Fasting may be detrimental to fighting off infection, according to a study led by Filip K. Swirski, PhD, Director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. The research, which focused on mouse models, was published in Immunity in February 2023, and could lead to a better understanding of how chronic fasting may affect the body long term.

Specifically, the study said, “We identified a fasting-induced switch in leukocyte migration that prolongs monocyte lifespan and alters susceptibility to disease in mice.”

“There is a growing awareness that fasting is healthful, and there is indeed abundant evidence for the benefits of fasting,” says Dr. Swirski, the Arthur and Janet C. Ross Professor of Medicine, Icahn Mount Sinai. “Our study provides a word of caution as it suggests there may also be a cost to fasting that carries a health risk. This is a mechanistic study delving into some of the fundamental biology relevant to fasting. The study shows that there is a conversation between the nervous and immune systems.”

In the study, researchers analyzed two groups of mice. One group ate breakfast right after waking up (breakfast is their largest meal of the day), and the other group had no breakfast. Researchers collected blood samples in both groups when mice woke up (baseline), then four hours later, and eight hours later. When examining the blood work, researchers saw a difference in the number of monocytes, the white blood cells that are made in the bone marrow and travel through the body, fighting disorders such as infections, heart disease, and cancer.

At baseline, all mice had the same amount of monocytes. But after four hours, monocytes in mice from the fasting group were significantly affected. Researchers found that 90 percent of these cells disappeared from the bloodstream, and the number further declined at eight hours. Meanwhile monocytes in the nonfasting group were unaffected.

“Our study provides a word of caution as it suggests there may also be a cost to fasting that carries a health risk.”

Filip K. Swirski, PhD

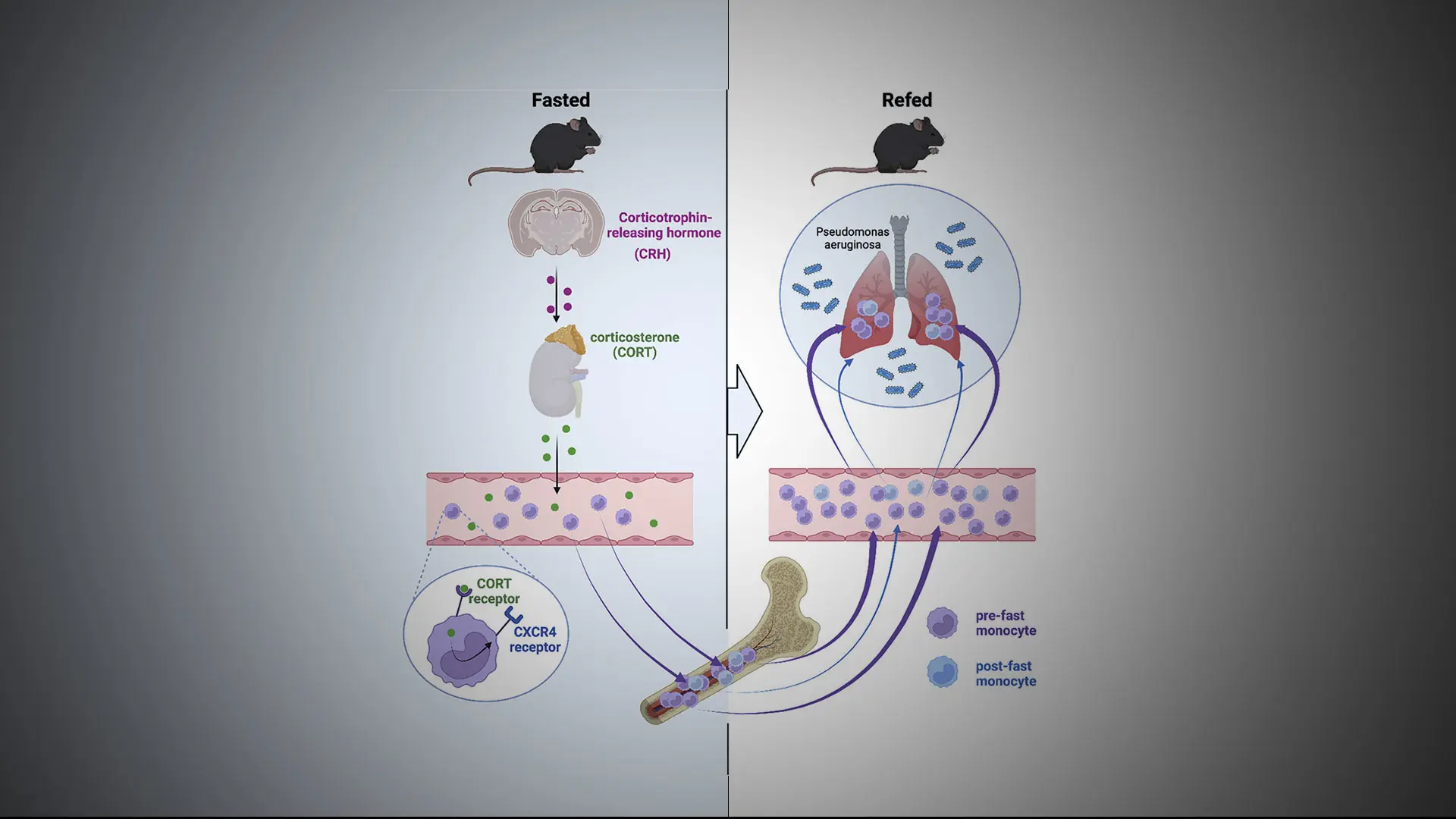

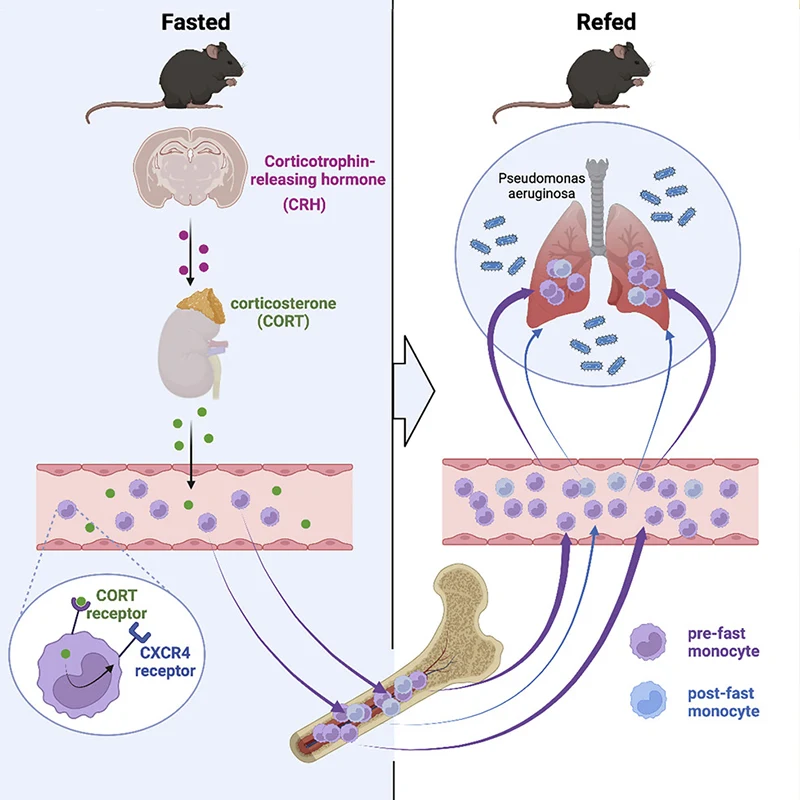

During fasting, a specific region in the brain controls redistribution of monocytes in the blood, with consequences on the response to infection upon refeeding.

In fasting mice, researchers found that the monocytes traveled back to the bone marrow to hibernate. Concurrently, the production of new cells in the bone marrow diminished. The monocytes in the bone marrow—which typically have a short lifespan—survived longer as a consequence of staying in the bone marrow and aged differently than the monocytes that stayed in the blood. The researchers continued to fast mice for up to 24 hours, and then reintroduced food. The cells hiding in the bone marrow surged back into the bloodstream within a few hours.

The study said, “Monocyte re-entry was orchestrated by hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis-dependent release of corticosterone, which augmented the CXCR4 chemokine receptor. Although the marrow is a safe haven for monocytes during nutrient scarcity, refeeding prompted mobilization, culminating in monocytosis of chronologically older and transcriptionally distinct monocytes.”

In other words, the surge led to a heightened level of inflammation. Instead of protecting against infection, these altered monocytes were more inflammatory, making the body less resistant to fighting infection.

This study is among the first to make the connection between the brain and these immune cells during fasting, Dr. Swirski says. Researchers found that specific regions in the brain controlled the monocyte response during fasting. This study demonstrated that fasting elicits a stress response in the brain, and this instantly triggers a large-scale migration of these white blood cells from the blood to the bone marrow, and then back to the bloodstream shortly after food is reintroduced.

Dr. Swirski emphasized that, while there is also evidence of the metabolic benefits of fasting, the study is a useful advance in the full understanding of the body’s mechanisms.

“The study shows that, on the one hand, fasting reduces the number of circulating monocytes, which one might think is a good thing, as these cells are important components of inflammation. On the other hand, reintroduction of food creates a surge of monocytes flooding back to the blood, which can be problematic. Fasting, therefore, regulates this pool in ways that are not always beneficial to the body’s capacity to respond to a challenge such as an infection,” explains Dr. Swirski. “Because these cells are so important to other diseases such as heart disease or cancer, understanding how their function is controlled is critical.”

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Cure Alzheimer’s Fund.

Featured

Filip K. Swirski, PhD

Director of the Cardiovascular Research Institute, Arthur and Janet C. Ross Professor of Medicine (Cardiology), and Professor of Diagnostic, Molecular, and Interventional Radiology

Cameron McAlpine, PhD

Assistant Professor of Medicine (Cardiology), and Neuroscience