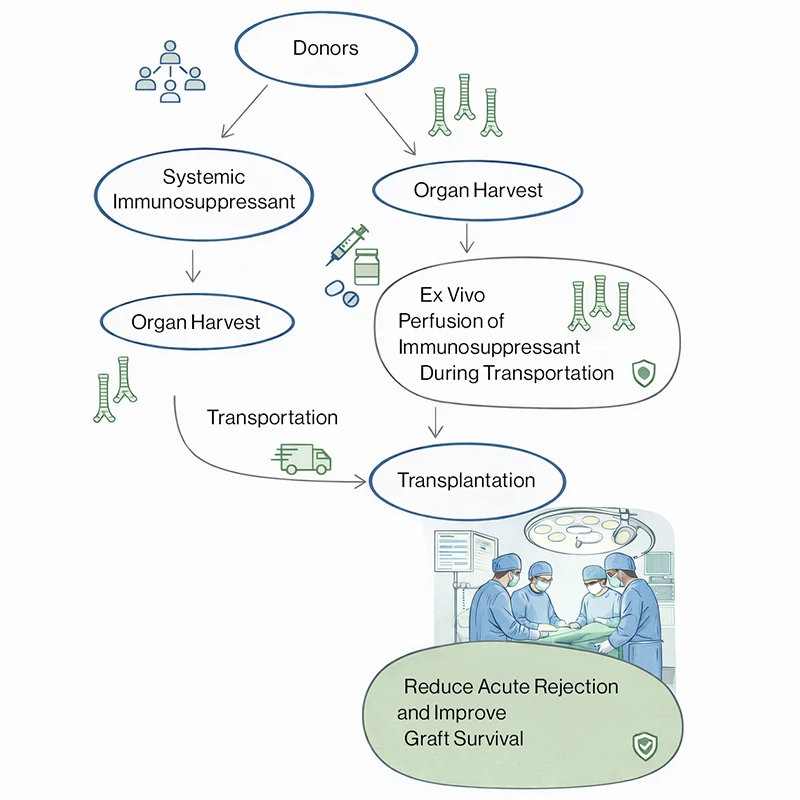

Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai are exploring whether giving immunosuppressant medications to organ donors—or perfusing organs with the drugs after they are harvested—could reduce rejection events for tracheal transplant patients.

“We have encouraging evidence from animal studies that this approach could benefit patients receiving a tracheal transplant and could, in theory, extend to other organ transplants as well,” says Ya-Wen Chen, PhD, Associate Professor of Otolaryngology, and Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, at the Icahn School of Medicine, who is leading the research.

Dr. Chen’s study was born from a major milestone for treating tracheal defects and injuries. In 2021, a team led by Eric M. Genden, MD, MHCA, FACS, the Isidore Friesner Professor and Chair of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery at the Icahn School of Medicine, performed the world’s first human long-segment tracheal transplant. Following decades of research, Dr. Genden’s team pioneered the use of a vascularized composite allograft (VCA) and associated blood vessels to replace a patient’s injured trachea with one from a deceased donor.

The 18-hour tracheal transplant procedure involved a team of more than 50 specialists that included surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, and residents. In this video, Eric M. Genden, MD, MHCA, FACS, and Sander S. Florman, MD, describe the events leading up to and during the procedure.

Such transplants could be lifesaving. Yet VCA transplants, which are more complex than single solid organ transplants, can experience acute rejection rates up to 85 percent, Dr. Chen says. While acute rejection can be managed, it increases the risk of chronic rejection and loss of the graft. After Dr. Genden’s landmark case, however, the inaugural trachea recipient did not experience any acute rejection—even after the gradual tapering of systemic immunosuppression.

The researchers noted two intriguing clues that might explain the surprising outcome. Histologic analysis of the transplanted trachea revealed the graft had been re-epithelialized with cells from the recipient, forming a chimeric tissue that blended donor and recipient cells. “We know epithelial cells are highly immunogenically active and play a central role in initiating and amplifying alloimmune responses,” Dr. Chen says. The robust re-epithelialization with recipient cells may have prevented such a response.

That process may have been related to a second important clue: The deceased donor of the tracheal tissue had been on immunosuppressive therapy for three years following a kidney transplant. “That observation made us wonder whether the donor’s immunosuppressed status could have contributed to the lack of acute rejection in the recipient,” Dr. Chen says.

Transplant Immunology in the Lab

To learn more, Dr. Chen first turned to mice bred to lack an adaptive immune system. She collaborated with microsurgeons who transplanted tracheae from those immunodeficient mice into mice with normal immune systems. Later, the team harvested the tracheae to see how the transplanted tissue was faring. “We found the immune condition of the donor had a notable influence on transplant outcomes,” she says.

Compared with a control group of transplants from immunologically normal donors, those from immunodeficient mice showed less immune cell infiltration, better epithelial integrity, and better graft morphology. “When there is acute rejection, we typically see the immune cells attack the tissue, which can cause the trachea to collapse. We didn’t see that in our mouse model,” Dr. Chen says.

In next steps, she is repeating the experiment using donor mice with normal immune systems that are treated with immunosuppressant medications, an experimental protocol that more closely mirrors the real-world case of Dr. Genden’s patient. The research is ongoing, but early findings suggest that, as hypothesized, preconditioning donors with immunosuppressant drugs may reduce immune cell infiltration and improve transplant outcomes.

Translational Research: Connecting the Dots to Human Transplant

Dr. Chen acknowledges there is more work to do before extending the findings to human transplantation. For example, most transplanted organs come from deceased donors, not living donors. That provides a challenge for treating them with immunosuppressants systematically.

Yet Dr. Chen says she is finding beneficial immune changes in donor mice after just 12 hours of immunosuppressant drugs. If the timeline in humans is similar, it might be possible to give medications to some patients following brain death to optimize their organs for transplant before they are removed from life support. “A lot of transplants fail early. Even if we can’t completely prevent rejection by preconditioning donors with immunosuppressants, reducing acute rejection could still benefit many patients,” she says.

Dr. Chen and her lab team are also studying whether perfusing an organ with immunosuppressant drugs after it is harvested might also reduce rejection—an approach that could expand the principle to many more organs, even those harvested from donors who die unexpectedly.

If so, such a breakthrough could change the field of transplant medicine. “I can envision a device that continuously perfuses the organ as it’s being transported and prepared for transplant,” Dr. Chen says. “If we can show that such treatments decrease organ rejection, it could have a major impact—not just for patients who need tracheal transplants, but for the entire transplantation field.”

Schematic illustrating two alternative immunosuppression approaches selected based on donor status: systemic immunosuppression of the donor prior to organ harvest, or ex vivo immunosuppressant perfusion of the tracheal graft during transport. Either strategy is followed by transplantation, with the goal of reducing acute rejection and improving graft survival. (Concept illustrated using generative AI.)

First, however, the team will continue the research in mice, exploring the mechanisms by which immunosuppression might improve transplant outcomes and discovering which immunosuppression regimens might be most effective. It is possible that different drugs might be used for treating living donors versus donors being removed from life support, she adds, or that different organs might require different drugs and dosages. “Once we figure out the potential mechanisms, we could design more targeted drugs to maximize the effects,” she says.

For now, Dr. Chen is cautiously optimistic about her preliminary findings and credits the innovative research to the close collaboration and respect between clinicians and researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine. “When I talk about this research, people think it sounds like a sci-fi story. But my colleagues and leadership at Mount Sinai are excited to support new ideas, no matter how sci-fi they sound,” she says. “There’s a rare passion here for translating research into clinical advances, and I’m hopeful this will lead to more effective transplants.”

Featured

Ya-Wen Chen, PhD

Associate Professor of Otolaryngology, and Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine