With the publication of two 2024 studies, the Mount Sinai team led by Terry F. Davies, MD, continued to expand understanding of the physiologic mechanisms of Graves’ disease, as well as of thyroid eye disease, which about a third of people with Graves’ disease will develop.

The latest research by Dr. Davies, the Florence and Theodore Baumritter Professor of Medicine (Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, focuses on the thyrotropin receptor (TSHR), the principal regulator of thyrocyte function and growth, and the main autoantigen for Graves’ disease. As Dr. Davies’ prior work has shown, autoantibodies that target the TSHR in patients with Graves’ disease are either stimulating, blocking, or neutral in terms of their cellular activity. A paper published by Dr. Davies and team in December 2024 in Thyroid explored the impact of neutral autoantibodies in a mouse model.

“Our previous work found that neutral autoantibodies are not really neutral at all, but have the capacity to induce thyroid cell stress and trigger a series of events that ultimately result in programmed cell death,” explains Dr. Davies, senior author of the paper. “Our new study learned that just blocking the TSHR binding site will not stop the neutral autoantibodies from doing their damage, because they don’t just bind at that site. We learned from our mouse models that a whole bioreactome consisting of not just the neutrals but other types of autoantibodies, TSHR including stimulating and blocking antibodies, are involved, and that they can bind at multiple sites in the hinge region of the TSHR and elsewhere.”

The implication for scientists investigating therapeutic solutions for Graves’ disease is clear, according to Dr. Davies: The biologic complexities of the disorder may demand a variety of monoclonal antibodies, interfering with different binding sites on the TSH receptor, to pose a truly effective treatment for all patients.

“Our new study learned that just blocking the TSHR binding site will not stop the neutral autoantibodies from doing their damage, because they don’t just bind at that site.”

Terry F. Davies, MD

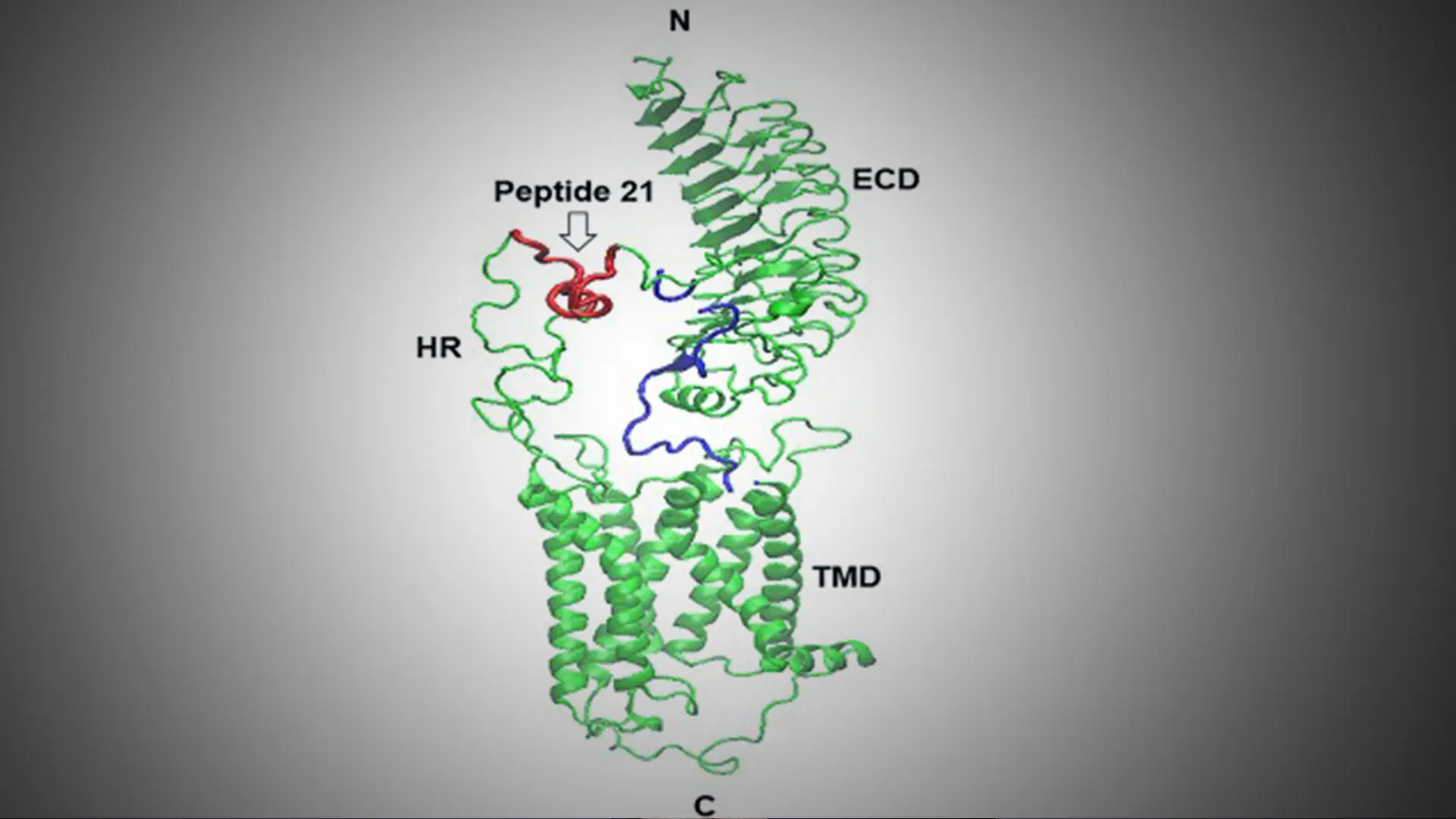

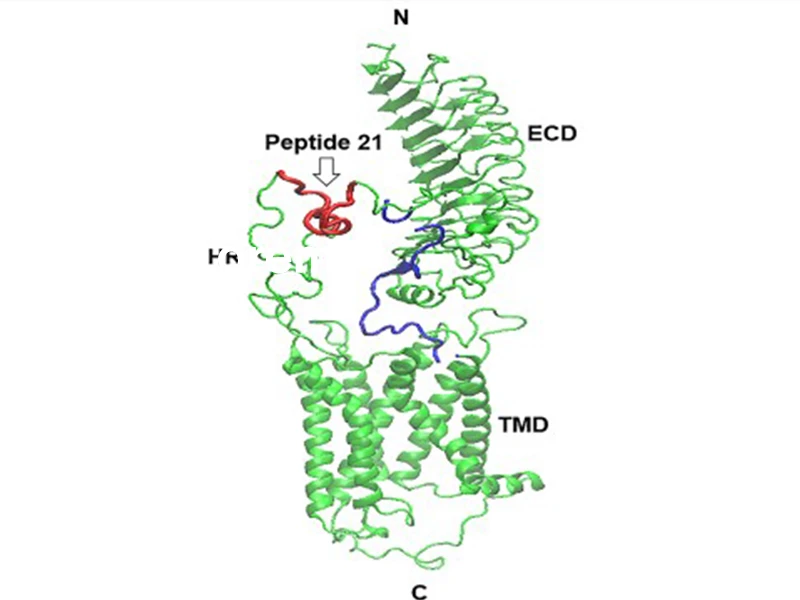

A model of the TSH receptor indicating the immunization peptide 21. HR = hinge region; ECD = extracellular domain; TMD = transmembrane domain; N and C = terminal regions

The same dynamics figure in the second paper by the Davies Lab, analyzing the mechanisms of thyroid eye disease, also known as Graves’ ophthalmopathy. This autoimmune condition affecting the orbits and sometimes the skin is believed to also depend on the expression of the TSHR, the main antigen for Graves’ disease. Researchers found that neutral autoantibodies could be an inflammatory contributor to thyroid eye disease by interacting with the TSHRs on fibroblasts behind the eye, with findings published in October 2024 in the Journal of the Endocrine Society.

In thyroid eye disease, the muscles and fatty tissues become inflamed, causing proptosis, pushing the eyes forward and outward. In 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first drug for treating adults with thyroid eye disease: teprotumumab, an insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor inhibitor (IGF-IR).

The approval of this drug ushered in a new era in the treatment of Graves’ disease, while a host of other advanced therapeutics are now in clinical development. Dr. Davies has spent most of his 45-year career paving the way for these treatments by building his Mount Sinai laboratory into a pre-eminent global site for autoimmune thyroid disease research. “We’re seeing a renaissance in the study of the mechanisms and treatments for autoimmune thyroid diseases,” says Dr. Davies, a past president of the American Thyroid Association who has added more than 400 papers to the field’s body of evidence.

Mount Sinai researchers have provided fodder for future research into thyroid eye disease by uncovering evidence in mice that neutral autoantibodies affect fibroblasts in the eye the same way they do thyroid cells in Graves’ disease—by killing the cells. “Our mechanistic model proposes that these TSHR autoantibodies trigger an inflammatory response in the retro-orbital tissues by activating inflammasomes within the orbital tissue,” notes Dr. Davies. “This results in the release of proinflammatory cytokines that, in turn, perpetuate chronic inflammation, and that could well be contributing to Graves’ eye disease.”

The Davies Lab is already taking the next steps in this rapidly changing field. It is exploring the unique function and signaling of the TSH receptor with the help of a grant from the U.S. Veterans Administration. In August 2024, Dr. Davies received a Senior Clinician Scientist Investigator Award, which extended this grant by four years, to eight years. Experiments show that the TSHR complexes in combination with the IGF-1 receptor and these complexes may offer a valuable therapeutic target in the quest by medical science for innovative new solutions to treat severe thyroid eye disease.

Dr. Davies says, “I’m extremely hopeful that in the next couple of years, two or three new drugs for treating both thyroid overactivity and thyroid eye disease will be approved, allowing for a personalized approach to a disease that can cause severe complications throughout the body if not properly managed.”

Featured

Terry F. Davies, MD

Florence and Theodore Baumritter Professor of Medicine (Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease)