Inflammation and overproduction of a thick mucus in the nose and sinuses—the hallmarks of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS)—are familiar to many physicians. However, the causes of these symptoms remain elusive.

“We have a greater understanding of the mechanisms implicated in the distal lung that occur in airway diseases than we do of those associated with the upper airway, including the nose and sinus,” says Alison May, PhD, Assistant Professor of Cell, Developmental, and Regenerative Biology, and Otolaryngology, at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “I have made the drivers of CRS the main focus of my lab so my team can help patients not just in the general population, but also among the cystic fibrosis population, where we see an extremely high prevalence of CRS.”

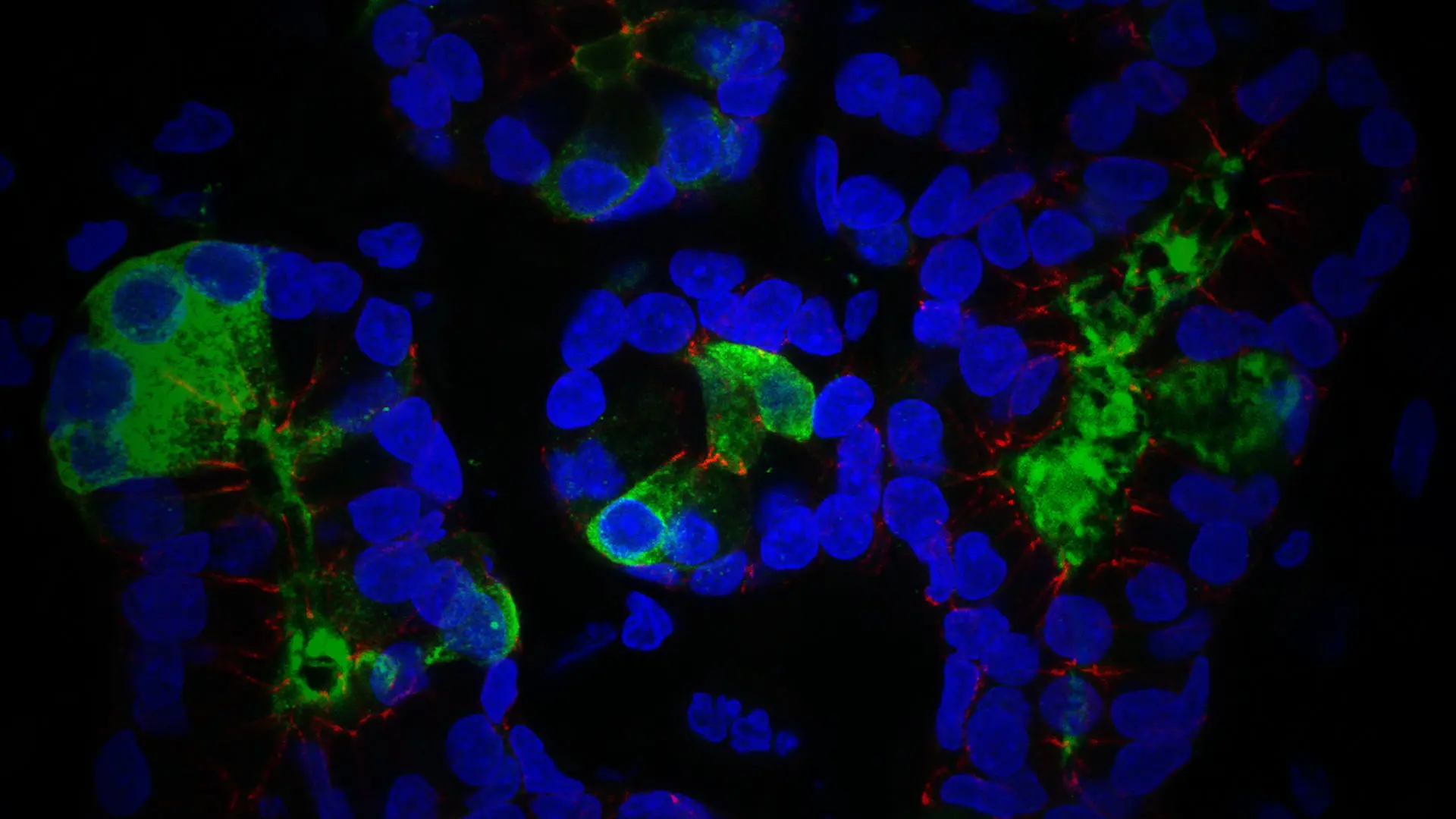

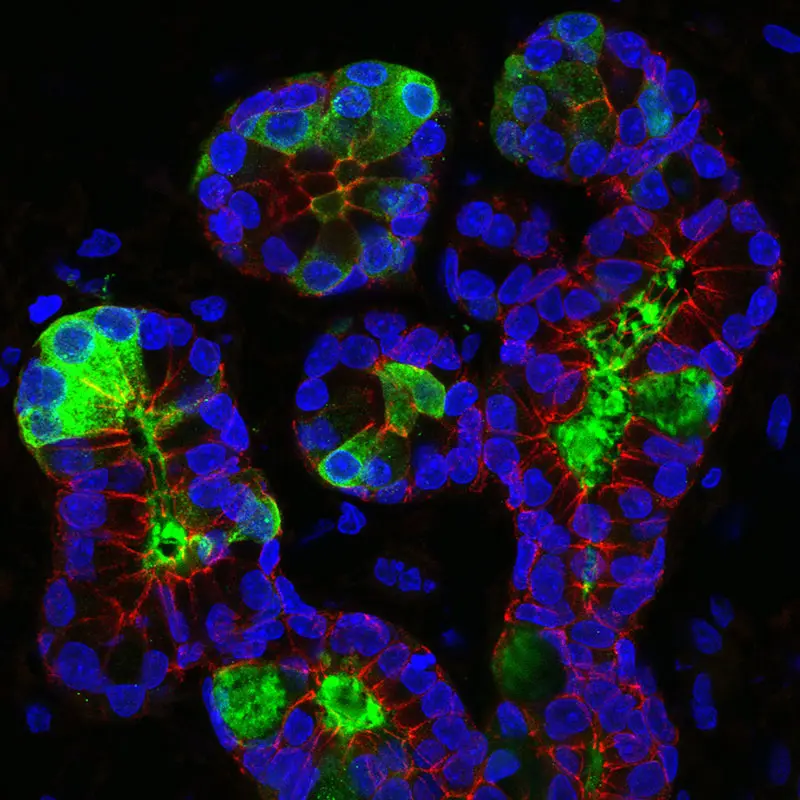

Immunofluorescent image of cells of an airway submucosal gland of the nasal septum. Epithelial cells are outlined in red, mucus secretion shown in green, and cell nuclei shown in blue.

Drawing on her expertise in developmental biology, Dr. May is working to elucidate the causative mechanisms of diseases, specifically those involving changes in the structure and function of the epithelial organs. The changes that are of particular interest to her are those that occur in the submucosal airway glands, resulting in abnormal mucus production, and thus infection and chronic inflammation.

“By studying the development of these tissues, we can understand the mechanisms that give rise to different cell types, as well as their locations and functions,” she explains. “That will provide us with insights not just into drivers of congenital upper airway alterations, but also into changes that may occur in adult sinonasal disease.”

Another approach involves image analysis of biopsies and nasal brushings from adult patients who have undergone surgery to investigate if any epithelial morphological changes have occurred, along with RNA-sequencing techniques to determine if changes in cell populations and gene expression are occurring in different disease conditions.

Examining the Results

In one study, Dr. May analyzed biopsies from adults with CRS and non-CRS controls to characterize the morphology and secretory cell identities of the nasal septum submucosal glands. She observed a significant decrease in gland density in the posterior septum of patients who presented with CRS, both with (23 percent ± 3.09 percent) and without nasal polyps (28 percent ± 6.15 percent) compared to control participants (53 percent ± 1.59 percent, p < 0.0001). Furthermore, she observed a decrease in mucin 5B+ gland mucus among the CRS cohort as well as dilated and cystic ductal structures filled with inspissated mucus. The results of this study were published May 22, 2021, in the International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology.

“Traditionally, it was thought that too many glands were associated with CRS,” Dr. May explains. “But now we know that, at least in this region of the nose, a loss in glandular volume and a notable change in specific glandular cell types occur compared to healthy nasal tissue. This indicates that it might not be a hypersecretory result in that region so much as a hyposecretory one, and we plan to explore these findings further to see if there is a cell type we can target to address this phenomenon.”

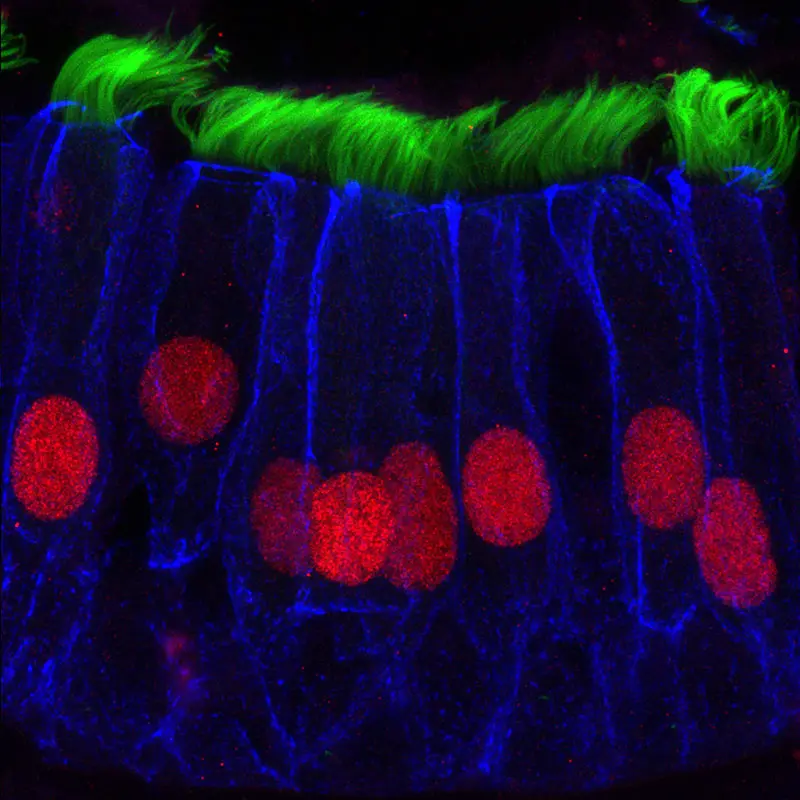

Immunofluorescent image of cells of the airway epithelium of the nasal septum. Epithelial cells are outlined in blue, ciliated cell transcription factor shown in red, and cilia shown in green.

Uncovering the Development of the Nasal Epithelial Cells

Dr. May is also exploring the potential of organ explant cultures—cells grown in vitro using patient tissue samples—to glean further insights on the development of the nasal epithelial cells and how they respond to the introduction of different factors. If successful, her research could accelerate the drug development process or enable precision medicine approaches to treatment. Moreover, it could open the door for bioengineered therapeutic approaches.

“If we can define the factors that are required for creating and directing the different cell populations of the glands, we can then use this knowledge in the application of stem cell-based therapies for organ regeneration and repair,” Dr. May says.

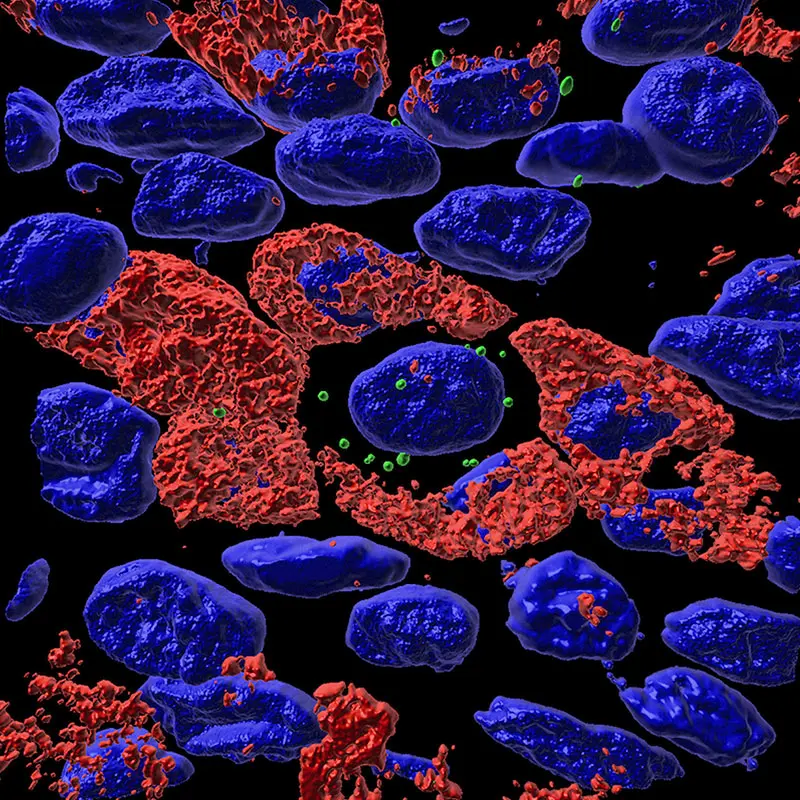

3D image rendering of cells of the airway epithelium. Target RNA highlighted in green, cellular mucus production shown in red, and cell nuclei shown in blue.

Although techniques have been established for growing epithelial cells, Dr. May says there is still considerable work to be done to fully understand the biology behind the development of the submucosal glands and changes that occur in their cell types. Gradually, she is advancing that knowledge through further studies. She is collaborating with the Department of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery to garner more insights on different types of CRS among the general and cystic fibrosis populations through biopsies, computational biology, and both organ and air-liquid interface cultures. She is also interested in studying the factors that account for the significant prevalence—approximately 40 percent—of CRS among World Trade Center first responders. Dr. May believes these efforts will help establish new, more effective therapeutic modalities for patients with CRS.

“It is very important we make great efforts to explore these questions,” Dr. May says. “Not only to advance our understanding of airway biology, but to make critical steps in improving treatment and therapeutics for people living with CRS.”

Featured

Alison May, PhD

Assistant Professor of Cell, Developmental, and Regenerative Biology, and Otolaryngology