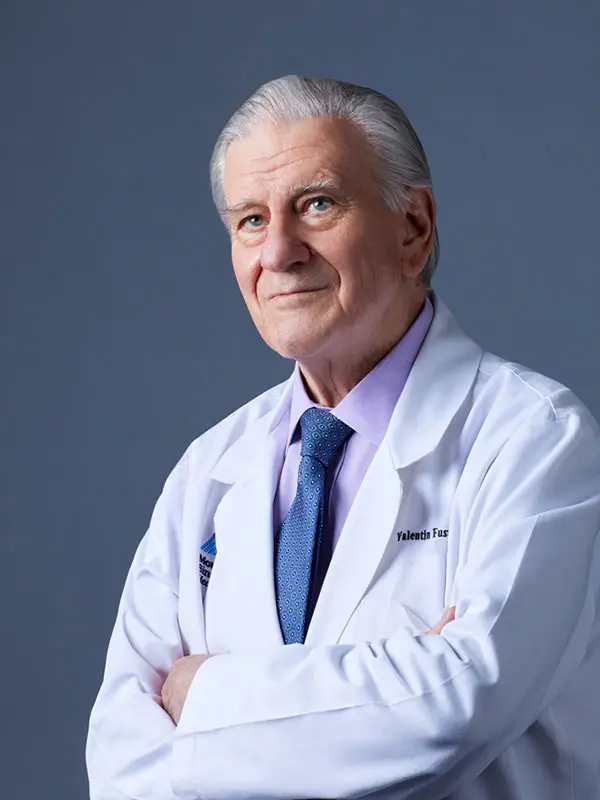

In the earliest days of COVID-19, Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD, Director of Mount Sinai Heart and Physician-in-Chief of The Mount Sinai Hospital, noticed that a large number of admitted patients had small blood clots in their legs. After learning from colleagues in China of similar cases that had triggered myocardial infarctions, strokes, and pulmonary embolisms, he took decisive action.

“We became one of the first medical centers in the world to treat all COVID-19 patients with anticoagulant medications,” says Dr. Fuster, a pioneer in the study of atherothrombotic disease. “It was a decision we believe saved many lives.”

That early insight paved the way for groundbreaking research by Mount Sinai scientists into the role of anticoagulation in the management of COVID-19 patients. The work included a study published in August 2020 in the Journal of American College of Cardiology that showed a 50 percent higher chance of survival with anticoagulation therapy than in patients given no anticoagulant. While observational, that study paved the way for the design and launch in November of the global FREEDOM COVID-19 Anticoagulation Trial with an eye toward determining the most effective dosage and regimen of anticoagulation to improve the survival of hospitalized patients.

Additional research delved into a related—and controversial—question: whether the sickest patients on respirators were experiencing classic acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or an entirely different phenomenon. Among the findings to emerge was that blood clots in the lungs and dilation of the pulmonary vessels may both play major roles in the most severe cases triggered by SARS-CoV-2, and that treatment might follow the model for pulmonary embolism: anticoagulation drugs for milder cases and thrombolysis, or clot dissolution, along with continued anticoagulation for the most seriously ill patients.

"We became one of the first medical centers in the world to treat all COVID-19 patients with anticoagulant medications. It was a decision we believe saved many lives."

Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD

“It became clear to us that the new virus wreaks havoc on the pulmonary vasculature in a variety of ways, some of them quite surprising,” says Hooman Poor, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine (Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine) at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, who has helped lead the clinical and research effort. “We learned, for example, that the reason many patients on respirators weren’t getting enough oxygen was because capillaries in their lungs were abnormally dilated, allowing large volumes of blood to pass through quickly without picking up sufficient oxygen. At the same time, our studies showed that extensive blood clots in the lungs—a known consequence of coronavirus—were possibly detouring blood to the already dilated vessels. This phenomenon could account for the very low oxygen levels seen in COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure, as well as help explain why the disease behaves differently than classic acute respiratory distress syndrome.”

As so often happens in scientific discovery, the way those findings came to light was largely through serendipity. Alexandra Reynolds, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery, and Neurology, at Icahn Mount Sinai, began assessing the cerebral blood flow in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients with altered mental status in search of abnormalities consistent with stroke. For this task she used a robotic transcranial Doppler to perform a “bubble study,” a non-invasive ultrasound technique that provides for injecting saline containing microbubbles into the patient’s vein, then tracking them through the Doppler. Normally, these bubbles would travel to the right side of the heart, enter the blood vessels of the lungs, and get filtered out of the bloodstream by the pulmonary capillaries. Dr. Reynolds observed, however, that many of these microbubbles were somehow finding their way into the brain.

"It became clear to us that the new virus wreaks havoc on the pulmonary vasculature in a variety of ways, some of them quite surprising."

Hooman Poor, MD

She described her findings to an astounded Dr. Poor, who realized they could possibly be the missing link to the mystery of why COVID-19 patients were suffering from severe hypoxemia. “All the signs suggested to me pulmonary vasodilation,” he recalls, a suspicion that was confirmed through a follow-up study with Dr. Reynolds of 18 ventilated patients of whom 15 had detectable microbubbles. “Not only did these findings indicate the presence of abnormally dilated pulmonary blood vessels, but the number of microbubbles correlated with the severity of the hypoxemia seen in many patients with COVID-19 pneumonia,” he elaborates.

After months of clinical observation and pathology lab work at Mount Sinai, a treatment protocol took shape. Researchers reasoned that full systemic anticoagulation to mitigate disease progression in the early stages of SARS-CoV-2, and thrombolysis with agents like tPA for more advanced cases, could be a prudent approach.

The FREEDOM COVID-19 Anticoagulation Trial is expected to write the next chapter. That study, involving more than 70 sites in nine countries, is evaluating the safety and effectiveness of three different anticoagulation regimens: prophylactic enoxaparin, full-dose enoxaparin, and apixaban. “Even with the rollout of vaccines,” stresses Dr. Fuster, Principal Investigator of the FREEDOM Trial, “there’s an urgent need to determine how to best care for the next wave of hundreds of thousands of COVID-19 patients globally.”

Featured

Valentin Fuster, MD, PhD

President of Mount Sinai Fuster Heart Hospital, and Physician-in-Chief of The Mount Sinai Hospital