Immunotherapy has significantly impacted the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, but a subset of patients does not respond to the treatment. In translational research and clinical trials, researchers at the Head and Neck Institute at the Mount Sinai Health System are advancing the understanding of immunotherapy—and testing a new combination treatment with chemotherapy (chemoimmunotherapy) that holds promise for improving survival and quality of life.

“Immunotherapy has been the biggest breakthrough in head and neck cancer treatment in the last 20 years, but it doesn’t work for everyone. The question for the head and neck cancer community is how to optimize the benefit of immunotherapy treatments,” says Scott A. Roof, MD, Director of Clinical Research in the Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, and Assistant Professor, Otolaryngology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “We’re finding ways to make immunotherapy more effective, and it’s exciting that Mount Sinai is at the forefront of these discoveries.”

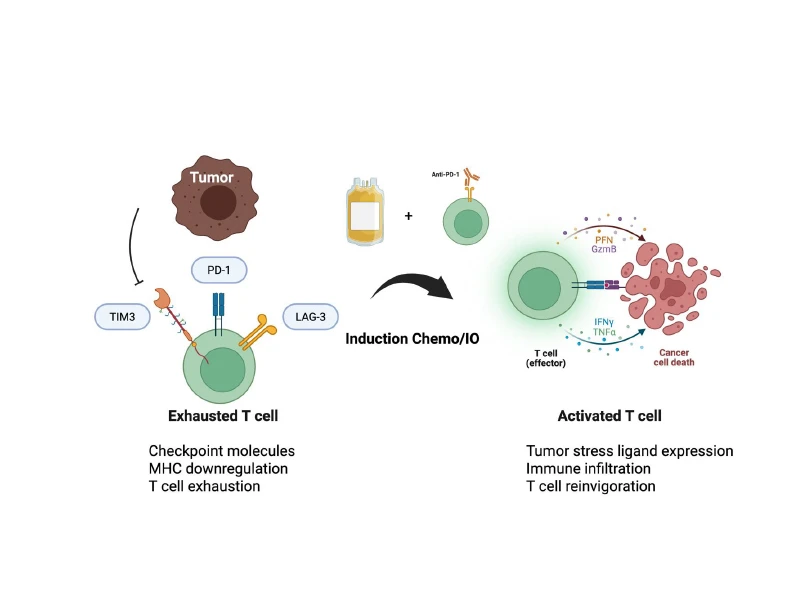

The research centers around immune checkpoint inhibitors, immunotherapy drugs that work by unmasking cancer cells so the immune system can recognize and destroy them. Immune checkpoint inhibitors were approved for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma after they were shown to significantly improve survival—first in people with recurrent and metastatic disease and now in patients with locally advanced cancer who received the immunotherapy before surgery.

A patient with lateral tongue squamous cell carcinoma before (left) and after (right) neoadjuvant induction chemotherapy, shown prior to surgery. Tumor response reduced the extent of surgical resection required and improved clinical outcomes.

Yet patient responses to immunotherapy can vary significantly. Immune checkpoint inhibitors seem to be most effective against head and neck tumors with active inflammation, which signals to the immune cells that something is wrong and attracts them to the area surrounding the tumor.

“The immune cells are waiting and ready to attack as soon as immunotherapy removes a cancer cell’s disguise,” Dr. Roof says.

However, two other groups of tumors do not seem to respond as effectively. One is a group of tumors where immune cells are present, but those cells are exhausted and no longer functioning normally. These patients may or may not respond to immunotherapy. In another group, the tumor has triggered little to no inflammation, so almost no immune cells are engaged in the tumor microenvironment. Unsurprisingly, these patients tend not to respond to immunotherapy treatments.

In these latter two groups, Dr. Roof and his colleagues theorized, it is possible to improve immunotherapy responses by recruiting more active immune cells to join the fight.

Visual representation of the tumor interacting with T cells after induction chemoimmunotherapy.

Encouraging Findings for Chemoimmunotherapy

To test that theory, Dr. Roof and colleagues, including Krzysztof J. Misiukiewicz, MD, Clinical Director of Research in Head and Neck, and the Center for Personalized Cancer Therapeutics, The Tisch Cancer Institute, and Associate Professor, Medicine (Hematology and Medical Oncology) and Assistant Professor, Otolaryngology, Icahn School of Medicine, conducted a phase 1 trial of induction chemoimmunotherapy in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. Before patients received standard-of-care treatment, they were treated with a combination of chemotherapy and cemiplimab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

The use of chemotherapy alone before definitive treatment, known as induction therapy, is not novel. As a standard of care, some patients receive chemotherapy to shrink a tumor before surgical removal. Dr. Roof and his colleagues hoped adding immunotherapy could increase the benefit. As chemotherapy kills cancer cells, it causes a great deal of inflammation, triggering a response that recruits immune cells to the tumor, the researchers reasoned. They hoped adding immunotherapy could prime those immune cells to aid in the attack.

Scott A. Roof, MD, (right), and Krzysztof J. Misiukiewicz, MD

As a phase 1 trial, the study was designed to test toxicity and safety. Patients tolerated the treatment well. While one patient experienced colitis, none experienced adverse events that prevented them from continuing with their surgery or additional scheduled treatments. The trial included just 24 patients, and follow-up data from the last participants is still being collected. While it is too soon to draw firm conclusions, Dr. Roof cautions, the outcomes have so far been striking.

About half of patients showed a major response, with the tumor shrinking at least 90 percent, Dr. Roof says. Almost 30 percent had a complete response. “We took the patients to the operating room to remove their tumors, and there was nothing left,” Dr. Roof says. By contrast, he says, only about 7-8 percent of patients who receive immunotherapy alone without chemotherapy typically have a complete response rate. Survival rates, too, look promising. To date, more than 70 percent of participants have surpassed the two-year disease-free survival point. “No one on our team has ever seen a response like this,” he adds.

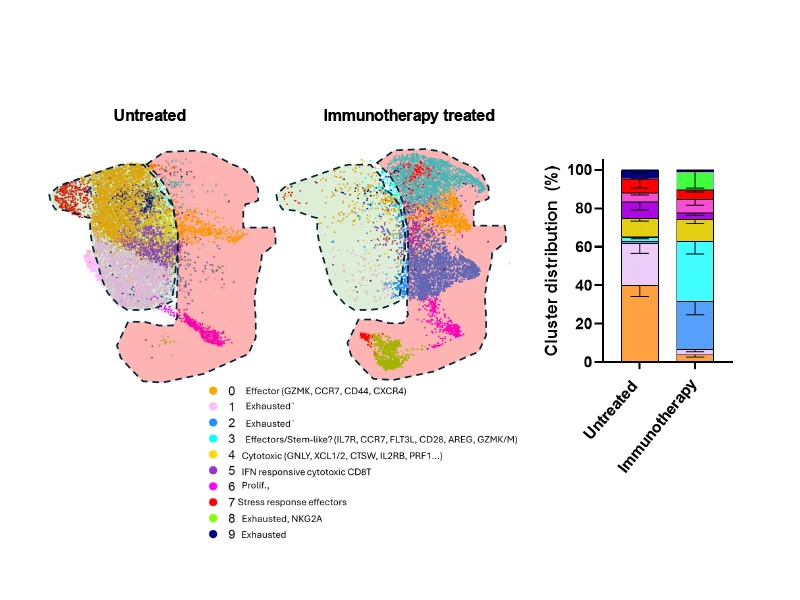

Different distribution of cell types in the microenvironment of those treated with immunotherapy and those not treated. Understanding these changes will help researchers understand why they are working and how to modify regimens to be the most effective.

Building on those findings, the team is launching a phase 2 study to further explore the benefit of chemoimmunotherapy before surgery. The research offers hope both for extending survival and for improving patients’ quality of life. Many patients receive radiation therapy or chemoradiation after surgery to reduce the possibility of recurrence, but this can contribute to serious and lasting side effects, including an inability to speak or swallow food. If future studies confirm that induction chemoimmunotherapy reduces the need for additional treatment after surgery, it could lead to important gains in patient well-being. “Our goal is not only to control the cancer but also to de-escalate some of the therapy patients are getting so they don’t have to live with the significant sequelae of overtreatment,” Dr. Roof says.

Translational Research: Exploring Immune Cells

Meanwhile, the research team is turning to laboratory studies to better understand how head and neck cancer responds to immunotherapy on a cellular level—and to find ways to optimize that response.

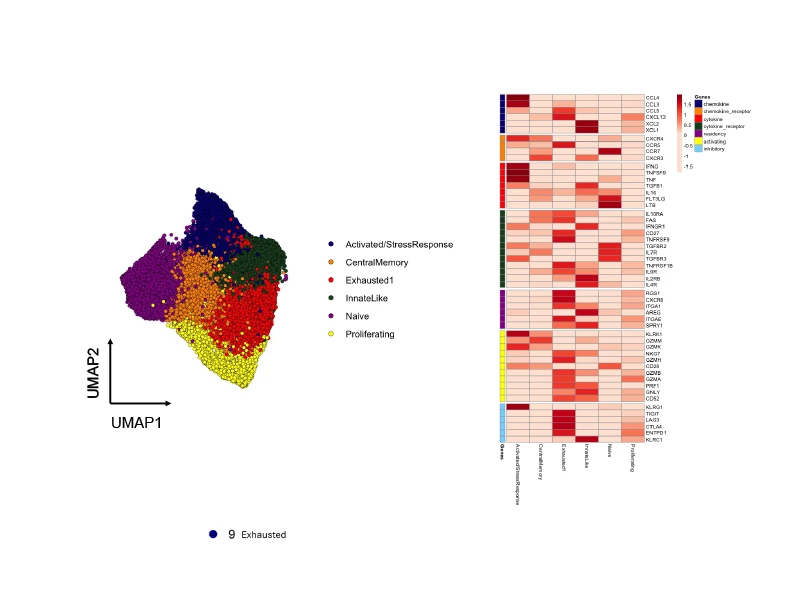

To do so, scientists, including Amir Horowitz, PhD, Assistant Professor of Oncological Sciences, and a member of the Marc and Jennifer Lipschultz Precision Immunology Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine, are working with the clinical teams to compare tissue samples from diagnostic biopsies taken before treatment with samples from tumors surgically removed after immunotherapy treatment. Using innovative, novel technologies, such as single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics, the investigators can identify each of the cell types present in the tumor microenvironment, see how they interact with one another, and explore how cell behavior changes in response to treatment.

Functional subtypes of CD8 T cells present in immunotherapy-treated head and neck tumors and differences in genes relevant for function/therapeutics among those subtypes.

“Using these technologies, we can see which types of immune cells are recruited to the tumor and how they interact both with other immune cells and with cancer cells,” Dr. Roof says.

As they better understand those interactions, the team aims to identify biomarkers that predict a patient’s response to immunotherapy. Such markers could inform decisions about whether to combine immunotherapy with chemotherapy or with other agents to augment the patient’s immune response—courses of action that are likely to differ among patients with active inflammation, those with exhausted immune cells, and those whose tumors exist in immune deserts.

“Do we need to ramp up the whole immune system, for example, or recruit only certain types of immune cells?” Dr. Roof says. “This research is pointing us closer to true precision oncology in head and neck cancer.”

Featured

Scott A. Roof, MD

Director of Clinical Research in the Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery, and Assistant Professor, Otolaryngology

Krzysztof J. Misiukiewicz, MD

Clinical Director of Research in Head and Neck, and the Center for Personalized Cancer Therapeutics, The Tisch Cancer Institute, and Associate Professor, Medicine (Hematology and Medical Oncology) and Assistant Professor, Otolaryngology