No work took on greater urgency in the heat of the pandemic than the hunt by researchers from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Division of Infectious Diseases for antibodies that could protect against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. That effort coalesced around the identification of subclasses of those antibodies present in the milk of nursing mothers and in the plasma of COVID-19 patients that might be capable of blocking the spread of infection.

Rebecca Powell, PhD, Assistant Professor of Medicine (Infectious Diseases) at Icahn Mount Sinai, is part of the research team that collectively turned on a dime once the pandemic struck. Describing herself as a human milk immunologist, Dr. Powell began scouring the city in the early days of the pandemic for milk samples from COVID-19-recovered donors to help answer several critical questions, including whether this milk could confer a level of passive protection against viral infection through the mother’s antibodies.

“The field was riddled at the time by misinformation regarding potential dangers to infants being breastfed by COVID-19-infected mothers,” recalls Dr. Powell, whose interest in human milk immunology surged when she became a mother herself. “We now know that milk from nursing mothers who have been infected is 100 percent safe for babies, and that antibodies in the milk provide a protective coating to the baby’s mucous membranes, though it needs constant replenishment.” That protection, she adds, is one of the only ways to safeguard this vulnerable population until a pediatric COVID-19 vaccine is available.

In the first of two major studies published over the past year, Dr. Powell and her team took milk samples from 15 recovering COVID-19 patients to test for antibodies binding to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They found that the dominant form of antibody in milk after infection was the secretory form of immunoglobulin A (sIgA). “What makes sIgA particularly potent,” explains Dr. Powell, “is that it’s wrapped in an additional secretory component, a protein that is highly stable and resistant to enzymatic degradation and, therefore, very protective of the antibody.”

"Imagine if you could administer antibodies through a nebulizer directly to the respiratory tract. That has implications well beyond COVID-19 and could push the field in a direction it’s never been before."

Rebecca Powell, PhD

The protective capacity and stability of sIgA for breastfed infants is pivotal to the next phase of Dr. Powell’s work: potentially using the antibody as a COVID-19 therapeutic for a much larger population.

“sIgA is stable not only in milk and the infant’s mouth, but in all the mucosa, including the nose, gastrointestinal tract, and upper airway and lungs, all of which are sites where the virus is most likely to infect,” she notes. “That’s why mucosal immunity against COVID—to which mother’s milk contributes—is so crucial, and why we’re exploring the possibility of extracting sIgA from the milk of mothers previously infected and using it therapeutically. Imagine if you could administer antibodies through a nebulizer directly to the respiratory tract. That has implications well beyond COVID-19 and could push the field in a direction it’s never been before.”

While Dr. Powell was investigating antibodies in human milk, two other Mount Sinai infectious disease researchers—Susan Zolla-Pazner, PhD, and Catarina Hioe, PhD, Professors of Medicine (Infectious Diseases), and Microbiology—were exploring their presence of antibodies in plasma and their ability to block infection. Working with the Department of Microbiology right after the pandemic struck, they developed within 10 days an assay able to measure the different immunoglobulin subclasses in the plasma of acutely infected and convalescent individuals—primarily IgA, IgM, and IgG—and then determine which had neutralizing activities against SARS-CoV-2.

“We knew this information would not only help us understand how the human body was responding to the viral infection, but also allow us to start building vaccines that could induce different types of antibodies needed for protection in humans,” explains Dr. Zolla-Pazner.

The awareness that antibodies are also found abundantly in saliva has opened another promising investigative avenue for infectious disease researchers. In a study recently published online in medRxiv, Dr. Hioe, the senior author, and her team reported that compared to natural infection, COVID-19 vaccines induced a greater array of IgG subtypes with virus-neutralizing activity in both saliva and plasma. “Knowing what isotypes and levels of isotypes are present in saliva and plasma,” emphasizes Dr. Hioe, “will take us an important step closer to knowing which antibodies offer the best protective shield against viruses like SARS-CoV-2.”

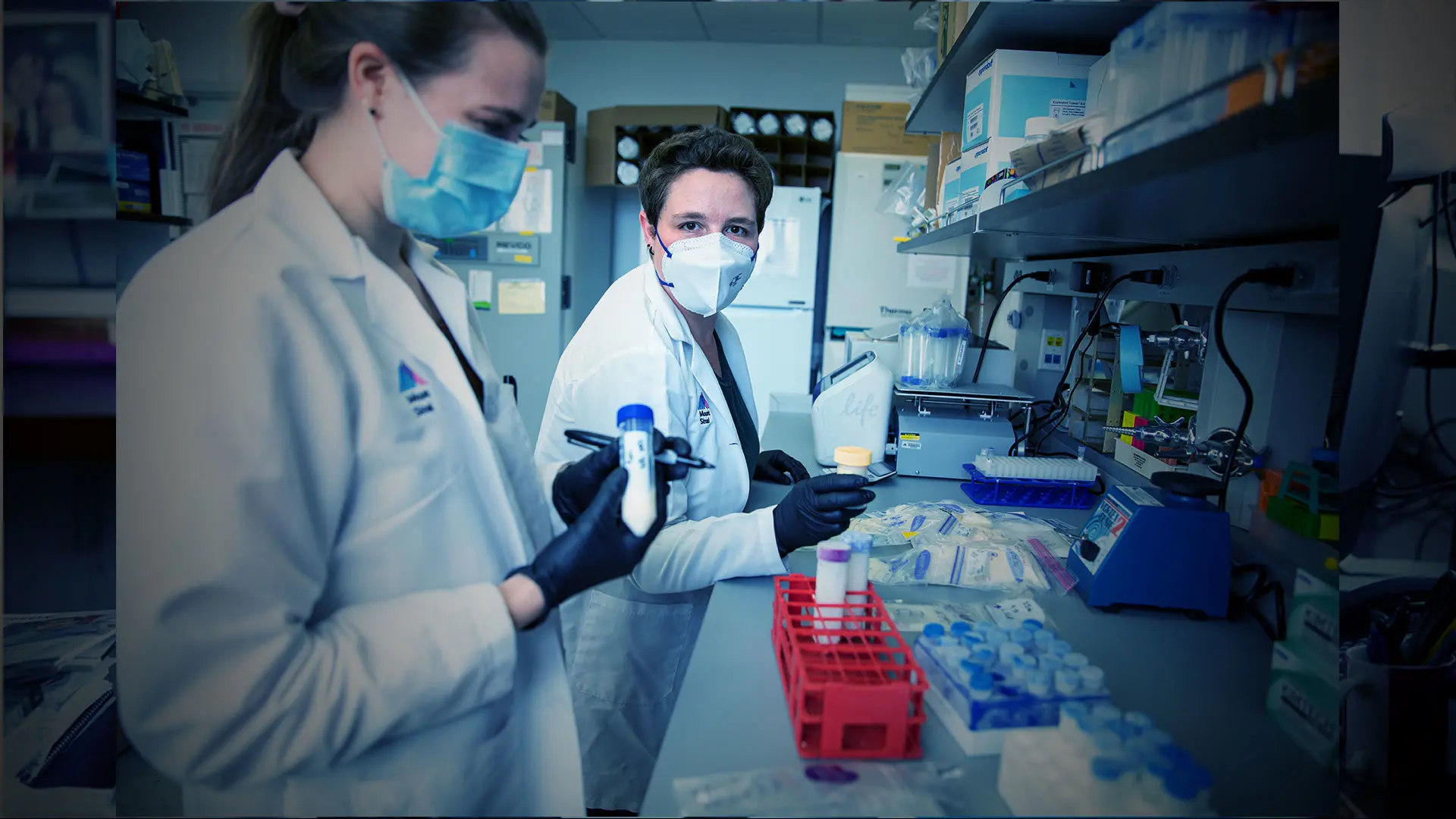

Catarina Hioe, PhD, left, and Susan Zolla-Pazner, PhD, are researching the presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in plasma and saliva.

Featured

Charles A. Powell, MD, MBA

Chief of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine; Director, Mount Sinai Respiratory Institute