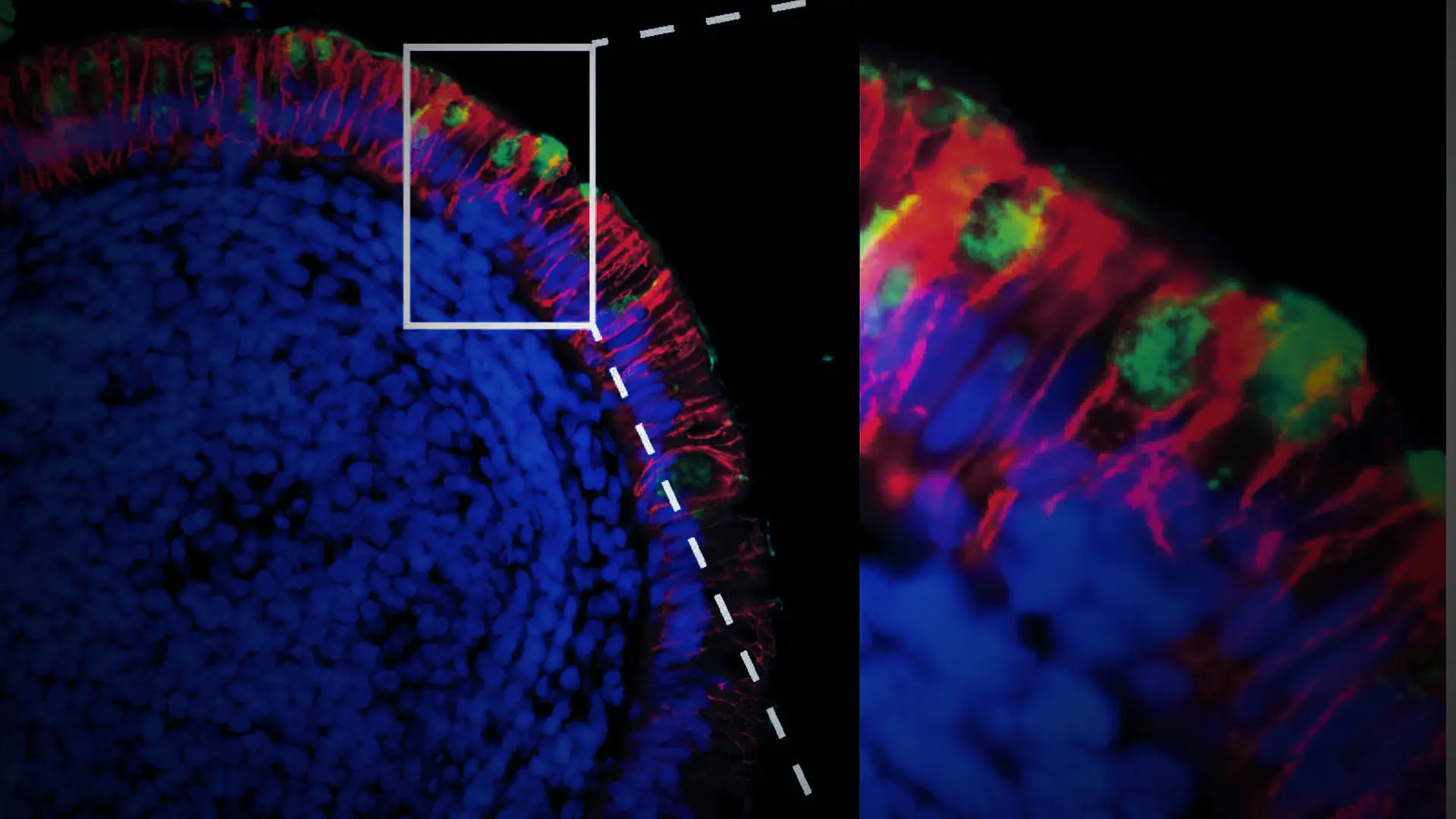

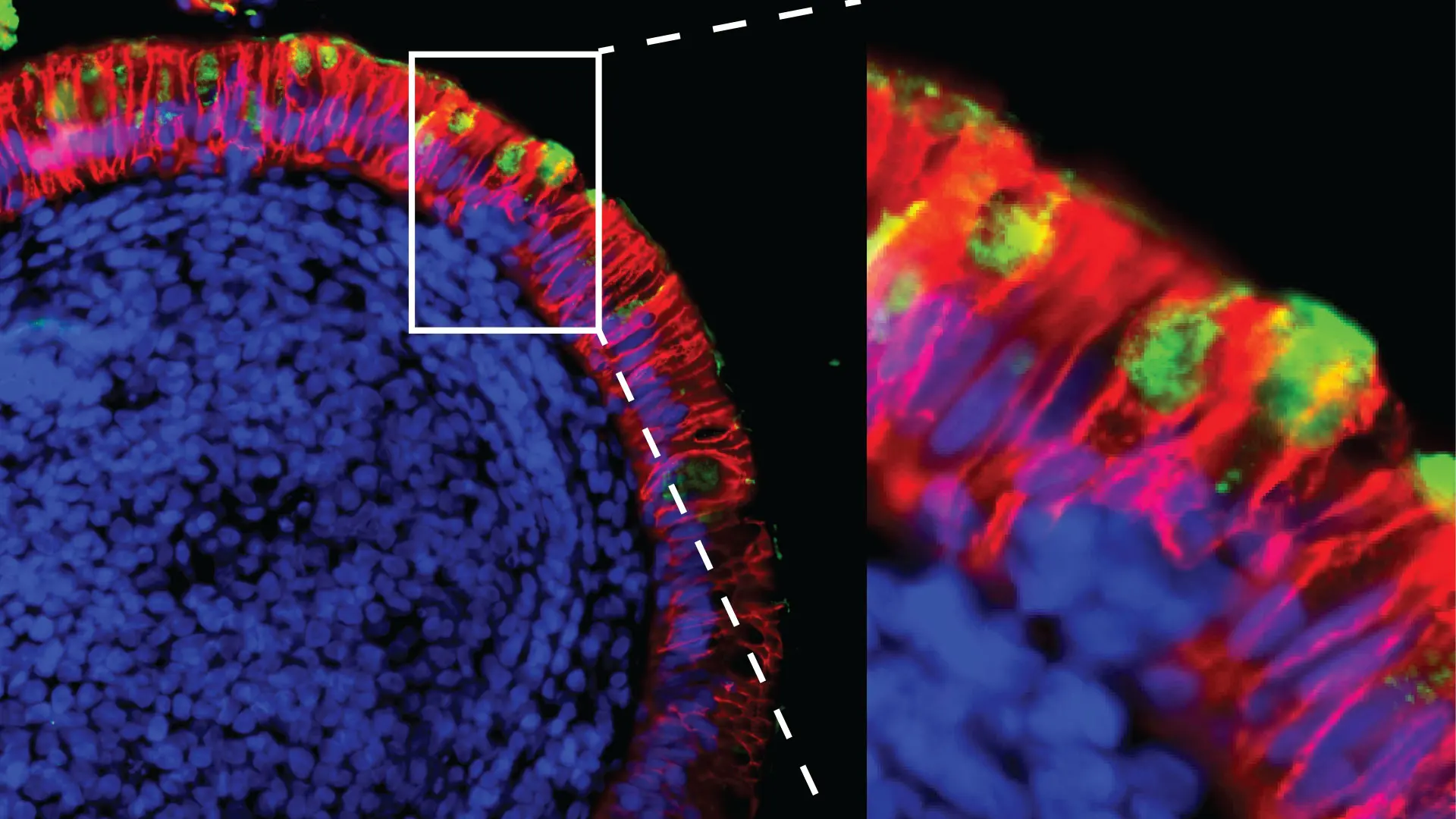

The study provided further evidence of the persistence of the virus in the gut. Analysis of intestinal biopsies from asymptomatic individuals at four months after the onset of COVID-19 revealed, for example, the presence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA and immunoreactivity in the small intestines of 7 out of 14 individuals. It also showed that SARS-CoV-2 mRNA and protein remained detectable in the small intestinal epithelium in some individuals months after infection (see figure below).

Red indicates epithelial cells; green indicates SARS-CoV-2 mRNA.

Among the implications from these findings is that the continued presence of SARS-CoV-2 may enable the antibody response to become more specific to the virus. “Viral persistence may allow the immune system to fine-tune the antibody response, making it more effective,” explains Dr. Mehandru. “The downside, however, is that an ongoing viral presence may be associated with ‘long COVID,’ a condition that may impact up to a third of all COVID-19 patients with wide-ranging and long-term symptoms.”

Results from the Mount Sinai-Rockefeller University study have since spawned multiple clinical investigations to track the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in the body and to relate viral persistence to long-COVID symptoms.

Featured

Saurabh Mehandru, MD

Professor of Medicine (Gastroenterology)