A study led by Mount Sinai researchers is the first to demonstrate how the heart and brain communicate with each other through the immune system to promote sleep and recovery after a major cardiovascular event. The novel findings, published in October 2024 in Nature, emphasize the importance of increased sleep after a heart attack, and suggest that sufficient sleep should be a focus of clinical management after a heart attack, including in intensive care units and in cardiac rehabilitation, says Filip K. Swirski, PhD, Director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Mount Sinai, and an author of the study.

The study found that in humans and mice, monocytes are actively recruited to the brain after myocardial infarction (MI) to augment sleep, which suppresses sympathetic outflow to the heart, limiting inflammation and promoting healing. After MI, microglia rapidly recruit circulating monocytes to the brain’s thalamic lateral posterior nucleus (LPN), where they are reprogrammed to generate tumor necrosis factor (TNF). In the thalamic LPN, monocytic TNF engages neurons to increase slow-wave sleep pressure and abundance. Increased sleep after an MI is a beneficial response that limits stress on the heart and promotes healing. Disrupting sleep after MI or manipulation of TNF signaling in the LPN increases cardiac sympathetic signaling, worsens cardiac function, and elevates cardioinflammation by signaling through cardiac macrophage adrenergic receptors.

“This study is the first to demonstrate that the heart regulates sleep during cardiovascular injury by using the immune system to signal to the brain. Our data show that after a myocardial infarction, the brain undergoes profound changes that augment sleep, and that in the weeks following a myocardial infarction, sleep abundance and drive is increased,” says senior author Cameron McAlpine, PhD, Assistant Professor of Medicine (Cardiology), and Neuroscience at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The research team first used mouse models to discover this phenomenon. They induced heart attacks in half of the mice, performed high-resolution imaging and cell analysis, and used implantable wireless electroencephalogram devices to record electrical signals from their brains and analyze sleep patterns. After the heart attack, they found a threefold increase in slow-wave sleep, a deep stage of sleep characterized by slow brain waves and reduced muscle activity. This increase in sleep occurred quickly after the heart attack and lasted one week.

When the researchers studied the brains of the mice with heart attacks, they found that monocytes were recruited from the blood to the brain and used TNF to activate neurons in the thalamus, which caused the increase in sleep. This happened within hours after the cardiac event, and none of this occurred in the mice that did not have heart attacks. The researchers then used advanced approaches to manipulate neuron TNF signaling in the thalamus and uncovered that the sleeping brain uses the nervous system to send signals back to the heart to reduce heart stress, promote healing, and decrease heart inflammation after a heart attack.

“This study is the first to demonstrate that the heart regulates sleep during cardiovascular injury by using the immune system to signal to the brain. ”

Cameron McAlpine, PhD

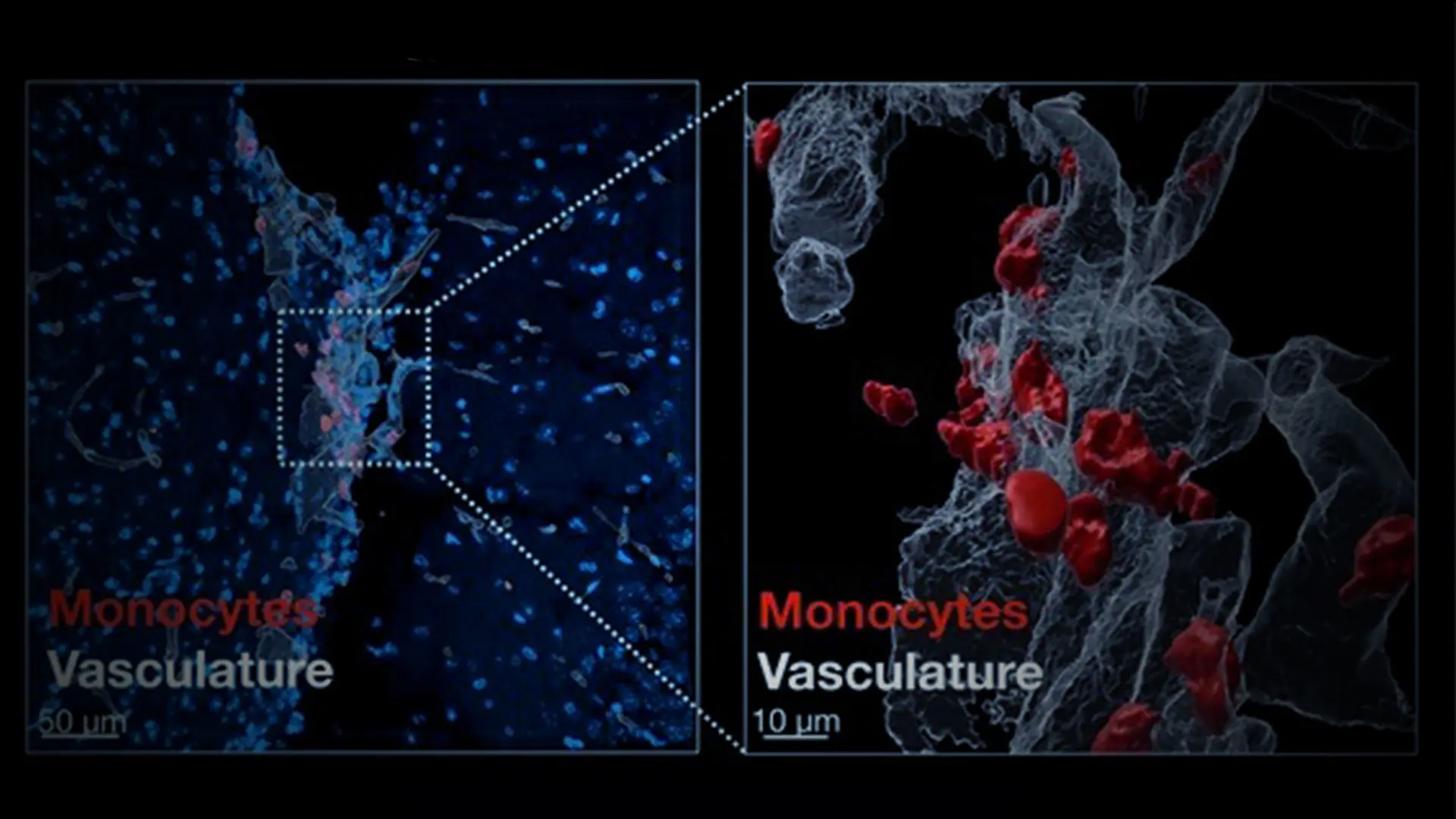

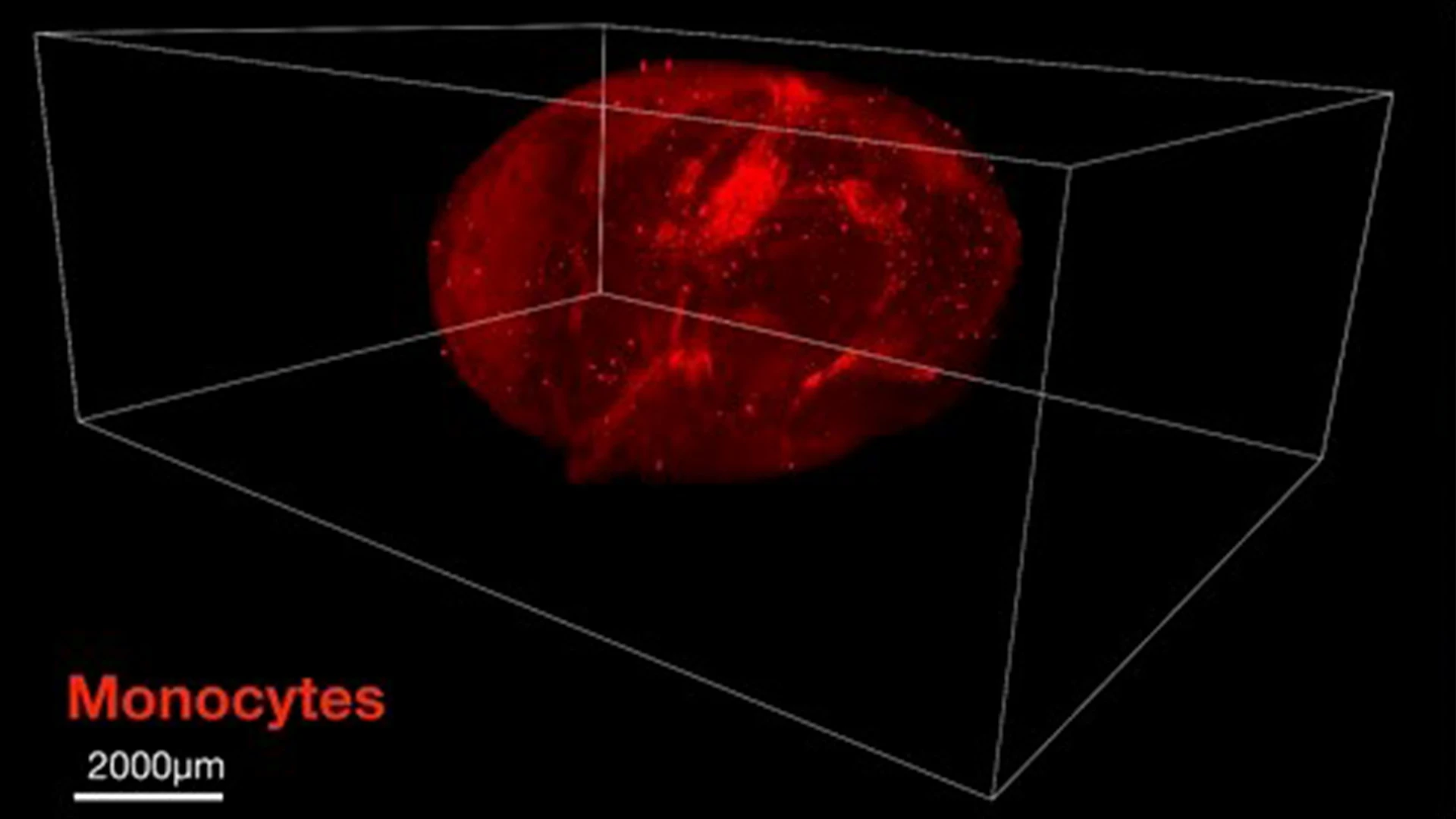

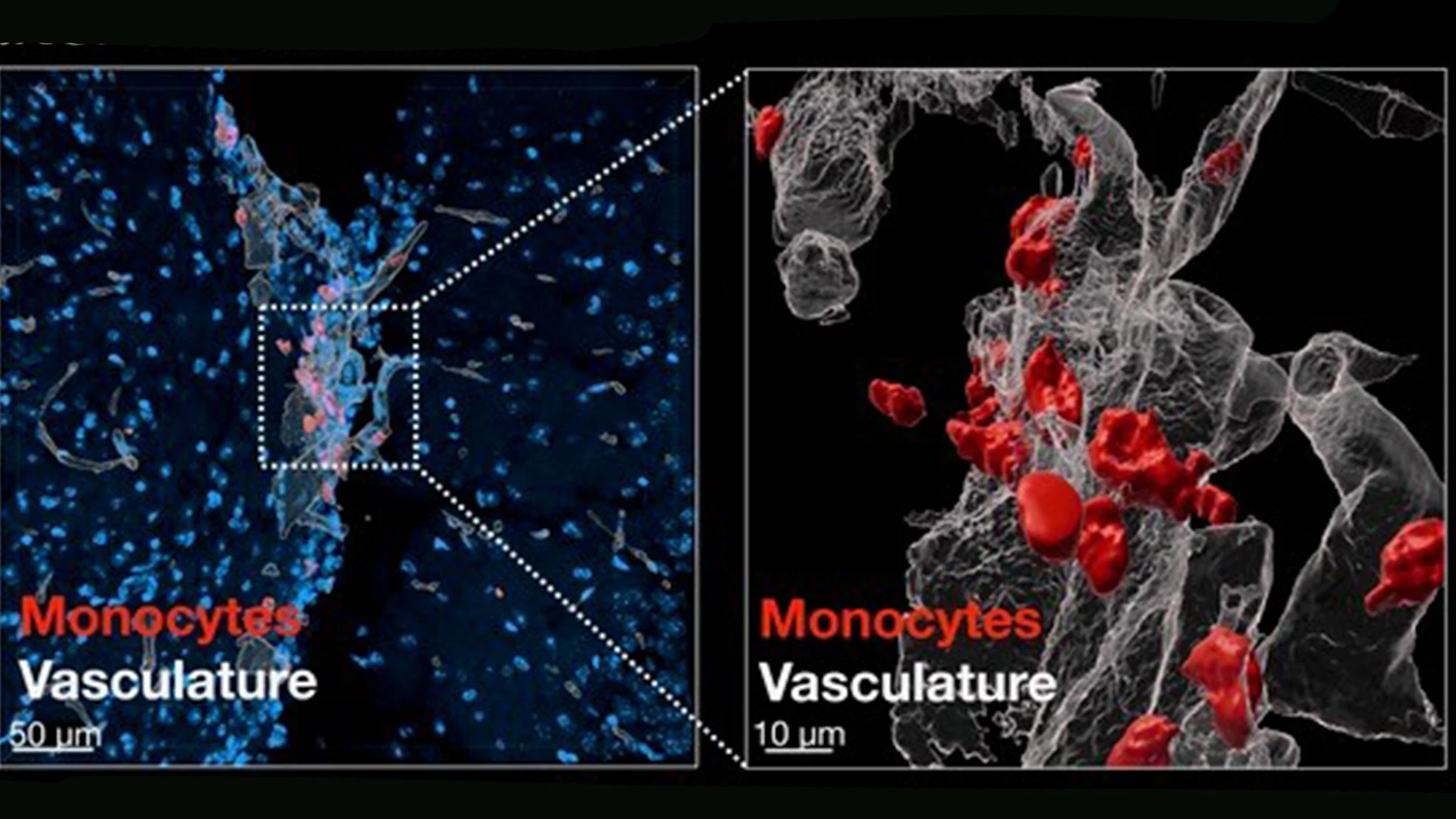

Microscopy images of monocytes in the brain of a mouse after a heart attack.

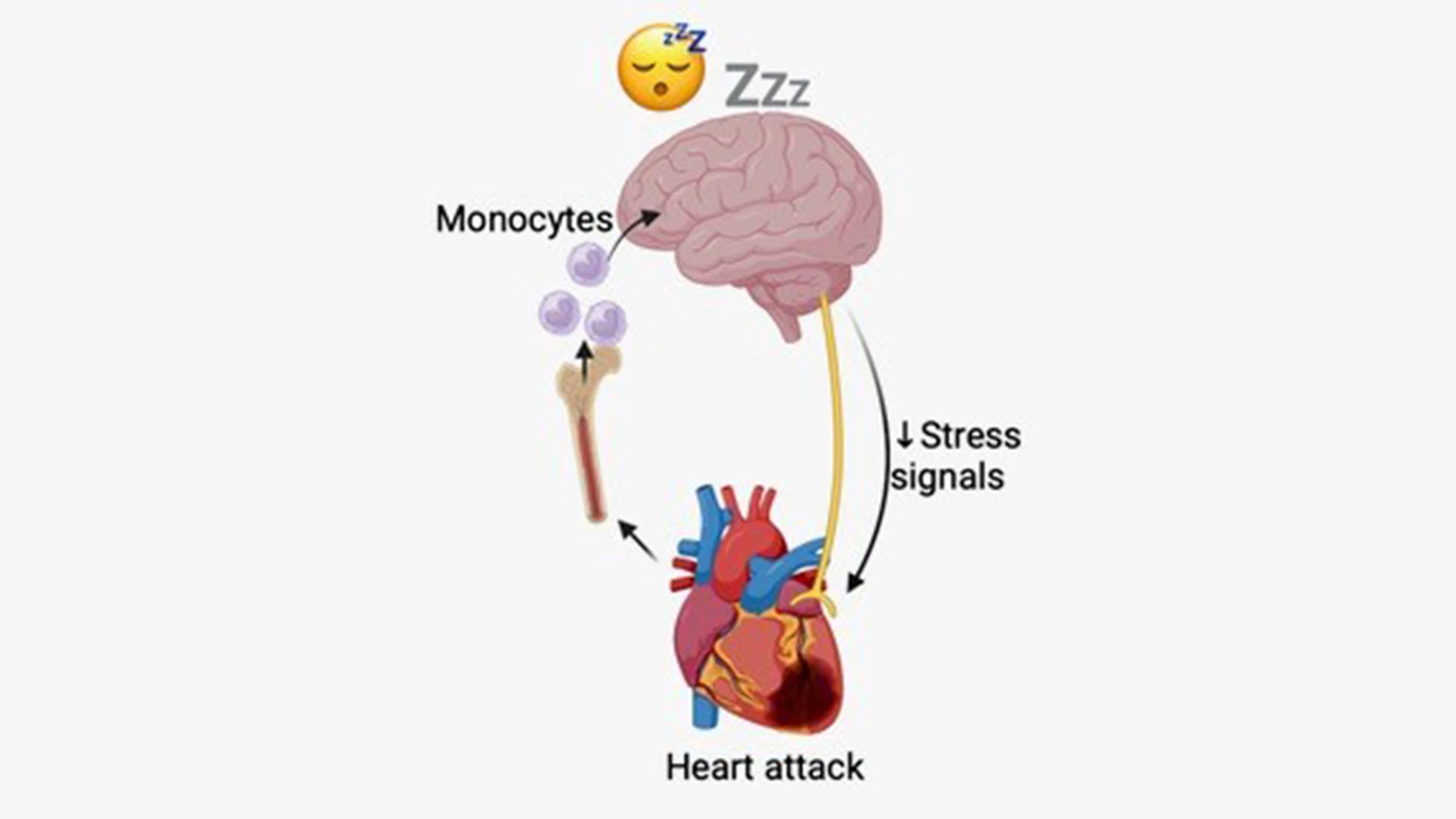

Schematic of hypothesized mechanism: After a heart attack, monocytes are released from the bone marrow and recruited to the brain where they produce TNF to increase sleep, which limits stress signaling to the heart and promotes heart healing and recovery.

To further identify the function of increased sleep after a heart attack, the researchers also interrupted the sleep of some of the mice. The mice with sleep disruption after a heart attack had an increase in heart sympathetic stress responses and inflammation, leading to slower recovery and healing when compared to mice with undisrupted sleep.

The team then turned its attention to humans, and assessed whether healthy sleep in the weeks immediately after acute coronary syndrome (ACS) promoted cardiac healing and recovery. They used the Brief Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (B-PSQI) to assess the sleep quality of 78 patients during the four weeks after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. The team divided the cohort into good sleepers (B-PSQI < 5) and poor sleepers (B-PSQI ≥ 5) post-infarction and conducted two-year follow-up for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).

During the two years following ACS, the incidence of MACE was more than twofold higher and MACE-free survival was significantly lower among patients who slept poorly in the four weeks after their ACS. The team next sought to determine whether sleep quality after ACS influenced functional recovery of the heart. Among those with good sleep, left ventricle ejection fraction improved significantly between baseline (within seven days of ACS) and follow-up (149 ± 52 days post-ACS) visits, while left ventricle ejection fraction did not improve among poor sleepers. “These findings suggest that healthful sleep in the weeks following ACS is an important component of secondary cardiovascular prevention and promotes heart healing and recovery,” suggests Dr. Swirski.

In another human study, the researchers analyzed the impact of five weeks of restricted sleep in 36 healthy adults. Sleep was monitored with a wrist monitor, and the participants kept a sleep diary. During the five-week study period, half the participants slept for the recommended seven to eight hours a night uninterrupted, while the other half restricted their sleep by 1.5 hours each night—either delaying bedtime or waking up early. After the study period, researchers analyzed blood monocytes and found similar sympathetic stress signaling and inflammatory responses in the sleep-restricted group as those that were identified in mice.

“Our study uncovers new ways in which the heart and brain communicate to regulate sleep and supports including sleep as part of the clinical care of patients after a heart attack. Physicians should inform their patients to prioritize restful sleep during cardiac rehabilitation to help the heart heal and recover after a heart attack,” Dr. McAlpine says.

“This study sheds new light on the interconnection between heart disease and sleep,” says Michelle Olive, PhD, Associate Director of the Basic and Early Translational Research Program in the Division of Cardiovascular Sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, part of the National Institutes of Health, which funded this study. “It suggests that more sleep could speed healing after a heart attack and suggests potential pathways for improving cardiac care after these events. Additional studies are needed, particularly clinical studies, to confirm the findings."

This research was supported by the following National Institutes of Health grants: R01HL158534, R00HL151750, R01AG082185, 5T32HL007824-25, P01-HL142494, DP2-CA281401, R01HL128226, R35HL155670, T32HL007343, UL1TR001873.

Featured

Filip K. Swirski, PhD

Director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute, Arthur and Janet C. Ross Professor of Medicine (Cardiology), and Professor of Diagnostic, Molecular, and Interventional Radiology

Cameron McAlpine, PhD

Assistant Professor of Medicine (Cardiology), and Neuroscience