The Center for Inherited Cardiovascular Diseases (CICVD) was established in 2022 by Mount Sinai Heart to implement and advance genomic approaches to improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cardiovascular disease. The Center positions Mount Sinai at the forefront of cardiovascular genomic medicine.

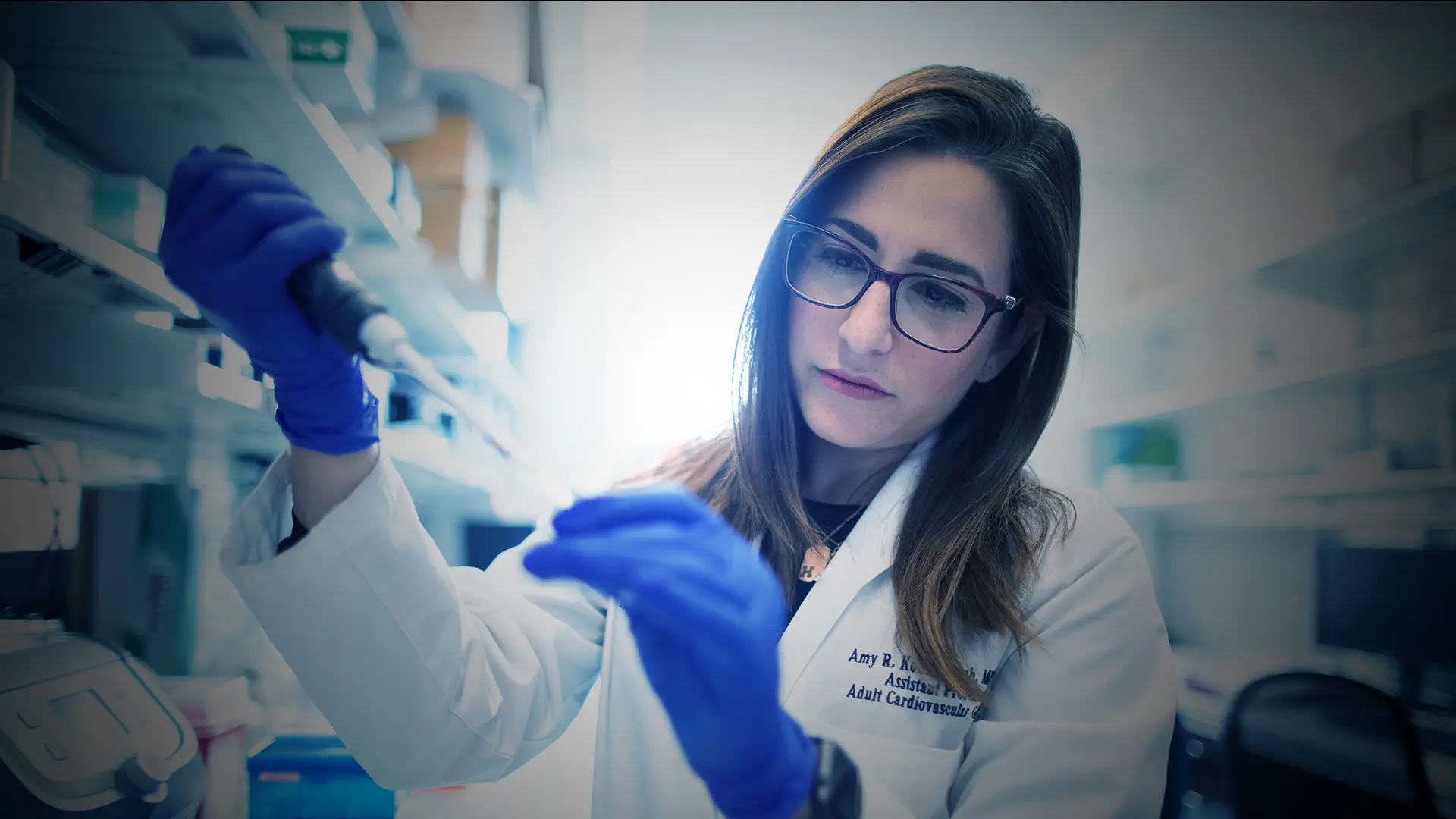

Traditionally, cardiovascular care follows a path from symptom to testing to treatment. But cardiovascular genetics tends to be more conversational and bidirectional, says Amy Kontorovich, MD, PhD, founding Director of the Center, and Associate Professor of Medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. “This process requires spending a lot of time talking to patients about their family history, counseling them about genetic testing, and then discussing the interpretation of the results and what it means for their health. The current structure of day-to-day routine clinical practice does not support those processes,” Dr. Kontorovich says.

“The CICVD was born out of an observed need for more resources to support cardiologists and other specialists in identifying who would benefit from a cardiovascular genetics assessment, enacting that assessment, and supporting the providers and patients at multiple steps along the way,” she adds.

Patients have taken several paths to reach the CICVD. Some are seeking more information after taking a direct-to-consumer genetic test that showed they are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. “Previously, there was no hub where someone could get answers to those questions,” Dr. Kontorovich says. More often, patients are referred to the Center because they have a family history of cardiovascular condition, such as cardiomyopathy, that may be related to an underlying genetic mutation. Once they come to the Center, providers help them complete a detailed family history and discuss which genetic tests might be appropriate. “Our genetic counselor provides in-depth counseling about what the testing means, including preparing individuals for the possibility of ambiguous results.”

Amy Kontorovich, MD, PhD, founding Director of the Center, left, with genetic counselor Veronica Fettig.

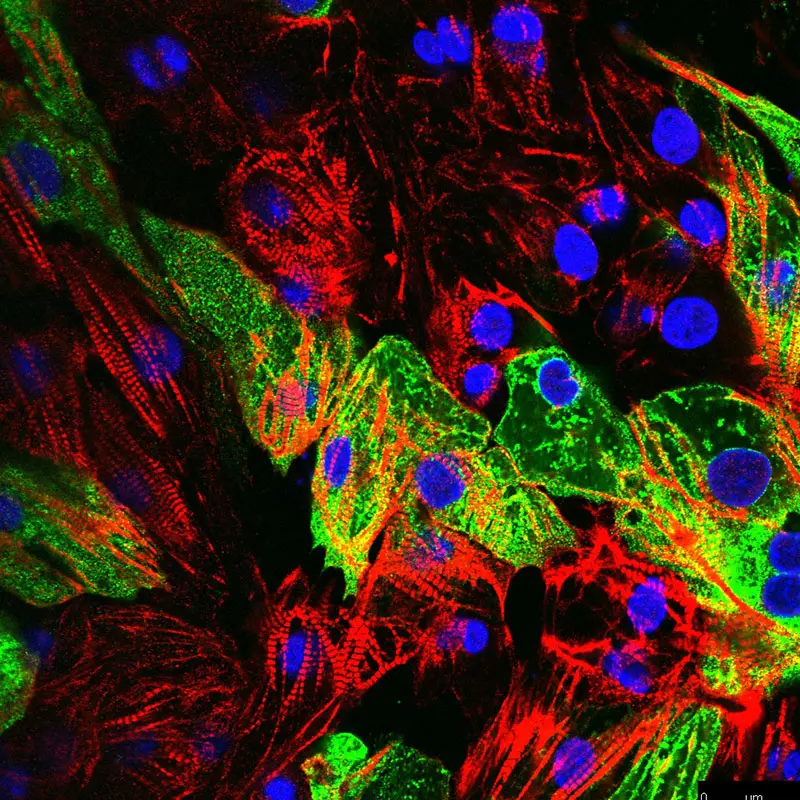

Dr. Kontorovich is also investigating the role of human genetics in cardiac susceptibility to myocarditis after exposure to the COVID-19 virus. Above, the viral uptake in heart cells 48 hours after infection is shown in green.

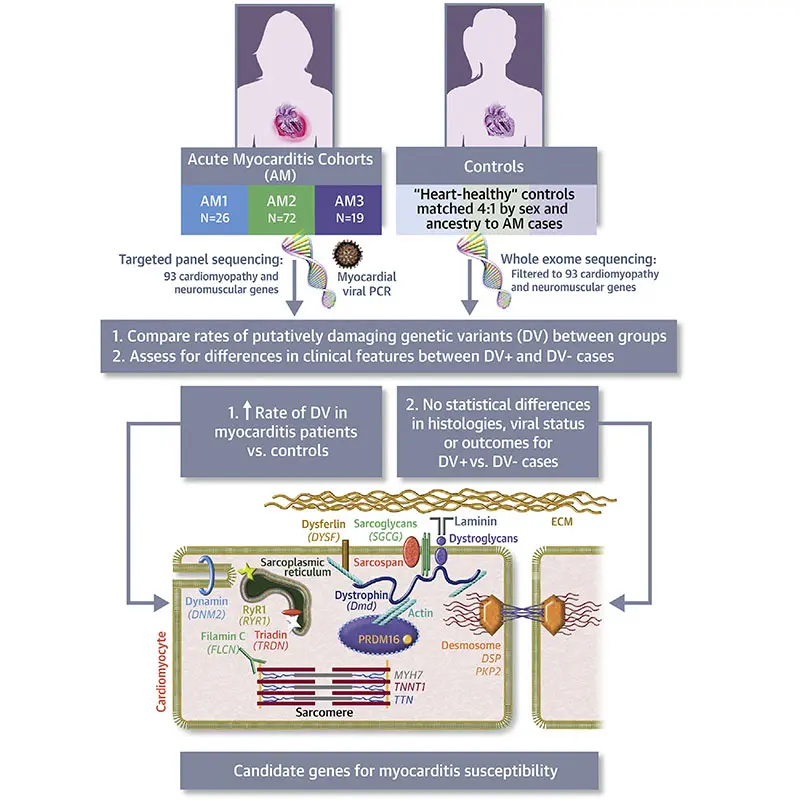

Virtual abstract of the article "Myopathic Cardiac Genotypes Increase Risk for Myocarditis" in JACC.

Several cardiovascular conditions are associated with genetic causes, and patients with such conditions, including cardiomyopathies, certain arrhythmia disorders and channelopathies, aortopathies, and arteriopathies, may benefit from a genetic evaluation. Dr. Kontorovich and her colleagues frequently see patients with familial hypercholesterolemia, which is thought to occur in 1 of every 250 to 500 people. They also see patients with hereditary transthyretin amyloid (hATTR) cardiomyopathy, which can be associated with a genetic trait present in 1 of every 25 individuals of African American descent and likely overrepresented in people of Caribbean and Hispanic ancestry, as well, she notes. “Among the population we treat in New York City, TTR amyloidosis is not uncommon. But it is underrecognized and underdiagnosed.” Dr. Kontorovich emphasizes that uncovering a diagnosis of hATTR through genetic testing can be very impactful, as this opens up new therapeutic options for patients that may modify the course of their disease.

The CICVD is also engaged in research, including work to explore the genetics of myocarditis, the natural history of hATTR, and high-risk markers for aortopathy. The Center is also poised to conduct clinical trials for genetic cardiovascular diseases. “I envision the CICVD will lead personalized trials for genotype-directed therapies,” Dr. Kontorovich says.

In her own research, Dr. Kontorovich led a study that associated increased risk for myocarditis with specific human genetic mutations. In this study, published in July 2021 in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, researchers performed targeted genomic sequencing in 117 people with myocarditis across a range of etiologies, predominantly viral and idiopathic, and compared to 468 matched controls without myocarditis. Putatively damaging variants in genes related to cardiomyocyte structure and function were found in 16 percent of individuals with myocarditis, significantly enriched against controls.

“We therefore confirmed in the largest cohort to date that impairments in structural cardiomyocyte genes attribute risk in myocarditis,” Dr. Kontorovich says. “This represents a paradigm shift in the understanding of this disease and opens up new pathways for diagnostics, prophylactic measures, and future treatments.”

Looking ahead, she and her colleagues hope to establish a program for postmortem molecular autopsies to collect genetic information that may be beneficial for family members when a patient dies from a condition that may have a genetic component. “If a condition is hereditary, and surviving relatives may be at risk, we can work with the medical examiner or coroner’s office to perform genetic testing and make family members aware of their risk,” she says. “We are working on optimizing these processes to do this more often, for more people, in a more equitable way.”

Another goal for the Center is to help providers make informed decisions within the emerging field of polygenic risk scores. “We think of most genetic cardiovascular disease as monogenic— one high-impact change in a gene causes disease. But big genome-wide association studies have determined that multiple low-impact changes, in aggregate, may increase a person’s risk of cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Kontorovich says. “These polygenic risk scores will be available soon in clinical practice, but no one is yet trained to deal with them. We hope to support cardiologists and other specialists in how to interpret and implement this information.”