Patients identified by nuclear stress testing as having severe stress-induced myocardial ischemia are likely to benefit from heart bypass surgery or angioplasty, while those with mild or no ischemia are not, according to a new study led by Alan Rozanski, MD, Professor of Medicine (Cardiology), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

For patients in the study with severe ischemia, early revascularization was associated with a more than 30 percent reduction in mortality compared to patients with severe ischemia who were treated with medication, but no benefit was shown for the other groups.

The research, published in June 2022 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, is the first large-scale study to look at the impact of stress testing on patient management when applied to the full spectrum of patients who have both varying degrees of myocardial ischemia and heart function. This new study can help guide physicians on how to manage caring for patients with suspected heart disease.

“There is keen interest in assessing how measurement of myocardial ischemia during stress testing can help shape physicians’ decisions to refer patients for coronary revascularization procedures, but this issue has not been well studied among patients who have underlying heart damage,” says Dr. Rozanski, Director of Nuclear Cardiology and Cardiac Stress Testing and Chief Academic Officer for the Department of Cardiology at Mount Sinai Morningside. “Our study, which evaluated a large number of patients with pre-existing heart damage who underwent cardiac stress testing, finally addresses this clinical void.”

The researchers analyzed records of more than 43,000 patients who underwent nuclear stress testing with suspected CAD between 1998 and 2017 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles with a median 11-year follow-up for mortality/survival. The investigators grouped patients according to both their level of myocardial ischemia during stress testing as well as their left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), which measures the percent of blood volume pumped out of the heart’s main chamber during each heartbeat. Low LVEF measurements indicate prior heart damage that could be from scarring of the heart due to a prior heart attack.

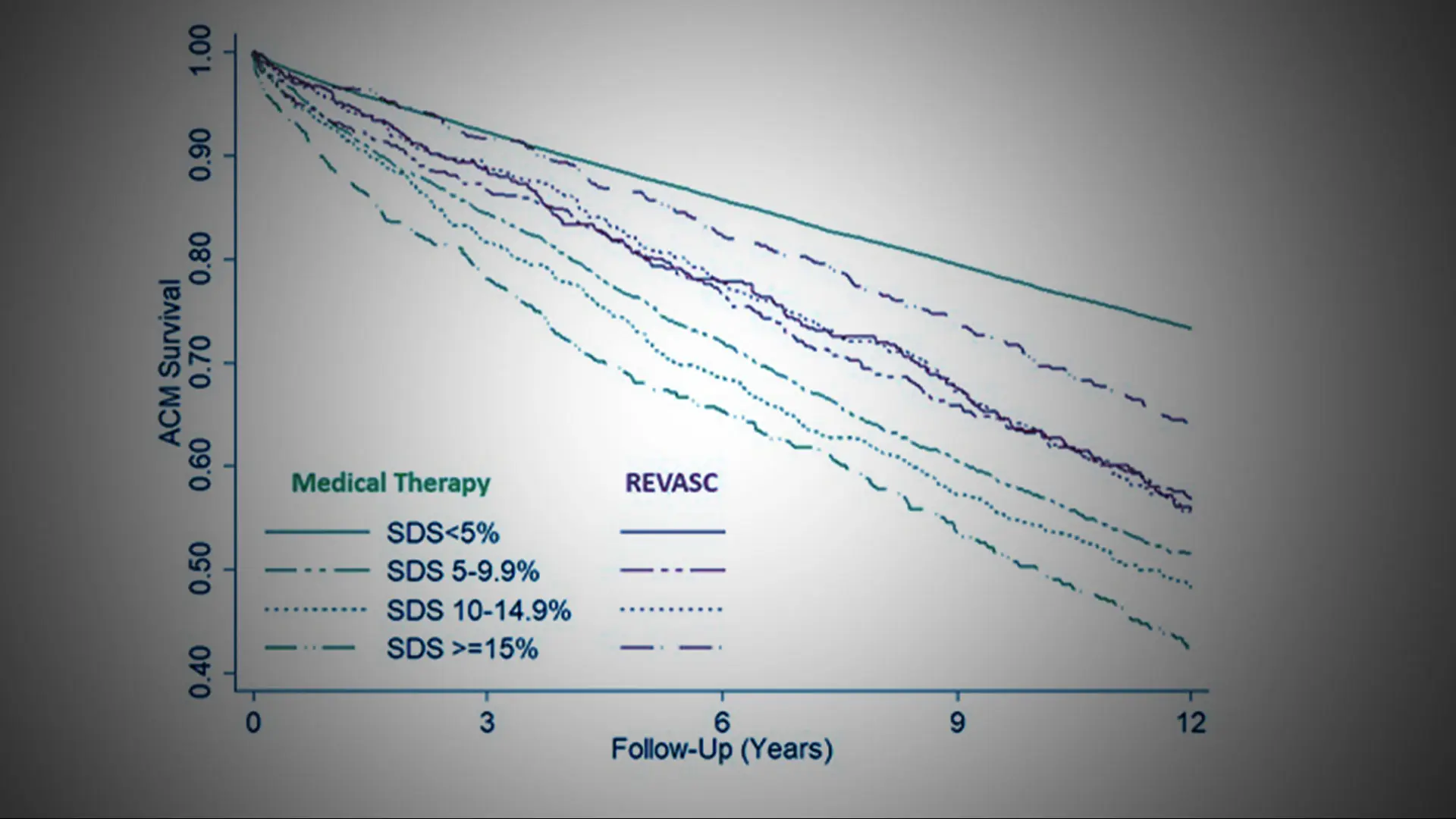

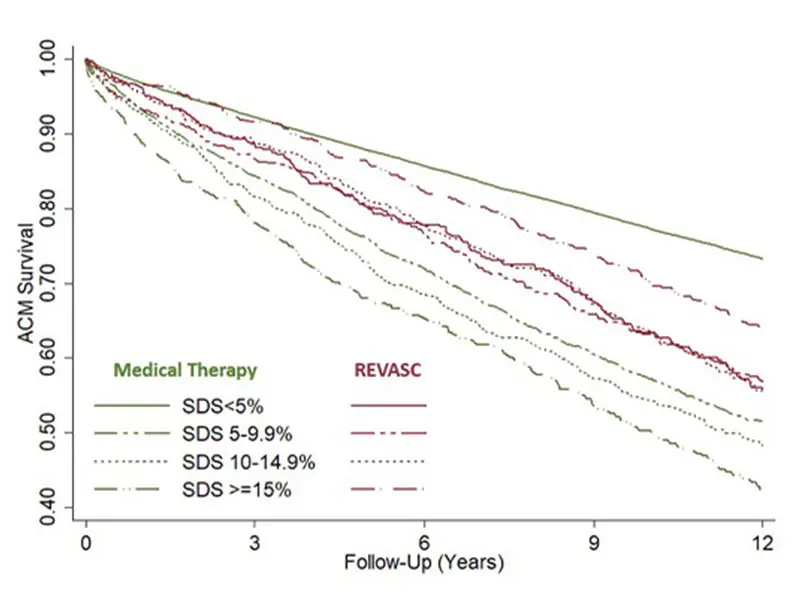

Survival according to the magnitude of inducible ischemia and early revascularization status.

The study provided two important clinical insights. First, it showed that the frequency of myocardial ischemia during stress testing varied according to patients’ heart function. Of the 39,883 patients with normal heart function (LVEF above 55 percent), fewer than 8 percent of them had ischemia. However, among the 3,560 patients with reduced heart function (LVEF less than 45 percent), more than 40 percent had myocardial ischemia.

The study also showed that the presence of myocardial ischemia increases the risk of death in patients with normal and reduced heart function. Among both groups of patients, performing bypass or PCI procedures was not associated with improved survival among the large percentage of patients who had either no or only mild ischemia during the cardiac stress test. Among patients with severe ischemia, coronary procedures were associated with more than 30 percent higher survival rates compared to those managed with medication only. This was the case for patients with and without heart damage.

“These results confirm the benefits of stress testing for clinical management. What you want from any test when considering coronary revascularization procedures is that the test will identify a large percentage of patients who are at low clinical risk and do so correctly, while identifying only a small percentage of patients who are at high clinical risk and do so correctly. That is what we found with nuclear stress testing in this study,” Dr. Rozanski says. “Importantly, the presence of severe ischemia does not necessarily mean that coronary revascularization should be applied. New data from a large clinical trial suggests that when medical therapy is optimized, it may be as effective as coronary revascularization in such patients. Regardless, the presence of severe ischemia indicates high clinical risk, which then requires aggressive management to reduce clinical risk.”

Featured

Alan Rozanski, MD

Professor of Medicine (Cardiology)