Related Article

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most common disorders of women of reproductive age, affecting up to 20 percent of this population worldwide, depending on the diagnostic criteria applied. It was originally described in the 1930s as a reproductive disorder characterized by irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and hirsutism. Beginning in the 1980s, it was discovered that PCOS was a major metabolic disorder. Women with PCOS were found to have increased prevalence rates of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, important risk factors for cardiovascular disease. However, there have been no definitive studies demonstrating that women with PCOS have increased cardiovascular events, such as myocardial infarction and stroke.

The question of whether PCOS actually confers increased cardiovascular disease risk is of considerable public health importance, given its high prevalence rates. To begin to address this question, a two-day virtual workshop, “Cardiovascular (CV) Risk Across the Lifespan for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome,” was convened in October 2021 by the National Institutes of Health’s National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and Office of Disease Prevention. The objective of this workshop was to identify critical research needs and knowledge gaps regarding cardiovascular disease risk in PCOS. Andrea Dunaif, MD, Chief of the Hilda and J. Lester Gabrilove Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and a global authority on PCOS, was one of the three workshop co-chairs who developed the workshop's scientific agenda.

A unique feature of this workshop was that it brought together preeminent experts in cardiology and epidemiology with leading investigators in PCOS. “Although there is a vast literature demonstrating that reproductive-age women with PCOS have surrogate markers for cardiovascular disease, the only way we’re going to conclusively determine whether PCOS increases cardiovascular disease is through long-term prospective studies that follow affected women to an age when they start to experience cardiovascular events, which is approximately 10 years after menopause, in their 60s and onward,” says Dr. Dunaif. To be successful in this endeavor, it is essential that scientists engaged in cardiovascular science are attracted to the field to address the numerous unanswered questions regarding disease risk.

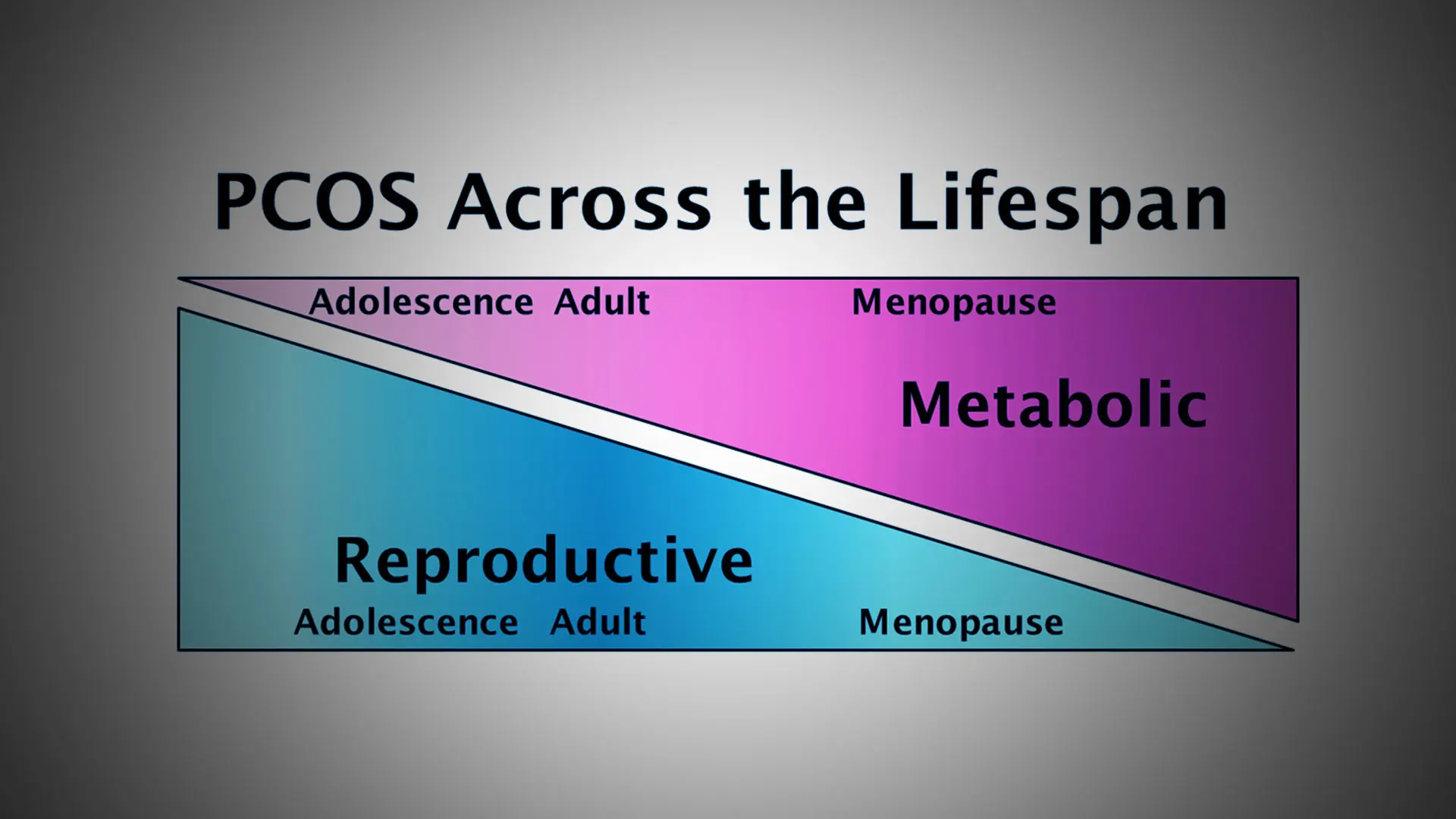

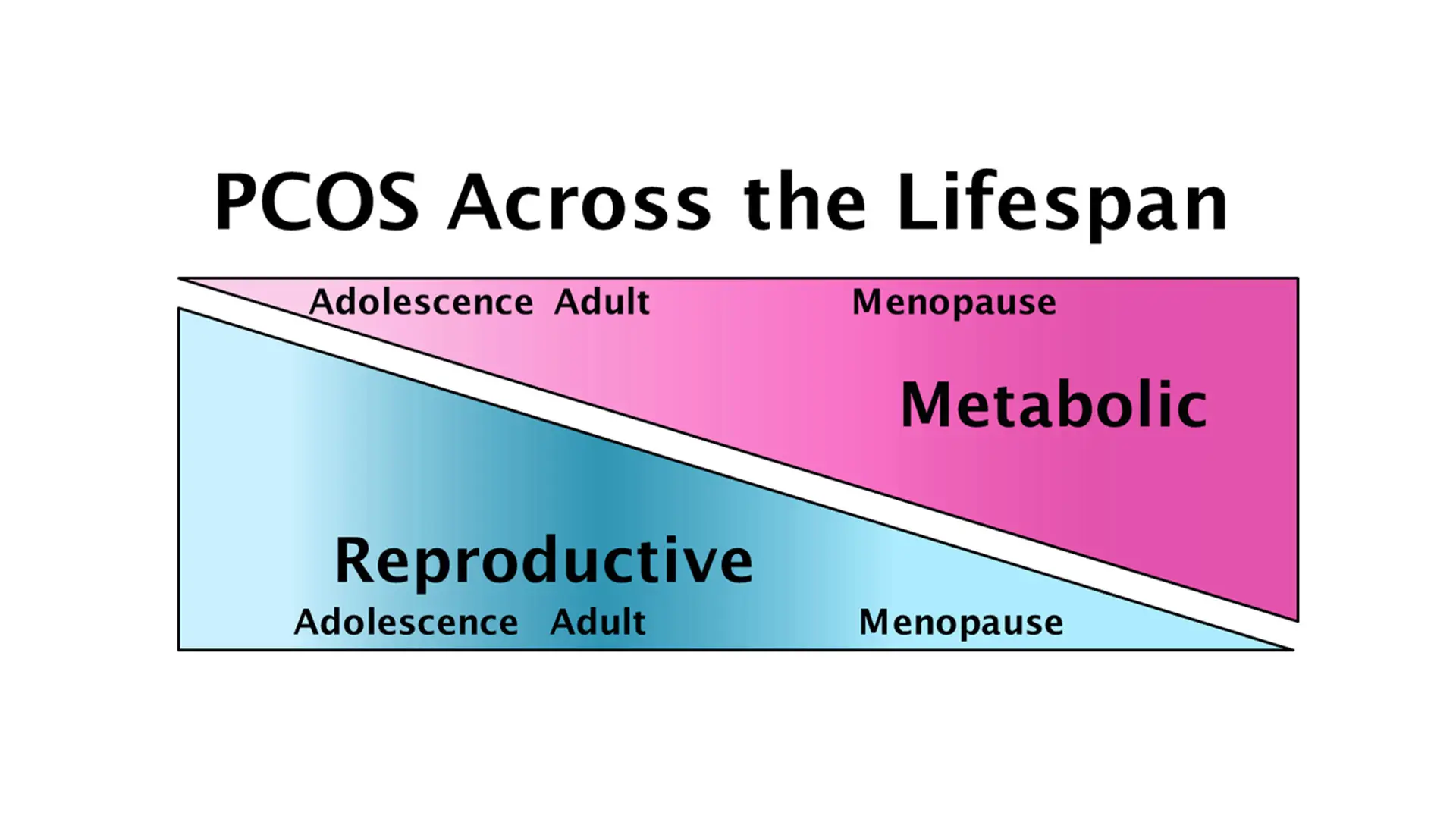

PCOS affects women across the lifespan, with reproductive features that begin in adolescence and resolve with age, and metabolic features that worsen in adulthood and persist after menopause.

One particularly intriguing possibility is whether PCOS itself might confer protection against cardiovascular disease. “Given the substantially increased risk for type 2 diabetes in young women with PCOS, we would expect to see a similar increase in cardiovascular disease risk, since diabetes abolishes the protective effect of premenopausal status on this risk,” notes Dr. Dunaif. However, some studies suggest that there is delayed ovarian aging and menopause in PCOS. Genetic analyses support this observation by finding a relationship between PCOS and genetic variants associated with later age at menopause. “Whether later menopause itself or ‘anti-aging’ actions in other organ systems reduce cardiovascular disease risk in PCOS is a critical unanswered question,” Dr. Dunaif says.

PCOS presents a unique opportunity for cardiometabolic risk reduction. “Since we are able to diagnose PCOS in girls within a couple of years of the start of their menstrual cycle, we could begin modifying risk factors for cardiovascular disease at a very young age,” she says. “These preventive measures could include, for example, carefully monitoring and controlling weight gain, lipid abnormalities, and blood pressure. Currently, there is no attempt to diagnose PCOS at an early age and no counseling about the risk for diabetes, which is really sad because women who are vulnerable to PCOS aren’t getting the care they need.”

Indeed, women with PCOS are highly dissatisfied with the health care they receive. It usually takes more than two years and visits to three or more health care providers before PCOS is diagnosed. “There is clearly a tremendous need for health care provider education regarding the diagnosis, multisystem manifestations, and management of PCOS. A major impediment to educational initiatives is the name ‘PCOS’ itself. It is a misnomer in that there are no cysts in the ovary. Further, the name focuses on the ovary when PCOS is actually much more than a reproductive disorder,” says Dr. Dunaif.

The expert panel from the last major NIH meeting on PCOS, the Evidence-Based Methodology Workshop, held in 2012, recommended that the name be changed to one that reflects the fact that it is a complex endocrine and metabolic disorder affecting women across the lifespan. Efforts to change the name to one that meets the requirements of all stakeholders, including patients, are ongoing.

Featured Faculty and Division Leadership

Andrea Dunaif, MD

Lillian and Henry M. Stratton Professor of Molecular Medicine; Chief of the Hilda and J. Lester Gabrilove Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Bone Disease