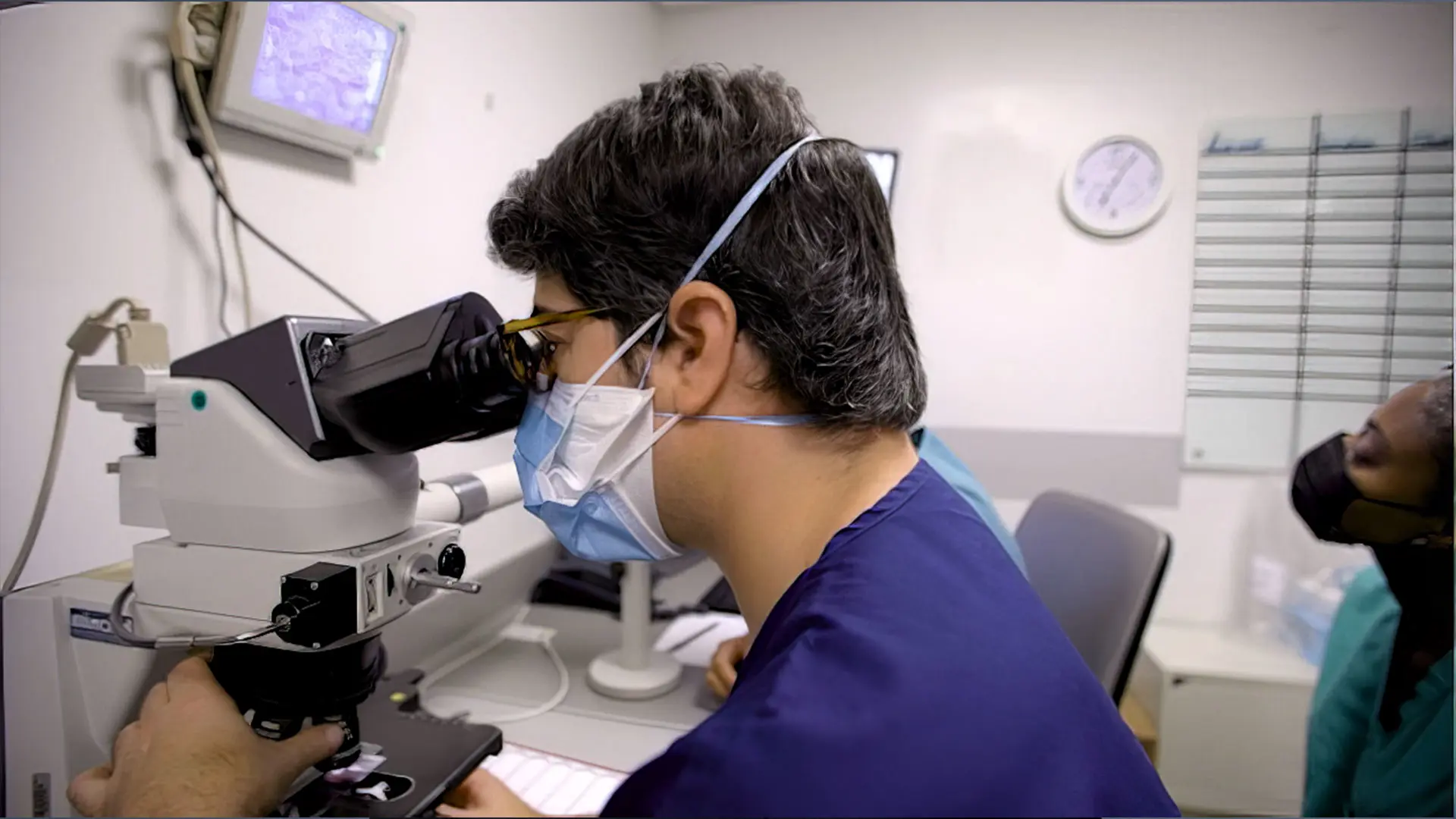

Jonathan Ungar, MD, uses the Vectra® system to deliver 360-degree full-body patient imaging at the Waldman Melanoma and Skin Cancer Center.

Each year, the doctors and researchers at the Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Melanoma and Skin Cancer Center at Mount Sinai diagnose and treat thousands of patients with all types of skin cancer, including melanoma. The goal, says Jonathan Ungar, MD, Assistant Professor of Dermatology, and Medical Director of the Center, is not just to achieve the best possible outcomes for these patients, but also gain insights that result in earlier diagnosis and more effective treatment overall.

“We are able to do this at a level that is relatively unmatched based in part on the volume of patients we see and the state-of-the-art imaging and analysis technologies we have invested in to identify and monitor lesions among patients,” says Dr. Ungar. “I think we are using these technologies in increasingly innovative ways that other centers may not yet be using them.”

The Waldman Center was one of the first centers to invest in the Vectra® WB180 system, which can deliver 360-degree full-body patient imaging in minutes. It was also among the first to adopt diagnostic technologies that enable “bladeless” biopsies, such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) and optical coherence tomography (OCT). That early adoption has enabled Dr. Ungar and his colleagues to identify ways to use them together to significantly enhance detection, assessment, and monitoring of lesions among patients.

“Instead of conducting noninvasive biopsies of each lesion of concern using RCM, which is a time-consuming process, we are using Vectra imaging to zero in on lesions that have changed in a way that is potentially meaningful and then test them,” Dr. Ungar says. “That is more practical for us and for our patients because we are able to eliminate unnecessary biopsies and focus our attention on high-yield lesions.”

Jesse Miller Lewin, MD, FACMS, is refining the Waldman Center’s approach to treating early-stage melanoma, specifically using Mohs micrographic surgery

MART-1 Immunostaining With Mohs Surgery

As Dr. Ungar leads the effort to enhance identification of lesions of concern, Jesse Miller Lewin, MD, FACMS, is refining the Waldman Center’s approach to treating early-stage melanoma, specifically using Mohs micrographic surgery. During Mohs surgery, tissue is resected in stages and microscopically analyzed to confirm that the cancerous tissue has been completely removed. Using melanoma antigen recognized by T cell (MART-1) immunohistochemical staining, Dr. Lewin is able to visualize the margins of the melanoma during surgery, resulting in more effective treatment and better tissue conservation among patients.

“We know that patients with melanomas above the neck were more likely to have an upstaged lesion or an incomplete resection,” says Dr. Lewin, Vice Chair of Surgical Operations, System Chief of the Division of Dermatologic and Cosmetic Surgery, and Program Director for the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship Program. “This suggests surgeons may remove narrow margins on cosmetically sensitive areas, which can lead to inadequate sampling for diagnosis, or incomplete removal. By performing Mohs with MART-1 immunostaining, we are able to remove the melanoma, analyze it, and confirm it is fully removed before we repair the wound. That results in a better cosmetic outcome for our patients while reducing the risk for incomplete resection and recurrence.”

Immunotherapy Research

The spirit of innovation also guides immunotherapy research being conducted by Nicholas Gulati, MD, PhD, at the Waldman Center. He is leading a clinical trial to assess the potential of administering a topical immunotherapeutic agent— diphencyprone (DPCP)—to enhance the epicacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors, the standard of care for treatment of skin cancers. To date, one patient has completed treatment, and Dr. Gulati says the clinical response was encouraging. But it is the collection of skin biopsies and blood samples that is being conducted over the course of the study that he believes could be transformative in immunotherapeutic approaches to skin cancer.

“Immunotherapy is increasingly becoming a pillar of cancer treatment,” says Dr. Gulati, Assistant Professor of Dermatology, Director of the Early Detection of Skin Cancer Clinic, and Director of the Oncodermatology Clinic. “But there are considerable gaps in our understanding of its efficacy. By looking at these biopsies and blood samples, we can gain more insights on how the immune system fights cancer, thus filling in those gaps and making this relatively new arena of cancer treatment more effective.”

Before and after photos from the first patient to complete the clinical trial. The bumps on the patient’s scalp represent skin metastases.

Immunotherapy in Skin Cancers Including Melanoma Shows Promising Results

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, which use the patient’s own immune system to attack cancer cells, are effective treatments for patients with advanced melanoma and other skin cancers, but can lead to serious side effects. “In an ongoing clinical trial for patients with melanoma and other skin cancers that have advanced disease and skin metastasis, we are combining immune checkpoint inhibitors (administered intravenously) with a topical ointment called DPCP which when applied to the skin lead to a notable immune response, but without having internal side effects as with immune checkpoint inhibitors. We have been able to show that adding this topical therapy leads to quicker and better disappearance of the skin cancers than immune checkpoint inhibitors alone,” says Dr. Gulati.

At the same time, Dr. Gulati and his team are doing studies in the laboratory on skin cancer tissue and blood samples from these patients to better understand how exactly the immune system can be used against melanoma and other skin cancers.

“We are also studying rashes caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors in the laboratory, as the skin is the most common organ to have side effects from these therapies. Many different skin rashes are caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors, including eczema, psoriasis, lichen planus, bullous pemphigoid, alopecia areata, and prurigo nodules. These skin toxicities are usually treated by oral steroids such as prednisone, which have many side effects and may interfere with the ability of immune checkpoint inhibitors to effectively treat melanoma and other cancers,” says Dr. Gulati. “A better understanding of these skin toxicities will lead to targeted treatments that are safer and more effective than what we currently can offer patients.”

Patrick Brunner, MD, provides excellent patient care and focuses on conducting research in targeted treatments for cutaneous lymphomas.

JAK Inhibitor to Treat Lymphoma

Patrick M. Brunner, MD, is also looking at the efficacy of targeted treatments for skin cancers. In a first-of-its-kind clinical trial, he is assessing the potential of using a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor—an immune modulating agent that is used to treat chronic inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis—to treat cutaneous lymphomas. Over the course of the trial, a total of 20 patients with cutaneous lymphomas will receive a JAK3 inhibitor for six months, followed by an observational period to see how long the skin lesions will remain in remission.

It is very difficult to get rid of these lymphoma cells completely,” says Dr. Brunner, Associate Professor of Dermatology, and Director of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Clinic. “The goal is to effectively put these cells to sleep so that they become inactive over the long term. If the trial is successful, then we will expand the study further.”

New Approaches to Skin Cancer Research

But what if it were possible to learn the language of cells that promotes malignant tumor growth? That is what Andrew L. Ji, MD, Assistant Professor of Dermatology, is working to understand. He is exploring cell communication in the context of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), specifically among individuals who have undergone organ transplantation.

Dr. Ji has discovered an invasive cSCC subpopulation that communicates with, or manipulates, nonmalignant cells to promote tumor growth. Using innovative single-cell and spatial technologies, he is profiling tumors from organ transplant recipients to better understand how this communication occurs. “The goal is to generate a large cohort of patient tissue profiles that serve as a blueprint for all the communication pathways that are happening,” Dr. Ji says. “Once we complete our analysis of this cohort, we can start testing the most promising pathways to see if we can block that communication and thus block the aggressive behavior of these tumors.”

Jonas Adalsteinsson, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Dermatology, conducts research on how environmental factors affect skin cancer risk. “For example, certain medications such as hydrochlorothiazide can accentuate skin cancer risk,” says Dr. Adalsteinsson.

As the Waldman Center’s researchers continue to advance diagnosis and treatment, they are planning for what comes next. Dr. Ungar envisions the development of new technologies, such as artificial intelligence tools, that can mine new insights from the vast data the Center is collecting.

“The more research we do, the more patients we treat, the more knowledge we gain—all of that will lead to earlier detection and new interventions that could reverse tumor growth or prevent recurrence,” Dr. Ungar says. “That means we will be able to help more patients with personal or familial history of melanoma and other skin cancers in ways that change their lives.”