A Mount Sinai team in 2025 discovered a circuit in the brain that connects stress with increased glucose and therefore may link stress to type 2 diabetes. In short-term stressful situations, this circuit from the amygdala to the liver naturally provides a burst of energy. However, introducing chronic stress with a fatty diet, researchers observed a disruption in the circuit’s output, specifically, an excess of glucose production in the liver. Long-term elevations in glucose can cause hyperglycemia and increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. The study was published in September 2025 in Nature.

This is the first time researchers have described the connection between the medial amygdala in the brain and liver glucose production. The study, conducted in an animal model, offers the possibility of a new way to target diabetes and shows how important stress is as a driver of diabetes and increased mortality, says corresponding author Sarah Stanley, MBBCh, PhD, Co-Director, Human Islet and Adenovirus Core, Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism Institute, and The Friedman Brain Institute at Mount Sinai.

To date, most studies have focused on how the hypothalamus and brain stem regulate blood glucose. These are regions in the brain that are homeostatic, controlling functions like hunger, thirst, and digestion. Showing that the amygdala, an area traditionally associated with emotion, also controls blood glucose is a major shift in thinking.

“The results of this study not only change how we think about the role of stress in diabetes, but also how we think about the role of the amygdala. Previously, we thought the amygdala only controls our behavioral response to stress—now, we know it controls bodily responses, too. The impact of stress on diabetes is enormous,” says Dr. Stanley, Associate Professor of Medicine (Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease), and Neuroscience, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “But it’s not just diabetes: stress has broader impacts on many other conditions. This means that addressing the social determinants that contribute to stress may improve health, including diabetes.” The study was conducted with investigators from The Friedman Brain Institute, including Paul J. Kenny, PhD, Director of The Friedman Brain Institute, and Nash Family Professor of Neuroscience and Chair of the Nash Family Department of Neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

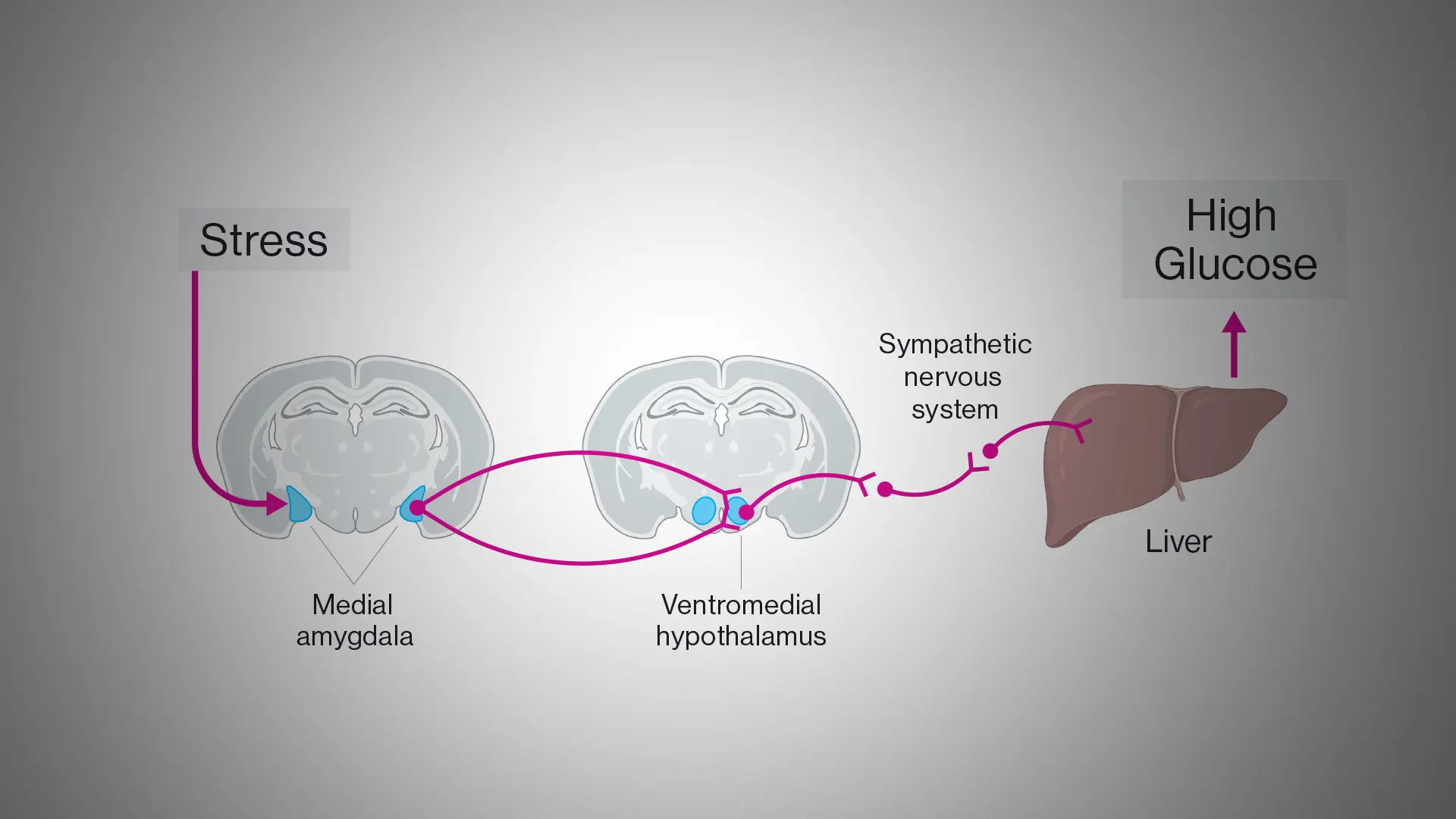

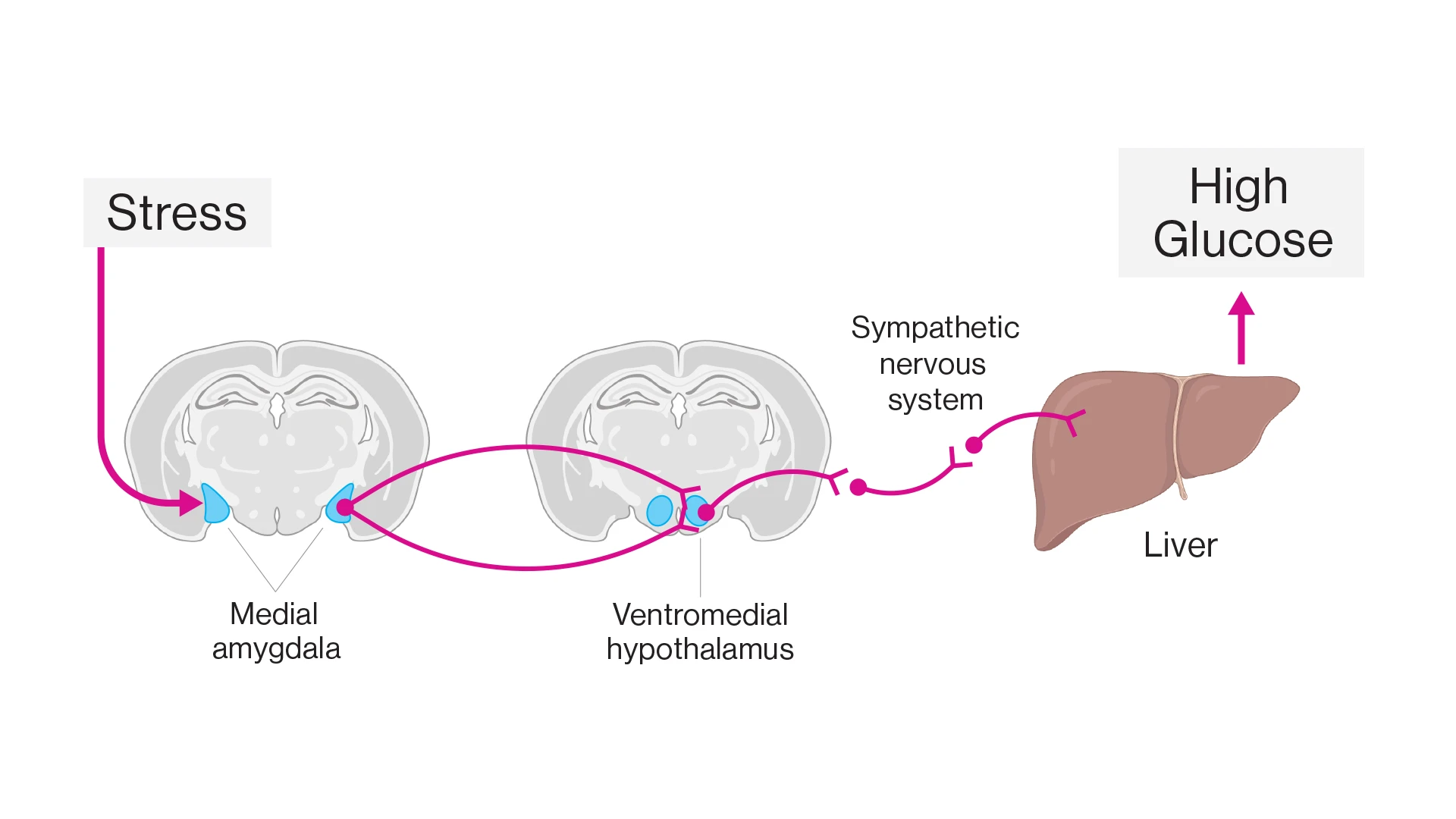

The team identified a circuit linking stress to increased blood glucose. Stress increases activity in neurons of the medial amygdala. These neurons project to and activate neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus that in turn switch on the sympathetic nervous system to the liver. In the liver, neural signals upregulate the production and release of glucose resulting in high glucose in the circulation.

The study showed that exposure to a range of acute stressors rapidly increases circulating blood glucose by 70 percent. At the time of the stress exposure, medial amygdala neuron activity was increased about twofold. Because this change in activity occurred before the change in blood glucose, the investigators hypothesized that the medial amygdala could be driving this increase in glucose. To test this, researchers switched on medial amygdala neurons in unstressed mice, resulting in a 50 percent increase in blood glucose.

To determine the mechanism through which neural activity in the medial amygdala increased blood glucose, the team used viruses to identify and map the neural circuits involved and found that medial amygdala neurons have major connections through the hypothalamus to the liver. When we switched on the amygdala connections to the hypothalamus, the amount of glucose released from the liver almost doubled.

Furthermore, researchers found that a combination of repeated stress and fatty diet altered the circuit between the medial amygdala and liver, resulting in long-term increased glucose, even when the mice were no longer exposed to stress. The research shows that, when exposed to repeated stressors, this circuit became desensitized, resulting in a decreased neural and glucose response to subsequent stress, pushing the mice toward diabetes.

These findings suggest that repeated stress disrupts the medial amygdala-to-hypothalamus-to-liver circuit, increasing liver glucose release.

This study gives clinicians a better understanding of the mechanisms linking stress and glucose control, opening new avenues to develop treatments to help reduce the risk of diabetes and improve glucose control for individuals with diabetes, particularly in individuals with elevated stress levels. By understanding the neural circuits through which stress controls glucose, researchers can identify therapies that help to regulate blood glucose and mitigate the risk of type two diabetes.

Further research is required to study the medial amygdala-to-hypothalamus-to liver circuit in more detail, examine the types of neural cells involved, and observe how short-term and long-term stress changes the circuit structure and gene expression. Additional research would also help understand if taking steps to reduce stress will reverse the disruption in the circuit, lowering the risk of diabetes and returning the circuit to healthy function.

The work was supported by the American Diabetes Association “Pathway to Stop Diabetes” Grant, and in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health and Department of Defense.

Featured

Sarah Stanley, MBBCh, PhD

Associate Professor of Medicine (Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease)

Paul J. Kenny, PhD

Director of The Friedman Brain Institute, and Nash Family Professor of Neuroscience and Chair of the Nash Family Department of Neuroscience