For most of us, walking while doing another task, such as scrolling through our phones or talking to a colleague, poses little or no challenge. But among older adults with untreated bilateral hearing loss, dual tasking may lead to falls, according to a new study led by Mount Sinai’s Maura Cosetti, MD, in partnership with colleagues Liraz Arie, PhD, and Anat Lubetzky, PhD, of the NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development’s Department of Physical Therapy.

“Multitasking is second nature to most of us and seems simple, but actually represents a complex process of competing attention,” says Dr. Cosetti, Director of the Ear Institute at New York Eye and Ear Infirmary of Mount Sinai and the Cochlear Implant Program of the Mount Sinai Health System. “Dual-task paradigms allow us to test this in a research setting—and we used it to understand why adults with hearing loss are at high risk for falls.”

People with hearing loss tend to require more effort to listen, she explains, and this may leave less attention available for concurrent tasks. “We wanted to see whether attentional capacity created a higher risk for falls among this population, and our study suggests that it does,” Dr. Cosetti says.

Testing the Impact of Hearing Loss on Mobility and Balance

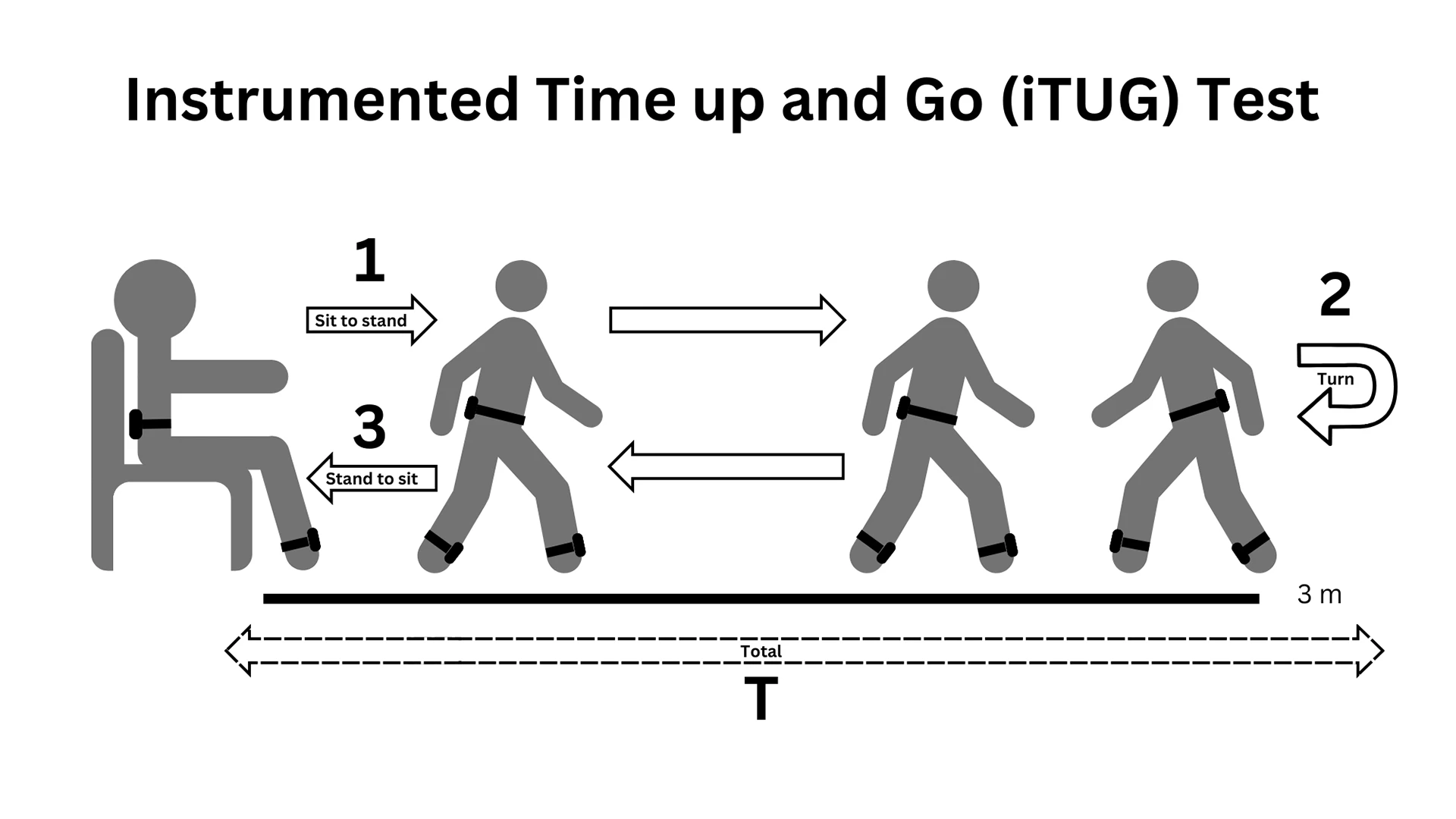

The study recruited 35 individuals ranging in age from 50 to 78 to compare single-task and dual-task performance on the instrumented Timed Up and Go (iTUG) test, a well-validated clinical tool for assessing mobility and balance. The participants were divided into two cohorts—those with mild-to-severe hearing loss (20; mean age 69) and those without hearing loss (15; mean age 63). Each participant was outfitted with wireless sensors, which increased the test’s sensitivity and allowed for analysis of the test’s various subcomponents such as sitting, standing, walking, and turning. For the dual-task portion, patients were asked to subtract serial threes from a randomly identified number as they progressed through each subcomponent of the test.

Participants, wearing wireless sensors, complete a series of subcomponents of the iTUG test: 1) Sit to stand; 2) turn; and 3) stand to sit.

Overall, Dr. Cosetti says everyone was slower when multitasking—specifically, the speed at which they performed the walking and balance tasks was slower when performing concurrent subtraction. Interestingly, patients with hearing loss demonstrated significant differences from those with normal hearing: In the sit-to-stand subcomponent of the test, patients with hearing loss were significantly slower than the non-hearing loss cohort (p<0.03) in both the single- and dual-task configuration. Furthermore, in the final subcomponent of the test, the hearing loss cohort slowed down significantly more in the dual-task configuration compared to the group with normal hearing.

“Essentially, adults with untreated hearing loss have a harder time maintaining their speed on tasks of mobility when they are multitasking, compared with age-matched normal-hearing adults,” says Dr. Cosetti. “This could reflect differences in physical activity between groups, and also suggests that attention may play a role in the high fall risk seen among hearing-impaired adults.”

The study’s findings are particularly noteworthy in that hearing loss was the only differentiator between the two cohorts. This research used a strict study design that ensured both groups were similar on all other measures that could affect their performance (such as vision, musculoskeletal function, neuropathy, etc.). Furthermore, participants were tested to ensure none had dementia—a condition that has been related to hearing loss. The study also filtered out individuals with vestibular dysfunction, which has long been linked to increased risk for falling.

“The fact that we observed differences in balance and mobility between the two cohorts is notable because we made sure both groups were evenly matched across a range of factors such as health and age,” Dr. Cosetti says. “Ultimately, we could not attribute the differences to anything other than hearing loss.”

An iTUG test participant during the sit subcomponent.

The same participant during the turn subcomponent.

Developing Effective Interventions to Reduce Fall Risks

Dr. Cosetti believes the study’s findings not only offer compelling evidence that hearing loss and fall risk are related, but also opportunities for impactful interventions. She recommends conducting a fall risk screening for patients with hearing loss and, more importantly, screening patients with a history of falling for hearing loss. She also believes dual-task training, which has been shown to reduce fall risk in other fields, may offer a viable option for individuals with hearing loss to improve their balance and reduce their risk of falling, as may fall reduction programs. From a research perspective, the next and most important step is to investigate whether treatment of hearing loss (with hearing aids and cochlear implants) has the potential to help reduce fall risk.

“Beyond audibility, hearing loss has wide-ranging effects on health and physical function, and we are just beginning to understand these relationships,” Dr. Cosetti says. “How individuals with hearing loss allocate their attention, especially when walking and multitasking, is one area we are continuing to research. Our goal is to better understand and, ultimately, reduce the risk for falls among adults with hearing loss.”

As Dr. Cosetti and her partners in physical therapy explore this relationship further, they are gaining more insights into how hearing loss contributes to fall risk and the benefits of interventions. She is conducting studies to assess static and dynamic balance, exercise and physical mobility, and the impact of hearing loss treatment relative to physical function.

“Ultimately, our goal is to improve hearing, but we are also interested in understanding how treatment of hearing loss may improve physical function,” she says. “Our hunch is that it has a real opportunity for helping.”

Featured

Maura K. Cosetti, MD

Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery